When Professor Luke O’Neill was working as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, he was playing guitar in a band called The Sleeping Arrangements.

They played a lot of pub gigs and at one stage were offered an elusive tour of Europe.

Despite some of his bandmates really wanting to pursue the opportunity, Luke declined. There was another area of his life going very well and he wanted to focus on that.

“Of course some of the guys, they weren’t impressed, ‘We wanted to go and you said no’. I said no because I had just made a big discovery in the lab.

“I realised if I leave that now, that’s a missed opportunity. If I said yes, I may never have come back,” Luke muses with a laugh.

Now a world-renowned professor of biochemistry and immunology at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), music’s loss was certainly science’s gain. Luke’s not out of the gigging scene completely though, but more on that later.

As well as researching medicines to treat COVID-19 with his team, throughout the pandemic Luke has been to the forefront of communicating scientific messages to the public in the media.

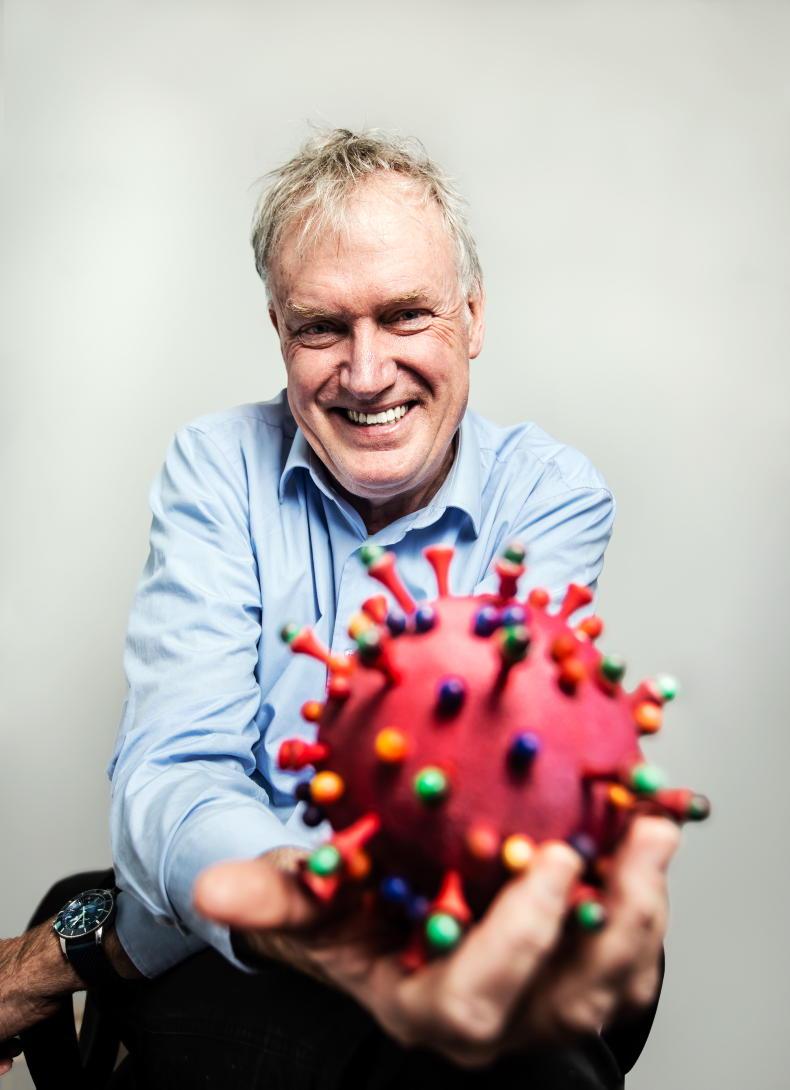

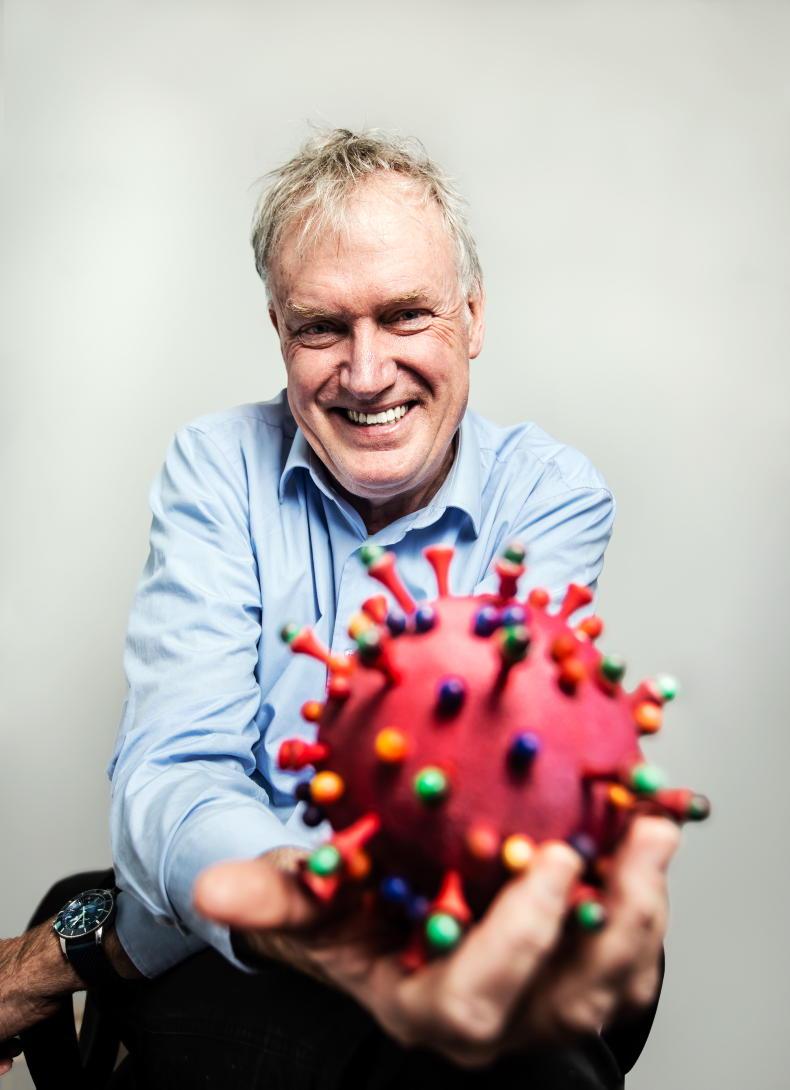

Luke O'Neill is an immunologist at Trinity College Dublin. \ Philip Doyle

His ability to make science accessible to the masses has seen his popularity sore in the current climate.

