This year will see the end of the first phase of the Beef Data Genomics Programme (BDGP).

The scheme garnered much criticism throughout its five year run, mainly due to the requirement to breed a certain type of animal, namely one that ranks four or five stars on the replacement index.

While many – myself included – still have reservations, the Department and the ICBF must be commended on the job they have done in making Ireland the leading country in the world with regard to beef genomic evaluations.

This has largely been driven by the overall size of the genomic database following the scheme. Ireland currently has over 2m beef genotypes feeding into genetic evaluations.

To put this in context, the next highest are the American Angus Association, with just over half a million.

This week, the Irish Farmers Journal shares some of our concerns about the scheme with ICBF technical director Andrew Cromie.

Shane Murphy (SM): Is the training population of 100,000 from the Beef Genomic Programme (BGP), still used as the base for the genotype?

Andrew Cromie (AC): No, that was the initial work. The training population gets updated with each evaluation. So now, depending on the trait, you’re looking at 300,000 – 400,000 records in the training population.

Andrew Cromie of the ICBF. \ Dave Ruffles

SM: At what stage is genomic information filtered out by real performance? If I reach 50% will the genomic data be no more use?

AC: No, the genomic data will always be used.

SM: It obviously gets outweighed more as time goes on?

AC: In time. Once you start to get over 70%, then obviously the influence of the genomics and parent average declines, but even for a cow with 70% reliability, 30-50% of that proof is still coming from that parent average and genotype.

With regard a sire, as he goes above that, the bulk is coming from the progeny performance.

SM: The scheme in total cost €300m – has it delivered?

AC: There are different ways you can look at this. Is it positive that we’re actually spending that money on animals, or would we have been better to spend it all on something else?

I think in that context, we have to say it’s hugely positive that we have a scheme that actually links to animals and actions –actions that are going to create real value. So it it’s certainly absolutely delivering as a scheme.

If you then strip it back to the question, has it delivered in the context of the genetic improvement part, for example, the genotyping cost, well I think the only way you can really assess that is by looking at the genetic gain that has been made in terms of productivity and also in terms of sustainability.

Even at this stage, you’re looking at two or three times return on the initial investment.

SM: The indexes were created as a tool, but now that farmers are getting paid to breed by them alone, has it moved away from its original purpose?

AC: Yes, and that’s a fair question. That comes back to if you’re confident that the stars are generally taking the industry in the right direction. I have no doubt that if the 20% and 50% requirements weren’t in there, we would not have got the turnaround in terms of genetic gain that has been achieved.

But equally, I acknowledge that was the part of the scheme that caused most difficulty and continues to cause difficulty.

You know, it frustrates breeders and frustrates farmers, yet when you step back from it, you appreciate that on average, it’s taking us in the right direction.

SM: Is there a lot of good breeding being lost because of the programme, if we take the amount of cows that were genotyped as one star, but could have been four or five star given time?

AC: You have to learn to balance that out by saying that there are a lot of poor breeding cows that the programme identified at an early stage and made sure they didn’t have an impact. And similarly on the sire side.

Again, it comes back to the numbers of animals that moved from that five to one is less than a percent. In a percentage of cases, you will have underestimated the animal’s genetic merit and in another percentage of cases, you’ll have overestimated.

SM: The biggest concern for pedigree farmers is a 40% reliability one-star. The data coming in because she’s having one calf a year is very small. She might get there, but the pedigree breeders are taking a hit on her and the progeny that come out of her for eight or 10 years.

AC: Yeah, and all you can do is try and balance that up against some information from pedigree, some additional information from the training population and genotype.

