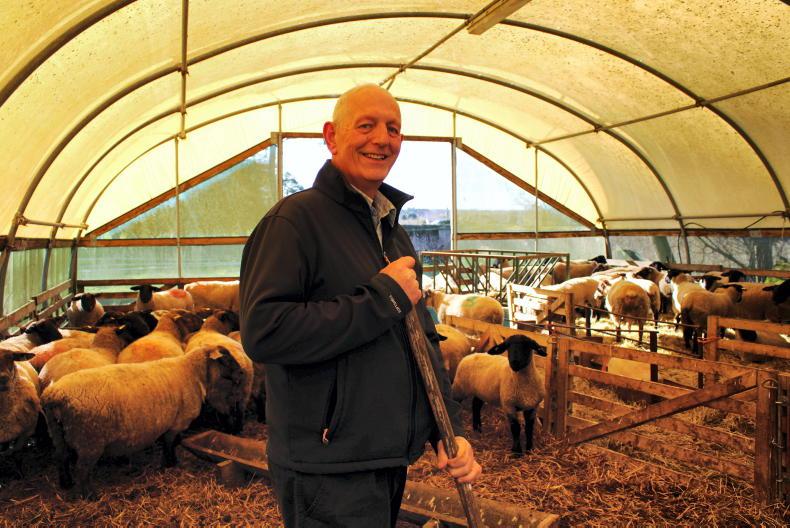

Kildare sheep and cattle farmer Pádraig Murphy photographed on the family farm. \ Valerie Murphy

My phone rang at midnight. “We may have a match.”

The liver co-ordinator’s voice was calm and direct. My heart, by contrast, began to beat rapidly.

She gave me the news we had been praying for since my husband was put on the liver transplant list some six months previously.

What was I doing at that particular moment when the call came through? Defrosting my freezer.

The tension in our house was so high that I couldn’t sleep properly and sought out any distraction that might help me cope with the urgency of the situation.

Valerie and Pádraig Murphy, pictured before Pádraig's illness

My husband, however, was sleeping constantly – he was exhausted from carrying up to 20kg of abdominal fluid at a time – followed by long hospital stays for diuretics and a variety of procedures.

His M.E.L.D score (measure of end liver disease) was sky-rocketing; platelets were low and his kidneys were under severe pressure.

Here was a man who 18 months previously had been going about a normal day’s work in the Department of Agriculture, followed by checking sheep and cattle on the family farm.

Some years earlier, he had been diagnosed with haemochromatosis and accepted the numerous trips to hospital for venesection with quiet resignation.

However, in the summer months of 2018, there was an obvious change in his condition. His weight and joint pain began to increase although his face became gaunt. The tell-tale jaundice in his eyes started the rumour mill in our locality.

One day, in desperation, I rang Margaret Mullet from the Irish Haemochromatosis Society. An article about this medical condition in Irish Country Living that week had been both informative and alarming.

It was so comforting to speak with someone who understood my fears.

She stopped me midway through our conversation and gently chided me: “As you are well capable of explaining his symptoms, Valerie, put the phone down right now and ring the consultant again. Demand that every point you’ve raised is answered. Start fighting for your husband before it’s too late.”

This was the impetus I needed. The kitchen table was covered with hastily written “post-its” full of my observations and amateur research. There must have been a steely resolve evident in my voice because I got a swift response.

We were asked to meet the consultant without delay. One look at my husband’s swollen abdomen and he was quickly admitted. A series of tests were carried out including an endoscopy.

As I waited outside the theatre afterwards, I could hear his cross voice wafting down the corridor, “We are not cancelling our holidays! I’m fine.”

As the trolley came into view, a nurse shook her head vigorously. “He won’t be going anywhere,” she whispered.

On the transplant list

How right she was, for the following year our lives were centred around hospital admissions and trying to grasp complex terminology.

The liver co-ordinators in St Vincent’s University Hospital kept us informed of where my husband was on the fateful timeline.

With every visit we hoped that he was one step closer to making the transplant list – yet, conversely, that meant his condition was deteriorating.

It’s not a decision the medical team take lightly; the only way I can explain it is to call it the “see-saw effect”. They monitor the patient’s condition carefully and try to stabilise it with a variety of appropriate drugs.

However, when the stage is reached at which one’s quality of life without a transplant will be seriously impeded, then they move swiftly to find a match.

St Vincent’s became our second home and the echo of our footsteps on the long trek up to St Brigid’s Ward will ring in our ears forever.

After only two weeks on the list, we got a call one evening to say that a potential match had been offered. We were told not to panic- that as a series of checks would have to be performed, time was on our side.

On arrival, the whole procedure was patiently explained to us, questions were answered in detail and papers were signed. I was told to return in the early morning before the operation would begin.