However, it’s important to note this is not a new venture for Luke. Distilling science to make it understandable has been a long-term mission of his. For him, it’s about getting people to understand the science behind things. If some people are encouraged to pursue science as a career, even better.

We meet Luke at the Trinity Biomedical Sciences Institute for a socially distanced chat. Luke, if you have heard him on TV or radio before, is just as you would expect him to be, extremely positive!

In fact, meeting him, it’s very easy to see why he’s so in demand at the minute. His mood is infectious. The ‘COVID gloom cloud’ disperses when you’re around him. Not in the sense that it’s ignored, but the whole thing feels more manageable. After speaking with him, you feel happy and hopeful, rejuvenated by his presence.

Luke’s positive outlook, he believes, is both somewhat innate and moulded by his profession.

“I think it’s partly my disposition, we’re all a bit different, aren’t we? But also to be a scientist, you have to be optimistic. The reason is: your experiments are usually failing, because your idea is wrong, you can’t prove it or the machine breaks down. You get back up on the horse again,” he explains.

“The most successful scientists have the capacity to bounce back from stuff not working out. If science was easy, we would have discovered a cure for cancer, remember. It’s very difficult, so you have to have that sense of hope, that if I have a new idea or I change my idea – it’s trial and error –I’ll go again. I suspect that’s where the optimism comes from.