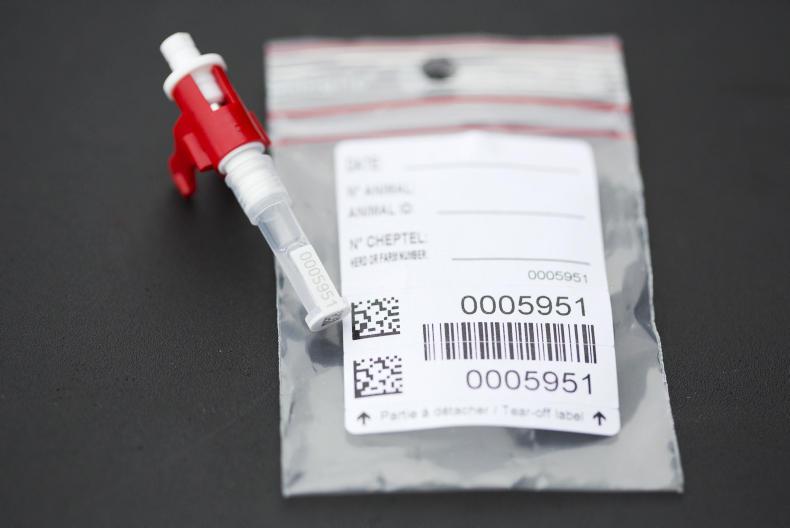

ICBF DNA Sampling kit for for genomics.

What you’ll be saying to pedigree breeders is you really have to look at that as well because there is additional information they don’t know in terms of these maternal traits. Who knows if an animal has easy calving or good fertility by looking at it?

SM: Is 40% reliable enough to base a female breeding programme on?

AC: Well, I think the fact that we’re actually moving the maternal traits in the right direction is just indication that it is. I know it causes angst and problems along the way with individual AI bulls and breeders and cows.

SM: Will the lessons learned from the dairy EBI over the last few weeks be passed on to beef, or is this something that could be an issue in a few years’ time?

AC: Much, much less likely, because the issue that manifested itself in dairy was the rapid high levels of AI and young genomic bulls being used that weren’t in the training population themselves.

If you think about the metrics that we’re talking about, it’s not comparable. We haven’t had the same level of genotyping in the dairy.

SM: Where you don’t have the same level of genotyping in dairy, you do have a lot more accurate data coming in. Are milk data, gestation and calving dates all accurately recorded in beef?

AC: There’s certainly more risks associated with the data on beef for a certain small cohort of animals.

That causes problems in every genetic evaluation in the world, it’s not just an Irish issue, but I certainly don’t believe that there is any more bias in the beef evaluations relative to the dairy.

SM: Comparing dairy and beef, you mention more contemporary groups due to the structure of the national beef herd and an average of 16 cows. Does that have a big effect on evaluations?

AC: In terms of contemporary groups, yes, they’re smaller, but we can do things to make them bigger to combine the data. So, all of what we’re trying to do is just take that management noise out of the evaluation to come back to something that’s more accurate and reflective of the genetic merit.

SM: Is correct parentage the most common use for genotyping pedigree stock?

AC: Yes, yet it’s still a bit frustrating that you have a look at the number of beef bulls out there, and only 72% are actually genotyped. It’s a bit frustrating that it has not become part and parcel of the registration process.

SM: The pedigree breeder is paying €21 to genotype the bull and then come sale time, a new evaluation comes out, the stars drop and they lose money on the sale price. If they don’t genotype, they know they won’t see these big changes around sale time and know what they have to sell.

AC: Now that’s a good argument for why you should do it as a calf!

It could change the pedigree. Is that a good thing or a bad thing for the breeder in that regard? I think it’s a very good thing.

For the second one, they could move for something like calving ease. I would think ultimately that’s a good thing, but short-term, there’s frustration for the breeder.

SM: Talking about calving ease, it’s very good for the commercial man to know this, but the pedigree man is taking the hit and if that happens it’s detrimental to their income for the year.

AC: Yes, that’s the challenge. So again, how do they manage off that? The key is to use a team of bulls, a number of different AI bulls, so all won’t drop. I’m not saying it’s not a challenge. Of course it is.

SM: The key question is, is the pedigree breeder paying for the benefit of the commercial man?