Luckily, my aunt lived nearby and I headed to her house to rest. It was so comforting to be given a warm hug and sit and chat through all my worries.

Afterwards, my hazy sleep was broken at about 4am. I was informed that the donor organ was not suitable and that my husband was free to go home.

For a few minutes I was paralysed with disappointment. I then remembered how many people we had rung on our journey up who would have to be informed that the operation was not going ahead.

We resolved not to call anyone until he was actually in theatre if he got a second chance in the future.

Some six months later, that opportunity materialised. We were calmer this time and drove along quiet roads on a balmy night.

After a number of blood tests were taken, my husband fell asleep. By this stage he was so weary, I was glad to see him rest before the operation.

I paced the floor staring out the window at the Poolbeg chimneys as the inky night turned to a pale grey morning and Dubliners roused themselves to face another day.

The door swung open and a nurse smiled and said, “It’s going ahead.”

Hope and gratitude

People have asked me how we felt as we headed down for the transplant that morning. I can honestly say there was nothing in our hearts but hope and gratitude because we knew there was no alternative.

I was well briefed and reassured at various stages during the operation and visited him in ICU later that evening. When he was awoken the following day, he motioned to us immediately that he wanted to write something.

A nurse returned with a pen and notebook and he scrawled, “Thank you”. My daughter and I smiled at each other. Then he added, “To the family”. Better again! By this time his nurse was reading the message along with us. Then he became agitated as if he had something else to add: “……. of the donor.”

He slumped back on his pillow, exhausted with the effort. It was a very emotional moment; an acknowledgement of the gift of life, for which we will be eternally grateful.

Each day in recovery spelled progress. We celebrated the removal of every tube and he worked closely with the physiotherapist as he learned to strengthen his muscles and become mobile again.

Once he got his phone back, he was able to chat with all the friends who had been so supportive during his illness and get a feel for the world outside hospital walls.

No-one confirmed his obvious return to normal health as much as our youngest son who bounded into the ward on his return from holidays in Mexico.

Luckily for him, he had escaped all the trauma. He took one look at his dad and grinned, “Ah, lads, what was all the fuss about? You look fine!”

Arriving home with a boxload of medication was not as daunting as it might seem. Once again, the liver co-ordinators had been firm in their instruction that managing his drug regime was his responsibility, not mine.

It has continued thus and every appointment since has recorded a reduction in his intake. Two years on and he is going about his daily life with few restrictions.

Kildare farmer and liver transplant recipient Pádraig Murphy pictured with his pedigree Suffolk ewes. \ Valerie Murphy

Not a day passes, however, without a reference to the donor who gave him this new chance of life. A candle is lit and placed in the centre of our Christmas table each year to keep his memory uppermost in our minds.

Although my husband couldn’t participate fully in the lambing last season, I observed his silent joy as he watched the new-born lambs frolic and grow sturdy in the fields.

There will be occasional obstacles on his journey to full recovery but for now- life is good and precious.

Note: The fee for this feature has been kindly donated by Valerie Murphy to the Friends of St. Vincent’s University Hospital in recognition of their dedicated work.

Read more

Why resilience is important

‘Her presence is my present‘

Kildare sheep and cattle farmer Pádraig Murphy photographed on the family farm. \ Valerie Murphy

My phone rang at midnight. “We may have a match.”

The liver co-ordinator’s voice was calm and direct. My heart, by contrast, began to beat rapidly.

She gave me the news we had been praying for since my husband was put on the liver transplant list some six months previously.

What was I doing at that particular moment when the call came through? Defrosting my freezer.

The tension in our house was so high that I couldn’t sleep properly and sought out any distraction that might help me cope with the urgency of the situation.

Valerie and Pádraig Murphy, pictured before Pádraig's illness

My husband, however, was sleeping constantly – he was exhausted from carrying up to 20kg of abdominal fluid at a time – followed by long hospital stays for diuretics and a variety of procedures.

His M.E.L.D score (measure of end liver disease) was sky-rocketing; platelets were low and his kidneys were under severe pressure.

Here was a man who 18 months previously had been going about a normal day’s work in the Department of Agriculture, followed by checking sheep and cattle on the family farm.

Some years earlier, he had been diagnosed with haemochromatosis and accepted the numerous trips to hospital for venesection with quiet resignation.

However, in the summer months of 2018, there was an obvious change in his condition. His weight and joint pain began to increase although his face became gaunt. The tell-tale jaundice in his eyes started the rumour mill in our locality.

One day, in desperation, I rang Margaret Mullet from the Irish Haemochromatosis Society. An article about this medical condition in Irish Country Living that week had been both informative and alarming.

It was so comforting to speak with someone who understood my fears.

She stopped me midway through our conversation and gently chided me: “As you are well capable of explaining his symptoms, Valerie, put the phone down right now and ring the consultant again. Demand that every point you’ve raised is answered. Start fighting for your husband before it’s too late.”