“With this one (COVID-19), I knew from the very start science would beat it. I could say that because I know all the scientists, I know all the companies, I know they’re working very hard. The brightest and best people in the world are trying to get a vaccine treatment and I knew they’d win.”

Even though we may still be in the thick of the pandemic at present, Luke says there’s absolutely reason to be hopeful. Vaccines are coming fast, alongside very positive signs from countries like Israel, who are far more advanced in their vaccine rollout. All of the vaccines, including AstraZeneca, will prevent you getting sick and ending up in hospital.

Farm boosts immunity

On the subject of vaccines, Luke has a tit-bit of information for Irish Country Living readers specifically. The first vaccine was invented by a farmer, well sort of!

It was a well-known folktale during the smallpox outbreak that milk maids were often immune to the disease, this turned out to be due to their exposure to cowpox. The first successful vaccine trial is attributed to Edward Jenner, a medical doctor. But a farmer that lived close to him, Benjamin Jesty, claimed he was the first to discover injecting someone with cowpox could prevent smallpox.

Edward Jenner received widespread recognition; money from the UK government, Napoleon commended him and the empress of Russia sent him a diamond. Benjamin Jesty contacted the houses of parliament saying he wanted recognition. He was given a special gift of a gold lancet.

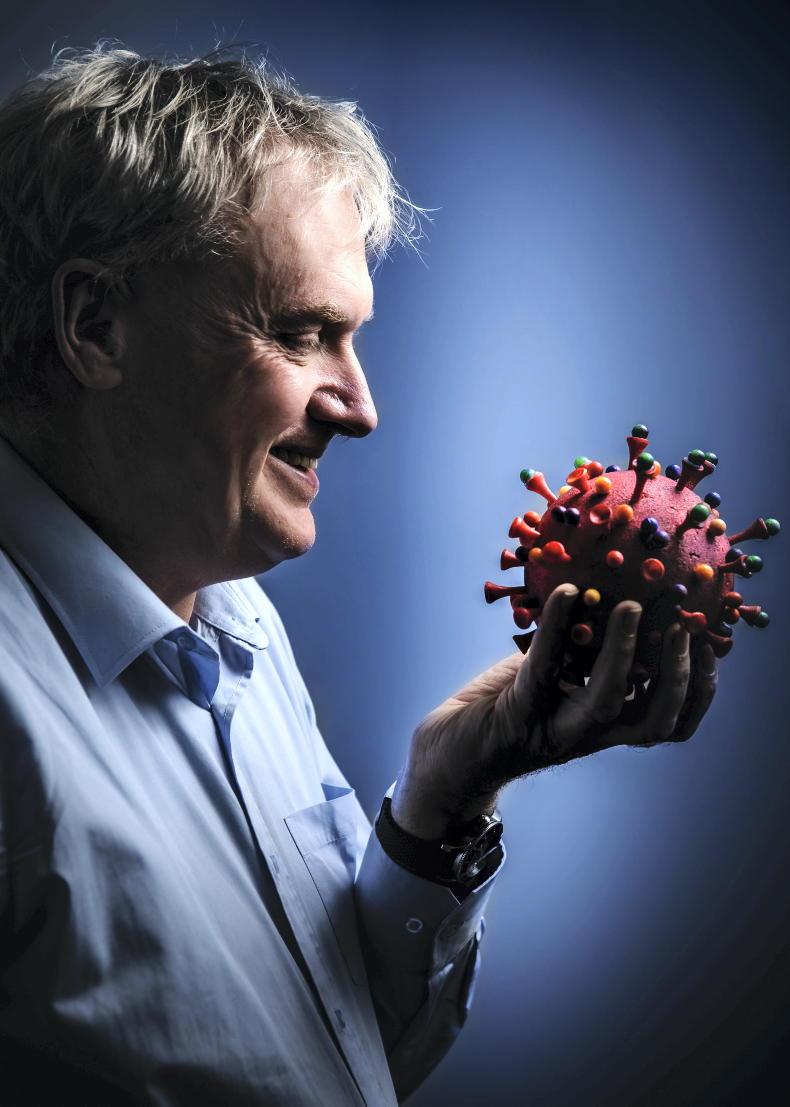

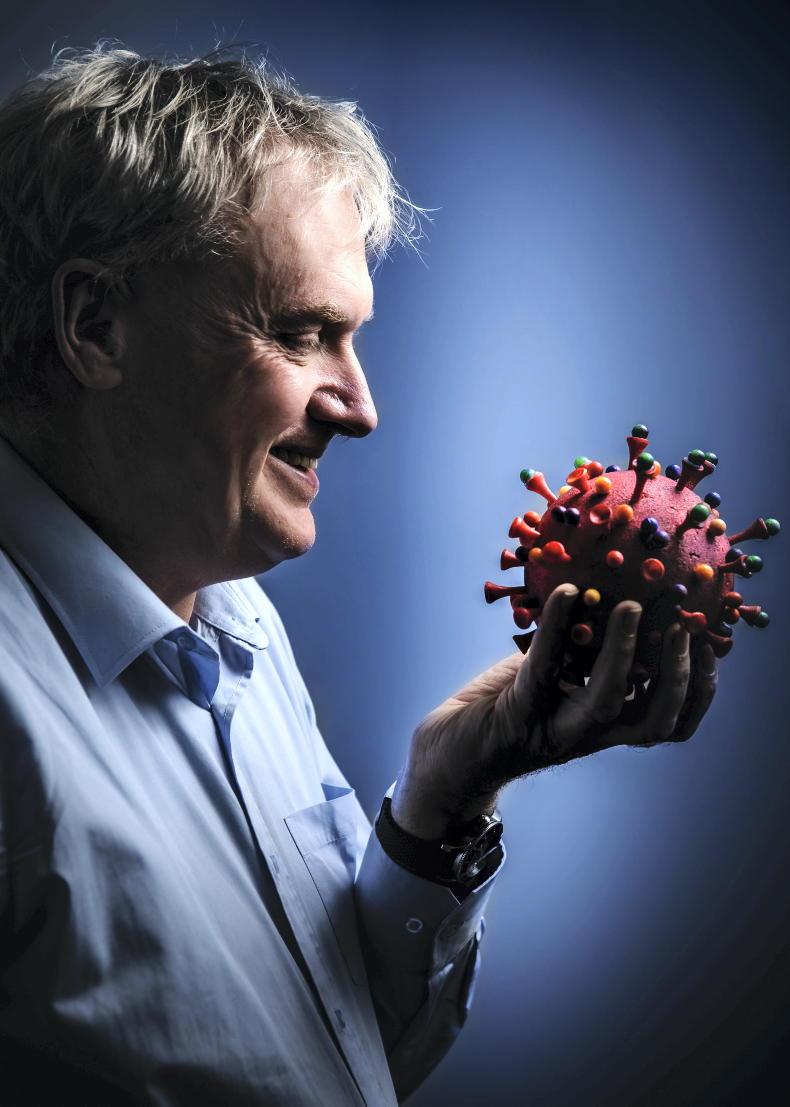

Luke O’Neill is in a band called The Metabollix. \ Philip Doyle

Although we may not be able to ascertain exactly whose idea the smallpox/cowpox vaccination was, Luke says what is certain is that farmers do tend to have good immune systems.

“They’ve even done studies, putting people on a farm for a month, and it will protect them against asthma later in life. Isn’t that incredible? There’s something on farms that protects people against allergy, asthma mainly. They call it the hygiene hypothesis. So a bit of dirt is good for you, basically. It’s probably something in the dung, some bacteria that you’re inhaling.

“What happens there is, if you’re young, especially if you’re a child or a baby actually, if your immune system is exposed to a bit of dirt, it teaches it how to tell friend from foe. If you don’t have that you’re going to be hypersensitive. So being on a farm is good for you basically. Secondly, outdoors is great, fresh air helps us, sunlight, all those things.”

