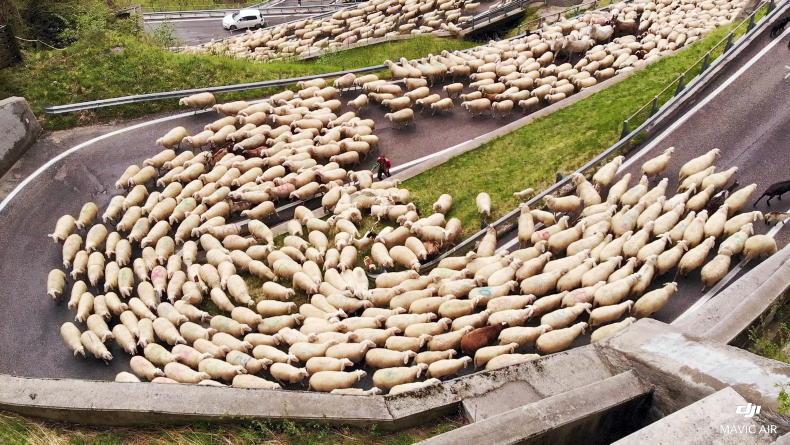

The movement of over 1,500 sheep on a steep road that winds up into the mountains is a glimpse into the annual migration of some of Italy’s flocks.

This video, captured by Alberto Moretti, show the sheer scale of the movement of three combined flocks, and he spoke to one of the shepherds, Renato, about the task.

Born in Bellamonte, Renato lives now in Val di Fiemme in Trentino, which is in northern Italy, in the Dolomite mountains.

Renato is a fourth-generation sheep farmer and his family is known by the nickname the “Diga” family. The word means “dike” and refers to his great grandfather, who moved to the area to build the Forte Buso dam in the 1950s to generate hydroelectric power.

Renato’s flock is known as “gregge del Diga” as a result.

He and his family move, on average, between 1,500 and 1,900 sheep up to the mountain every year, with a peak of 2,200 one year.

The flock of over 1,500 requires three shepherds to move. \ Alberto Moretti

Known as “transhumance”, the practice of moving livestock from one grazing ground to another has a seasonal cycle.

In Renato’s case, the movement of the flock starts in early November, with the sheep gradually moving from Trentino in the highlands to the lowlands, and the back again to the highlands, where the grass is better, as spring ends and summer begins around June.

In all, the journey is eight months long and covers 2,000km a year and an average of 12-15km a day. Each flock of 1,500 to 2,000 sheep requires at least three shepherds.

In all, the journey is eight months long and covers 2,000km a year and an average of 12-15km a day. \ Alberto Moretti

Renato’s sheep are a cross between the Bielllese, described as a prettier and bigger type, and the Bergamasca, a tall sheep. These crossbred sheep are bigger than standard. A yearling can weigh up to 50kg after five months and they are used for meat, mainly destined for the Muslim market. A grown ewe weighs up to 100-110kg.

Goats, donkeys and dogs

But it’s not just sheep in the flock. There are a range of other animals joining them on the journey.

Goats are brought along to act as foster mothers to feed any young lambs whose mothers die. Renato has 10 goats in his flock.

Donkeys and mules are used when cars cannot reach certain points. They are used to carry heavy loads such as salt bags and also to carry injured small animals.

Donkeys are used to carry loads and sometimes sheep in areas where vehicles cannot reach. \ Alberto Moretti

Renato has two types of dogs working with his flock.

Lagorai dogs are used to contain the flock and track for any scattered sheep. They are an ancient Italian dog breed that dates back to the neolithic era. They are a tough, sound and athletic dog known for their docility.

The other dogs are Maremma sheepdogs, guardian dogs that defend the flock against attacks.

“Unfortunately, wolves travel in pack and guard dogs cannot do anything against them. Bears are too strong and again no defence,” Renato told the Irish Farmers Journal.

His flock has been attacked six times in his life by wolves and each time had losses of 40 sheep. The wolves only ate 3-4kg of meat despite the ferocity of the attacks, he said.

Renato and the region’s shepherds have lobbied the EU and local governments to take some action on wolves but, he says: “Public opinion protects wolves and bears and never shepherds and their flocks.”

His flock has been attacked six times in his life by wolves

The shepherds are compensated by the EU for animals lost to attacks, but Renato says that it is still “a great loss, a feeling of dismay torment and impotence”.

The flock has a shepherd with them at all times, although they need less attention when they are in the lowland valley than they do on the mountains.

The sheep have an entourage that includes dogs, donkeys and goats. \ Alberto Moretti

The eight-month journey is tough on animals and some ewes lamb en route, while others die and some may be sold on the way.

As is the case in Ireland, the wool from the sheep has plummeted in value.

“The income of selling wool is nothing because nobody wants wool anymore,” Renato explains. It costs the shepherds to shear the sheep and dispose of the wool.

At 1.5kg of a fleece per ewe, his flock produces 1.8t of wool every year.

Farm income

While there is a support payment for the mountain pasture each farmer grazes, there is no support for the movement of the sheep to and fro.

Unsurprisingly given the level of dedication required, the transhumance tradition has been on the wane, albeit with recent interest from some young people.

“It’s a life of sacrifice. You need to love nature and animals, rural life,” says Renato. “You will be eight months away from family and you must not mind the weather.”

Renato Diga’s flock of over 1,500 sheep moves between the highlands and lowlands in an eight-month seasonal cycle. \ Alberto Moretti

It’s also not a very well paid job.

Renato supplements his income with a part-time job as a truck driver. In summer and when the flock is closer to home, he splits his time between flocks and truck.

Despite the income challenges, he is keen to continue shepherding. He says it’s all about continuing a four-generation tradition, the love for animals and a job that goes back to the previous century.