This was the impetus I needed. The kitchen table was covered with hastily written “post-its” full of my observations and amateur research. There must have been a steely resolve evident in my voice because I got a swift response.

We were asked to meet the consultant without delay. One look at my husband’s swollen abdomen and he was quickly admitted. A series of tests were carried out including an endoscopy.

As I waited outside the theatre afterwards, I could hear his cross voice wafting down the corridor, “We are not cancelling our holidays! I’m fine.”

As the trolley came into view, a nurse shook her head vigorously. “He won’t be going anywhere,” she whispered.

On the transplant list

How right she was, for the following year our lives were centred around hospital admissions and trying to grasp complex terminology.

The liver co-ordinators in St Vincent’s University Hospital kept us informed of where my husband was on the fateful timeline.

With every visit we hoped that he was one step closer to making the transplant list – yet, conversely, that meant his condition was deteriorating.

It’s not a decision the medical team take lightly; the only way I can explain it is to call it the “see-saw effect”. They monitor the patient’s condition carefully and try to stabilise it with a variety of appropriate drugs.

However, when the stage is reached at which one’s quality of life without a transplant will be seriously impeded, then they move swiftly to find a match.

St Vincent’s became our second home and the echo of our footsteps on the long trek up to St Brigid’s Ward will ring in our ears forever.

After only two weeks on the list, we got a call one evening to say that a potential match had been offered. We were told not to panic- that as a series of checks would have to be performed, time was on our side.

On arrival, the whole procedure was patiently explained to us, questions were answered in detail and papers were signed. I was told to return in the early morning before the operation would begin.

Luckily, my aunt lived nearby and I headed to her house to rest. It was so comforting to be given a warm hug and sit and chat through all my worries.

Afterwards, my hazy sleep was broken at about 4am. I was informed that the donor organ was not suitable and that my husband was free to go home.

For a few minutes I was paralysed with disappointment. I then remembered how many people we had rung on our journey up who would have to be informed that the operation was not going ahead.

We resolved not to call anyone until he was actually in theatre if he got a second chance in the future.

Some six months later, that opportunity materialised. We were calmer this time and drove along quiet roads on a balmy night.

After a number of blood tests were taken, my husband fell asleep. By this stage he was so weary, I was glad to see him rest before the operation.

I paced the floor staring out the window at the Poolbeg chimneys as the inky night turned to a pale grey morning and Dubliners roused themselves to face another day.

The door swung open and a nurse smiled and said, “It’s going ahead.”

Hope and gratitude

People have asked me how we felt as we headed down for the transplant that morning. I can honestly say there was nothing in our hearts but hope and gratitude because we knew there was no alternative.

I was well briefed and reassured at various stages during the operation and visited him in ICU later that evening. When he was awoken the following day, he motioned to us immediately that he wanted to write something.

A nurse returned with a pen and notebook and he scrawled, “Thank you”. My daughter and I smiled at each other. Then he added, “To the family”. Better again! By this time his nurse was reading the message along with us. Then he became agitated as if he had something else to add: “……. of the donor.”

He slumped back on his pillow, exhausted with the effort. It was a very emotional moment; an acknowledgement of the gift of life, for which we will be eternally grateful.

Each day in recovery spelled progress. We celebrated the removal of every tube and he worked closely with the physiotherapist as he learned to strengthen his muscles and become mobile again.

Once he got his phone back, he was able to chat with all the friends who had been so supportive during his illness and get a feel for the world outside hospital walls.

No-one confirmed his obvious return to normal health as much as our youngest son who bounded into the ward on his return from holidays in Mexico.

Luckily for him, he had escaped all the trauma. He took one look at his dad and grinned, “Ah, lads, what was all the fuss about? You look fine!”

Arriving home with a boxload of medication was not as daunting as it might seem. Once again, the liver co-ordinators had been firm in their instruction that managing his drug regime was his responsibility, not mine.

It has continued thus and every appointment since has recorded a reduction in his intake. Two years on and he is going about his daily life with few restrictions.

Kildare farmer and liver transplant recipient Pádraig Murphy pictured with his pedigree Suffolk ewes. \ Valerie Murphy

Not a day passes, however, without a reference to the donor who gave him this new chance of life. A candle is lit and placed in the centre of our Christmas table each year to keep his memory uppermost in our minds.

Although my husband couldn’t participate fully in the lambing last season, I observed his silent joy as he watched the new-born lambs frolic and grow sturdy in the fields.

There will be occasional obstacles on his journey to full recovery but for now- life is good and precious.

Note: The fee for this feature has been kindly donated by Valerie Murphy to the Friends of St. Vincent’s University Hospital in recognition of their dedicated work.

Read more

Why resilience is important

‘Her presence is my present‘

SHARING OPTIONS