The road to science

Luke grew up in Bray, Co Wicklow, and says he was always curious about the natural world. Hiking in the Wicklow Mountains as a child, he’d wonder how the mountains were formed and then go to library to research it. He was also curious about everyday items, like how was talcum powder created? Talc is a rock ground down, he informs us.

Interestingly though, in school, Luke’s favourite subject was English. Which shouldn’t be too surprising really, considering his latest book, Never Mind the B#ll*cks, Here’s the Science, won the An Post Irish Non-Fiction Book of the Year in 2020. It was a very influential teacher in fifth year that drew him towards science.

“Science then began to dominate for me. It was this biology teacher when I was in fifth year. His name was Fran Mooney. He was the coolest guy. He was 26 at the time. I think we were his first class. His hair was to his shoulders. He’d torn jeans,” Luke recalls.

“This is a bit controversial, but I went to a Catholic school, Pres Bray, and every class was started with a prayer. He said, ‘We’re not doing that. This is a science class’. We were all like, ‘Good on you Fran’.

“You need mentors and you need people to inspire you, especially when you’re a teenager, I think it’s extremely important. The great line is: it can be the singer not the song. In other words, if you’ve the right singer, the song sounds great. That’s what teaching is in essence. That’s when it began for me.”

Luke initially considered studying medicine, but in the end veered towards science. He did his undergrad in Trinity, his PhD in the Royal College of Surgeons in London and went to Cambridge for his postdoctoral research.

Up until his first scientific discovery during his PhD, Luke was actually a little uncertain of his chosen path in science. But the discovery changed things, knowing these discoveries could make new medicines to help people gave him a real sense of purpose.

The ultimate dream is that you’re going to benefit humanity in the broadest sense

“For me, I needed something more than just the joy of discovery and that’s trying to make a new medicine, trying to make a treatment for a disease, that became the next big thing for me. My research was always like that from then on.

“The ultimate dream is that you’re going to benefit humanity in the broadest sense. If your discoveries can make a difference it’s even more important. In essence that was the final piece of the puzzle for me; I’m going to stick at it, I’m going to keep going.”

Knowing he wanted to marry lecturing and research, Luke then applied for a job in Trinity, which he got. However, it wasn’t his only offer and some thought he was making the wrong decision.

“My boss in Cambridge said, ‘You’re a bloody idiot taking that job. That’s a backwater’, because Ireland wasn’t famous for research in those days. Trinity was okay, but it wasn’t world class. He said, ‘You should be going to be America. You should be playing for Man United’. Whatever the equivalent was.”

Picking up on the soccer analogy, we inquire what team Trinity would have been at the time?

“Shamrock Rovers,” Luke quips with a smile.

“I came back here and that almost gave me extra motivation, ‘I’ll show you’. He said to me, ‘Luke, if it doesn’t work out you can come back to me anyway’. So it gave me a sort of safety net. But I came back and I began building my lab. Ireland began to change then, there was more investment in research.”

Music matters

While Luke pursued science fervently as a career, music has always been his hobby and he lights up completely when he speaks about it. It’s not unusual for scientists to be musicians, he says. At the closing dinner of conferences, he and some follow scientists would always go up on stage to perform.

In 2017 he organised an immunology congress in the RDS, attended by over 1,000 people. For this he put together a band of scientists and doctors to entertain the masses. They called themselves The Metabollix.

Luke takes a picture of the band at the conference off a shelf and begins to list out the members. “He’s got a PhD in chemistry. She’s got a PhD in immunology. Colm, he’s the chief neonatologist in Holles Street. Drummer, Brian, he’s a neurologist in Beaumont.” The list goes on.

The mission of The Metabollix is quite simple, it’s to make people happy

After this maiden voyage, the band were asked to play Body & Soul Festival. They were also flown to Boston and Australia to play at conferences. “They got two for the price of one with me, because I gave a talk as well,” Luke chuckles.

