The principles of ventilation are simple. In an enclosed space, airborne substances accumulate – they cannot get out.

Facilitating an airflow through this enclosed space will act to displace these substances, replacing them with fresh air.

Many pneumonia-causing viruses and bacteria are airborne.

Ensuring that airflow through a cattle shed is sufficient will help to move these substances and other waste gases away from the animals and reduce the burden on them. Unfortunately, lots of Irish cattle sheds were not designed with this in mind.

The stack effect

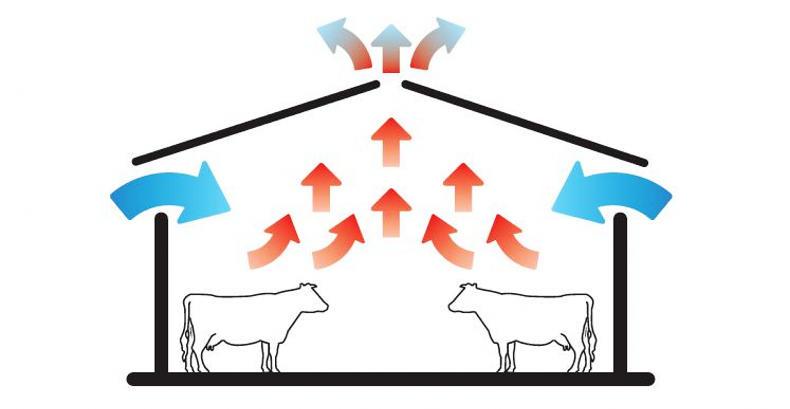

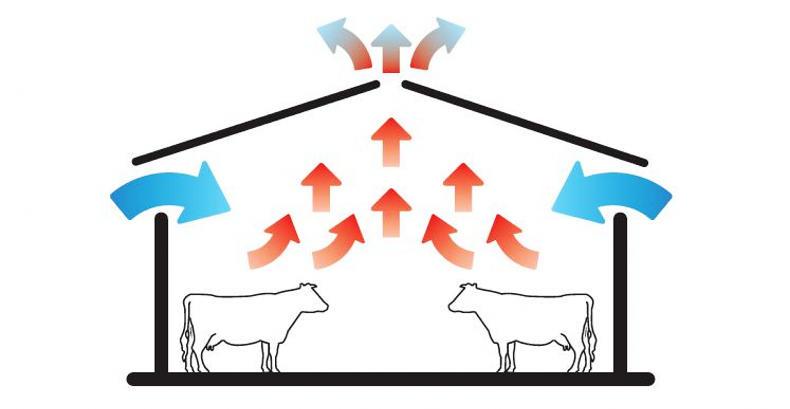

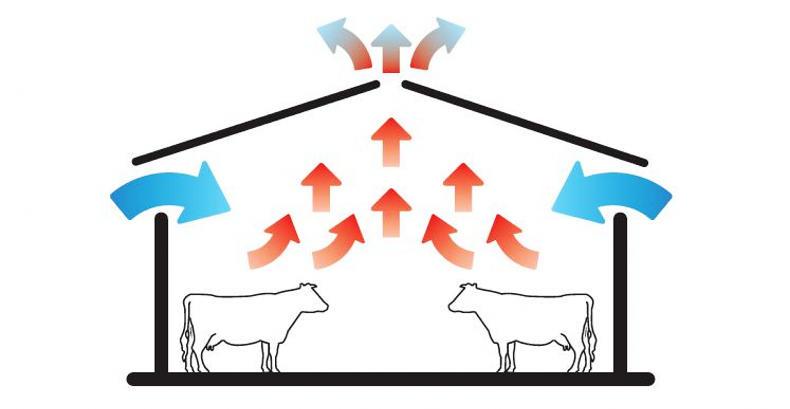

The fact that animals produce heat works to our advantage when trying to properly ventilate sheds. Heat rises and so the heat that our cattle produce in the shed pushes air upwards, towards the roof. This is where our air outlet comes into play – air should have a route to escape from the shed (outlet) at its highest point.

Where the outlet in a shed is insufficient to allow enough air out, stale air – often concentrated with waste gases and airborne bacteria and viruses – accumulates. In this situation, our animals are actively burdened with disease-causing agents and a stressor such as weaning, fighting or a temperature change can weaken their immune systems and let these agents in.