Tradition under pressure

Like farmers all over the world, tradition can come under pressure.

In recent years, shepherds have been criticised for the effect the movement of several thousand sheep can have en route.

The flock must travel through towns and there has been criticism of them for dirtying the streets.

“When these are regional or provincial routes then it’s more difficult because of traffic jams, dirt on the road, flocks eating not only grass but plants and flowers, also they sometimes damage properties,” Renato explains to Alberto for the Irish Farmers Journal. “So these flocks are not always well accepted in populated cities.”

Thanks to Alberto Moretti for his videography and translation skills.

The movement of over 1,500 sheep on a steep road that winds up into the mountains is a glimpse into the annual migration of some of Italy’s flocks.

This video, captured by Alberto Moretti, show the sheer scale of the movement of three combined flocks, and he spoke to one of the shepherds, Renato, about the task.

Born in Bellamonte, Renato lives now in Val di Fiemme in Trentino, which is in northern Italy, in the Dolomite mountains.

Renato is a fourth-generation sheep farmer and his family is known by the nickname the “Diga” family. The word means “dike” and refers to his great grandfather, who moved to the area to build the Forte Buso dam in the 1950s to generate hydroelectric power.

Renato’s flock is known as “gregge del Diga” as a result.

He and his family move, on average, between 1,500 and 1,900 sheep up to the mountain every year, with a peak of 2,200 one year.

The flock of over 1,500 requires three shepherds to move. \ Alberto Moretti

Known as “transhumance”, the practice of moving livestock from one grazing ground to another has a seasonal cycle.

In Renato’s case, the movement of the flock starts in early November, with the sheep gradually moving from Trentino in the highlands to the lowlands, and the back again to the highlands, where the grass is better, as spring ends and summer begins around June.

In all, the journey is eight months long and covers 2,000km a year and an average of 12-15km a day. Each flock of 1,500 to 2,000 sheep requires at least three shepherds.

In all, the journey is eight months long and covers 2,000km a year and an average of 12-15km a day. \ Alberto Moretti

Renato’s sheep are a cross between the Bielllese, described as a prettier and bigger type, and the Bergamasca, a tall sheep. These crossbred sheep are bigger than standard. A yearling can weigh up to 50kg after five months and they are used for meat, mainly destined for the Muslim market. A grown ewe weighs up to 100-110kg.

Goats, donkeys and dogs

But it’s not just sheep in the flock. There are a range of other animals joining them on the journey.

Goats are brought along to act as foster mothers to feed any young lambs whose mothers die. Renato has 10 goats in his flock.

Donkeys and mules are used when cars cannot reach certain points. They are used to carry heavy loads such as salt bags and also to carry injured small animals.

Donkeys are used to carry loads and sometimes sheep in areas where vehicles cannot reach. \ Alberto Moretti

Renato has two types of dogs working with his flock.

Lagorai dogs are used to contain the flock and track for any scattered sheep. They are an ancient Italian dog breed that dates back to the neolithic era. They are a tough, sound and athletic dog known for their docility.

The other dogs are Maremma sheepdogs, guardian dogs that defend the flock against attacks.

“Unfortunately, wolves travel in pack and guard dogs cannot do anything against them. Bears are too strong and again no defence,” Renato told the Irish Farmers Journal.

His flock has been attacked six times in his life by wolves and each time had losses of 40 sheep. The wolves only ate 3-4kg of meat despite the ferocity of the attacks, he said.

Renato and the region’s shepherds have lobbied the EU and local governments to take some action on wolves but, he says: “Public opinion protects wolves and bears and never shepherds and their flocks.”

His flock has been attacked six times in his life by wolves

The shepherds are compensated by the EU for animals lost to attacks, but Renato says that it is still “a great loss, a feeling of dismay torment and impotence”.

The flock has a shepherd with them at all times, although they need less attention when they are in the lowland valley than they do on the mountains.

The sheep have an entourage that includes dogs, donkeys and goats. \ Alberto Moretti

The eight-month journey is tough on animals and some ewes lamb en route, while others die and some may be sold on the way.

As is the case in Ireland, the wool from the sheep has plummeted in value.

“The income of selling wool is nothing because nobody wants wool anymore,” Renato explains. It costs the shepherds to shear the sheep and dispose of the wool.

At 1.5kg of a fleece per ewe, his flock produces 1.8t of wool every year.

Farm income

While there is a support payment for the mountain pasture each farmer grazes, there is no support for the movement of the sheep to and fro.

Unsurprisingly given the level of dedication required, the transhumance tradition has been on the wane, albeit with recent interest from some young people.

“It’s a life of sacrifice. You need to love nature and animals, rural life,” says Renato. “You will be eight months away from family and you must not mind the weather.”

Renato Diga’s flock of over 1,500 sheep moves between the highlands and lowlands in an eight-month seasonal cycle. \ Alberto Moretti

It’s also not a very well paid job.

Renato supplements his income with a part-time job as a truck driver. In summer and when the flock is closer to home, he splits his time between flocks and truck.

Despite the income challenges, he is keen to continue shepherding. He says it’s all about continuing a four-generation tradition, the love for animals and a job that goes back to the previous century.

Tradition under pressure

Like farmers all over the world, tradition can come under pressure.

In recent years, shepherds have been criticised for the effect the movement of several thousand sheep can have en route.

The flock must travel through towns and there has been criticism of them for dirtying the streets.

“When these are regional or provincial routes then it’s more difficult because of traffic jams, dirt on the road, flocks eating not only grass but plants and flowers, also they sometimes damage properties,” Renato explains to Alberto for the Irish Farmers Journal. “So these flocks are not always well accepted in populated cities.”

Thanks to Alberto Moretti for his videography and translation skills.

SHARING OPTIONS