Pre-pandemic, The MetaBollix also played a monthly gig in a pub called The Dalkey Duck. “The mission of The Metabollix is quite simple, it’s to make people happy,” Luke says. “My dream was, it would be a miserable Friday night, the people are there, they’ve had a hard week at work, they’re pissed off at their boss and we lift them out of it by playing The Rolling Stones and The Beatles.”

Their last gig was actually March 2020, a children’s cancer charity fundraiser in Tanzania. However, things didn’t quite go to plan. Four days before travelling to Tanzania, the band played a fundraising gig for the charity in The Dalkey Duck. They then flew to Tanzania and did the gig. But soon after, Luke found out six people who had been in The Dalkey Duck that night had tested positive for coronavirus.

“I immediately booked flights for us all to leave Tanzania, because I was worried we were all infected. We didn’t even see Tanzania, because there was a risk of infection. We flew back the next day and we were miserable. Still, it was the safest thing to do, none of us had any symptoms, but I knew this virus could spread with no symptoms at this stage.”

We’ve learned why these things matter. It’s a bit of a truism, but we took things for granted

Luke’s next time on stage was slightly less stressful. It was to an empty Gaiety Theatre with Mundy and Sharon Shannon this New Year’s Eve, which he says was totally surreal. When the pandemic is in the rear-view mirror, all parties here are in agreement that a gig is top of the to-do list.

“We’ve learned why these things matter. It’s a bit of a truism, but we took things for granted. Why is music important to us? We never had to ask that because we just did it and we enjoyed it. But now we know it’s essential for us as a species. We know science is important, don’t we? Because science is the way out of this, but equally the arts are extremely important.”

If Luke had gone on the European tour that time, you know what, he probably would have made it big, knowing him.

Read more

Sound advice from the professor

When Professor Luke O’Neill was working as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, he was playing guitar in a band called The Sleeping Arrangements.

They played a lot of pub gigs and at one stage were offered an elusive tour of Europe.

Despite some of his bandmates really wanting to pursue the opportunity, Luke declined. There was another area of his life going very well and he wanted to focus on that.

“Of course some of the guys, they weren’t impressed, ‘We wanted to go and you said no’. I said no because I had just made a big discovery in the lab.

“I realised if I leave that now, that’s a missed opportunity. If I said yes, I may never have come back,” Luke muses with a laugh.

Now a world-renowned professor of biochemistry and immunology at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), music’s loss was certainly science’s gain. Luke’s not out of the gigging scene completely though, but more on that later.

As well as researching medicines to treat COVID-19 with his team, throughout the pandemic Luke has been to the forefront of communicating scientific messages to the public in the media.

Luke O'Neill is an immunologist at Trinity College Dublin. \ Philip Doyle

His ability to make science accessible to the masses has seen his popularity sore in the current climate.

However, it’s important to note this is not a new venture for Luke. Distilling science to make it understandable has been a long-term mission of his. For him, it’s about getting people to understand the science behind things. If some people are encouraged to pursue science as a career, even better.

We meet Luke at the Trinity Biomedical Sciences Institute for a socially distanced chat. Luke, if you have heard him on TV or radio before, is just as you would expect him to be, extremely positive!

In fact, meeting him, it’s very easy to see why he’s so in demand at the minute. His mood is infectious. The ‘COVID gloom cloud’ disperses when you’re around him. Not in the sense that it’s ignored, but the whole thing feels more manageable. After speaking with him, you feel happy and hopeful, rejuvenated by his presence.

Luke’s positive outlook, he believes, is both somewhat innate and moulded by his profession.

“I think it’s partly my disposition, we’re all a bit different, aren’t we? But also to be a scientist, you have to be optimistic. The reason is: your experiments are usually failing, because your idea is wrong, you can’t prove it or the machine breaks down. You get back up on the horse again,” he explains.