Humans are very sensitive to moving air and animals are no different

In addition, airborne gases produced in animal excretions, as well as moisture, can themselves act as stress-inducers – they should be eliminated too. Think of the ammonia smell that greets you in certain sheds.

As this air leaves the shed, new air is naturally sucked in behind it to fill the void.

This fresh air enters the shed via inlets in the side of the building, ideally just above animal level. The stack effect is illustrated in Figure 1.

The weather can be harnessed to help ventilate sheds, as well as the stack effect. By creating large outlets in the sides of buildings – opposite to the prevailing wind – we encourage air to flow through the upper airspace of the building also, enhancing the stack effect.

In Ireland, wind ventilation is often the most common driver of air movement in livestock sheds.

Draughts

While airflow in a cattle shed is generally a good thing, it should be minimised at animal level.

Can you feel that draught? How many times have you, or has someone in your company, asked that question?

Humans are very sensitive to moving air and animals are no different.

Even air moving at a speed of 0.5m per second will result in young calves burning more energy to warm themselves, leaving less energy available in their systems for performance and, crucially, their immune systems. Draughts can be just as bad as, if not worse than, poor air movement and stuffy conditions. Hence, there should be minimal airflow at animal level – from 0m to 2m. In draughty houses, calves will be seen to huddle along walls.

Inlet and outlet areas

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine has published a number of criteria regarding ventilation that must be met when erecting buildings.

Outlet ventilation must be provided along the full length of the roof apex; 450mm wide for a house up to 15m wide; 600mm wide for a house up to 24m wide; and 750mm wide for larger houses.

A ridge cap over the outlet is not recommended, but when provided it must stand unobstructed and fully clear of the roof by 275mm, 350mm, or 425mm, respectively, for the three widths of houses noted above.

Angled upstands placed on the roof on both sides of the ridge outlet improve the ventilation and prevent most rain access. They are a strongly recommended alternative to ridge capping.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Where spaced sheeting with a gap of at least 20mm is installed over the entire roof, a central ridge outlet, though recommended, is not mandatory.

According to the Department, inlet ventilation must be provided directly under the eaves for the full length of each side of the house.

An unobstructed depth of 450mm must be provided in houses up to 15m wide; 600mm deep in houses up to 24m wide and 750mm deep for larger houses.

Alternatively, to reduce wind-speed and rain, options such as pre-painted steel sheets with ventilation slots (vented sheeting) over their surface can be used for inlet ventilation.

They must be positioned immediately below eaves for the full length of the house and have a minimum depth of 1.5m.

Cobwebs are a sign of inadequate ventilation in sheds.

Case study - Kieran Noonan, Cork

In 2016, Kieran Noonan’s young calves were hit hard with respiratory problems during their first winter. While he didn’t lose any animals, thrive was severely hit.

His birth to 200-day weight gain was 40% to 50% lower than what an autumn-calver with his type of animal should be aiming for, at 0.57kg/day.

Flaws

The BETTER Farm management team identified flaws in the design of his housing. There wasn’t enough airflow in and out of the building to keep stale air moving and prevent the accumulation of disease-causing agents.

A number of adoptions were made to Kieran’s cattle shed.

This vented sheeting was replaced with wind breaker netting. A 15in inlet gap was left at the top.

While the roof sheets were spaced, a capped opening along the apex of the shed’s roof was installed to create a bigger air outlet.The value of vented side sheets as a means for letting in air is questionable, such that it has now been removed from the TAMS spec list. Kieran replaced these with wind-breaker netting, leaving an inlet gap at the top of the wall. Read more

Fodder shortage: ‘it has been a vicious year ... it’s going to be a famine’

‘We have plenty of grass but it’s so wet we can’t get out to graze it'

The principles of ventilation are simple. In an enclosed space, airborne substances accumulate – they cannot get out.

Facilitating an airflow through this enclosed space will act to displace these substances, replacing them with fresh air.

Many pneumonia-causing viruses and bacteria are airborne.

Ensuring that airflow through a cattle shed is sufficient will help to move these substances and other waste gases away from the animals and reduce the burden on them. Unfortunately, lots of Irish cattle sheds were not designed with this in mind.