“The most successful scientists have the capacity to bounce back from stuff not working out. If science was easy, we would have discovered a cure for cancer, remember. It’s very difficult, so you have to have that sense of hope, that if I have a new idea or I change my idea – it’s trial and error –I’ll go again. I suspect that’s where the optimism comes from.

“With this one (COVID-19), I knew from the very start science would beat it. I could say that because I know all the scientists, I know all the companies, I know they’re working very hard. The brightest and best people in the world are trying to get a vaccine treatment and I knew they’d win.”

Even though we may still be in the thick of the pandemic at present, Luke says there’s absolutely reason to be hopeful. Vaccines are coming fast, alongside very positive signs from countries like Israel, who are far more advanced in their vaccine rollout. All of the vaccines, including AstraZeneca, will prevent you getting sick and ending up in hospital.

Farm boosts immunity

On the subject of vaccines, Luke has a tit-bit of information for Irish Country Living readers specifically. The first vaccine was invented by a farmer, well sort of!

It was a well-known folktale during the smallpox outbreak that milk maids were often immune to the disease, this turned out to be due to their exposure to cowpox. The first successful vaccine trial is attributed to Edward Jenner, a medical doctor. But a farmer that lived close to him, Benjamin Jesty, claimed he was the first to discover injecting someone with cowpox could prevent smallpox.

Edward Jenner received widespread recognition; money from the UK government, Napoleon commended him and the empress of Russia sent him a diamond. Benjamin Jesty contacted the houses of parliament saying he wanted recognition. He was given a special gift of a gold lancet.

Luke O’Neill is in a band called The Metabollix. \ Philip Doyle

Although we may not be able to ascertain exactly whose idea the smallpox/cowpox vaccination was, Luke says what is certain is that farmers do tend to have good immune systems.

“They’ve even done studies, putting people on a farm for a month, and it will protect them against asthma later in life. Isn’t that incredible? There’s something on farms that protects people against allergy, asthma mainly. They call it the hygiene hypothesis. So a bit of dirt is good for you, basically. It’s probably something in the dung, some bacteria that you’re inhaling.

“What happens there is, if you’re young, especially if you’re a child or a baby actually, if your immune system is exposed to a bit of dirt, it teaches it how to tell friend from foe. If you don’t have that you’re going to be hypersensitive. So being on a farm is good for you basically. Secondly, outdoors is great, fresh air helps us, sunlight, all those things.”

The road to science

Luke grew up in Bray, Co Wicklow, and says he was always curious about the natural world. Hiking in the Wicklow Mountains as a child, he’d wonder how the mountains were formed and then go to library to research it. He was also curious about everyday items, like how was talcum powder created? Talc is a rock ground down, he informs us.

Interestingly though, in school, Luke’s favourite subject was English. Which shouldn’t be too surprising really, considering his latest book, Never Mind the B#ll*cks, Here’s the Science, won the An Post Irish Non-Fiction Book of the Year in 2020. It was a very influential teacher in fifth year that drew him towards science.

“Science then began to dominate for me. It was this biology teacher when I was in fifth year. His name was Fran Mooney. He was the coolest guy. He was 26 at the time. I think we were his first class. His hair was to his shoulders. He’d torn jeans,” Luke recalls.

“This is a bit controversial, but I went to a Catholic school, Pres Bray, and every class was started with a prayer. He said, ‘We’re not doing that. This is a science class’. We were all like, ‘Good on you Fran’.

“You need mentors and you need people to inspire you, especially when you’re a teenager, I think it’s extremely important. The great line is: it can be the singer not the song. In other words, if you’ve the right singer, the song sounds great. That’s what teaching is in essence. That’s when it began for me.”

Luke initially considered studying medicine, but in the end veered towards science. He did his undergrad in Trinity, his PhD in the Royal College of Surgeons in London and went to Cambridge for his postdoctoral research.

Up until his first scientific discovery during his PhD, Luke was actually a little uncertain of his chosen path in science. But the discovery changed things, knowing these discoveries could make new medicines to help people gave him a real sense of purpose.