The stack effect

The fact that animals produce heat works to our advantage when trying to properly ventilate sheds. Heat rises and so the heat that our cattle produce in the shed pushes air upwards, towards the roof. This is where our air outlet comes into play – air should have a route to escape from the shed (outlet) at its highest point.

Where the outlet in a shed is insufficient to allow enough air out, stale air – often concentrated with waste gases and airborne bacteria and viruses – accumulates. In this situation, our animals are actively burdened with disease-causing agents and a stressor such as weaning, fighting or a temperature change can weaken their immune systems and let these agents in.

Humans are very sensitive to moving air and animals are no different

In addition, airborne gases produced in animal excretions, as well as moisture, can themselves act as stress-inducers – they should be eliminated too. Think of the ammonia smell that greets you in certain sheds.

As this air leaves the shed, new air is naturally sucked in behind it to fill the void.

This fresh air enters the shed via inlets in the side of the building, ideally just above animal level. The stack effect is illustrated in Figure 1.

The weather can be harnessed to help ventilate sheds, as well as the stack effect. By creating large outlets in the sides of buildings – opposite to the prevailing wind – we encourage air to flow through the upper airspace of the building also, enhancing the stack effect.

In Ireland, wind ventilation is often the most common driver of air movement in livestock sheds.

Draughts

While airflow in a cattle shed is generally a good thing, it should be minimised at animal level.

Can you feel that draught? How many times have you, or has someone in your company, asked that question?

Humans are very sensitive to moving air and animals are no different.

Even air moving at a speed of 0.5m per second will result in young calves burning more energy to warm themselves, leaving less energy available in their systems for performance and, crucially, their immune systems. Draughts can be just as bad as, if not worse than, poor air movement and stuffy conditions. Hence, there should be minimal airflow at animal level – from 0m to 2m. In draughty houses, calves will be seen to huddle along walls.

Inlet and outlet areas

The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine has published a number of criteria regarding ventilation that must be met when erecting buildings.

Outlet ventilation must be provided along the full length of the roof apex; 450mm wide for a house up to 15m wide; 600mm wide for a house up to 24m wide; and 750mm wide for larger houses.

A ridge cap over the outlet is not recommended, but when provided it must stand unobstructed and fully clear of the roof by 275mm, 350mm, or 425mm, respectively, for the three widths of houses noted above.

Angled upstands placed on the roof on both sides of the ridge outlet improve the ventilation and prevent most rain access. They are a strongly recommended alternative to ridge capping.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Where spaced sheeting with a gap of at least 20mm is installed over the entire roof, a central ridge outlet, though recommended, is not mandatory.

According to the Department, inlet ventilation must be provided directly under the eaves for the full length of each side of the house.

An unobstructed depth of 450mm must be provided in houses up to 15m wide; 600mm deep in houses up to 24m wide and 750mm deep for larger houses.

Alternatively, to reduce wind-speed and rain, options such as pre-painted steel sheets with ventilation slots (vented sheeting) over their surface can be used for inlet ventilation.

They must be positioned immediately below eaves for the full length of the house and have a minimum depth of 1.5m.

Cobwebs are a sign of inadequate ventilation in sheds.

Case study - Kieran Noonan, Cork

In 2016, Kieran Noonan’s young calves were hit hard with respiratory problems during their first winter. While he didn’t lose any animals, thrive was severely hit.

His birth to 200-day weight gain was 40% to 50% lower than what an autumn-calver with his type of animal should be aiming for, at 0.57kg/day.

Flaws

The BETTER Farm management team identified flaws in the design of his housing. There wasn’t enough airflow in and out of the building to keep stale air moving and prevent the accumulation of disease-causing agents.

A number of adoptions were made to Kieran’s cattle shed.

This vented sheeting was replaced with wind breaker netting. A 15in inlet gap was left at the top.

While the roof sheets were spaced, a capped opening along the apex of the shed’s roof was installed to create a bigger air outlet.The value of vented side sheets as a means for letting in air is questionable, such that it has now been removed from the TAMS spec list. Kieran replaced these with wind-breaker netting, leaving an inlet gap at the top of the wall. Read more

Fodder shortage: ‘it has been a vicious year ... it’s going to be a famine’

‘We have plenty of grass but it’s so wet we can’t get out to graze it'

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

Under such upstands, the roof-sheet cannot extend 50mm on each side to prevent rainwater dripping from the upstand.

SHARING OPTIONS