The ultimate dream is that you’re going to benefit humanity in the broadest sense

“For me, I needed something more than just the joy of discovery and that’s trying to make a new medicine, trying to make a treatment for a disease, that became the next big thing for me. My research was always like that from then on.

“The ultimate dream is that you’re going to benefit humanity in the broadest sense. If your discoveries can make a difference it’s even more important. In essence that was the final piece of the puzzle for me; I’m going to stick at it, I’m going to keep going.”

Knowing he wanted to marry lecturing and research, Luke then applied for a job in Trinity, which he got. However, it wasn’t his only offer and some thought he was making the wrong decision.

“My boss in Cambridge said, ‘You’re a bloody idiot taking that job. That’s a backwater’, because Ireland wasn’t famous for research in those days. Trinity was okay, but it wasn’t world class. He said, ‘You should be going to be America. You should be playing for Man United’. Whatever the equivalent was.”

Picking up on the soccer analogy, we inquire what team Trinity would have been at the time?

“Shamrock Rovers,” Luke quips with a smile.

“I came back here and that almost gave me extra motivation, ‘I’ll show you’. He said to me, ‘Luke, if it doesn’t work out you can come back to me anyway’. So it gave me a sort of safety net. But I came back and I began building my lab. Ireland began to change then, there was more investment in research.”

Music matters

While Luke pursued science fervently as a career, music has always been his hobby and he lights up completely when he speaks about it. It’s not unusual for scientists to be musicians, he says. At the closing dinner of conferences, he and some follow scientists would always go up on stage to perform.

In 2017 he organised an immunology congress in the RDS, attended by over 1,000 people. For this he put together a band of scientists and doctors to entertain the masses. They called themselves The Metabollix.

Luke takes a picture of the band at the conference off a shelf and begins to list out the members. “He’s got a PhD in chemistry. She’s got a PhD in immunology. Colm, he’s the chief neonatologist in Holles Street. Drummer, Brian, he’s a neurologist in Beaumont.” The list goes on.

The mission of The Metabollix is quite simple, it’s to make people happy

After this maiden voyage, the band were asked to play Body & Soul Festival. They were also flown to Boston and Australia to play at conferences. “They got two for the price of one with me, because I gave a talk as well,” Luke chuckles.

Pre-pandemic, The MetaBollix also played a monthly gig in a pub called The Dalkey Duck. “The mission of The Metabollix is quite simple, it’s to make people happy,” Luke says. “My dream was, it would be a miserable Friday night, the people are there, they’ve had a hard week at work, they’re pissed off at their boss and we lift them out of it by playing The Rolling Stones and The Beatles.”

Their last gig was actually March 2020, a children’s cancer charity fundraiser in Tanzania. However, things didn’t quite go to plan. Four days before travelling to Tanzania, the band played a fundraising gig for the charity in The Dalkey Duck. They then flew to Tanzania and did the gig. But soon after, Luke found out six people who had been in The Dalkey Duck that night had tested positive for coronavirus.

“I immediately booked flights for us all to leave Tanzania, because I was worried we were all infected. We didn’t even see Tanzania, because there was a risk of infection. We flew back the next day and we were miserable. Still, it was the safest thing to do, none of us had any symptoms, but I knew this virus could spread with no symptoms at this stage.”

We’ve learned why these things matter. It’s a bit of a truism, but we took things for granted

Luke’s next time on stage was slightly less stressful. It was to an empty Gaiety Theatre with Mundy and Sharon Shannon this New Year’s Eve, which he says was totally surreal. When the pandemic is in the rear-view mirror, all parties here are in agreement that a gig is top of the to-do list.

“We’ve learned why these things matter. It’s a bit of a truism, but we took things for granted. Why is music important to us? We never had to ask that because we just did it and we enjoyed it. But now we know it’s essential for us as a species. We know science is important, don’t we? Because science is the way out of this, but equally the arts are extremely important.”

If Luke had gone on the European tour that time, you know what, he probably would have made it big, knowing him.

Read more

Sound advice from the professor

SHARING OPTIONS