AC: You could flip that around. Is the pedigree breeder gaining for the benefit of the suckler breeder as well? We’re talking a lot about the guys that are losing out.

There are also people that are gaining. If you’re prepared to step back from it and say; ‘This is a new technology, I’m not going to like it all, but there’s new information here which is generally taking us in the right direction as an industry.’

For the fellow who’s using a team of bulls or a mix of AI and stock bull, he’ll see bulls go up and down.

Generally speaking, the bulls that are going up are going to be the ones that will have a happy customer who will come back again.

If the breeder is using genomics to ensure they don’t have pedigree errors, and to identify bulls that should be going to the factory as opposed to being sold, that has to be a

positive, if you talk about it from a genetic gain perspective.

SM: Have you been in talks with the Department about another scheme after BDGP?

AC: There are no discussions, but we’re making progress in these maternal traits and that’s positive – we want to continue that.

We want to continue the focus around carbon and efficiency. Currently, the ones we’re recording under BEEP-S, weaning efficiency type traits and the other ones that kick in as the animal grows, like earlier finishing and all that.

Read more

Genetic gain in fertility without genomics

Letter: the overuse of genomic sires

This year will see the end of the first phase of the Beef Data Genomics Programme (BDGP).

The scheme garnered much criticism throughout its five year run, mainly due to the requirement to breed a certain type of animal, namely one that ranks four or five stars on the replacement index.

While many – myself included – still have reservations, the Department and the ICBF must be commended on the job they have done in making Ireland the leading country in the world with regard to beef genomic evaluations.

This has largely been driven by the overall size of the genomic database following the scheme. Ireland currently has over 2m beef genotypes feeding into genetic evaluations.

To put this in context, the next highest are the American Angus Association, with just over half a million.

This week, the Irish Farmers Journal shares some of our concerns about the scheme with ICBF technical director Andrew Cromie.

Shane Murphy (SM): Is the training population of 100,000 from the Beef Genomic Programme (BGP), still used as the base for the genotype?

Andrew Cromie (AC): No, that was the initial work. The training population gets updated with each evaluation. So now, depending on the trait, you’re looking at 300,000 – 400,000 records in the training population.

Andrew Cromie of the ICBF. \ Dave Ruffles

SM: At what stage is genomic information filtered out by real performance? If I reach 50% will the genomic data be no more use?

AC: No, the genomic data will always be used.

SM: It obviously gets outweighed more as time goes on?

AC: In time. Once you start to get over 70%, then obviously the influence of the genomics and parent average declines, but even for a cow with 70% reliability, 30-50% of that proof is still coming from that parent average and genotype.

With regard a sire, as he goes above that, the bulk is coming from the progeny performance.

SM: The scheme in total cost €300m – has it delivered?

AC: There are different ways you can look at this. Is it positive that we’re actually spending that money on animals, or would we have been better to spend it all on something else?

I think in that context, we have to say it’s hugely positive that we have a scheme that actually links to animals and actions –actions that are going to create real value. So it it’s certainly absolutely delivering as a scheme.

If you then strip it back to the question, has it delivered in the context of the genetic improvement part, for example, the genotyping cost, well I think the only way you can really assess that is by looking at the genetic gain that has been made in terms of productivity and also in terms of sustainability.

Even at this stage, you’re looking at two or three times return on the initial investment.

SM: The indexes were created as a tool, but now that farmers are getting paid to breed by them alone, has it moved away from its original purpose?

AC: Yes, and that’s a fair question. That comes back to if you’re confident that the stars are generally taking the industry in the right direction. I have no doubt that if the 20% and 50% requirements weren’t in there, we would not have got the turnaround in terms of genetic gain that has been achieved.

But equally, I acknowledge that was the part of the scheme that caused most difficulty and continues to cause difficulty.

You know, it frustrates breeders and frustrates farmers, yet when you step back from it, you appreciate that on average, it’s taking us in the right direction.

SM: Is there a lot of good breeding being lost because of the programme, if we take the amount of cows that were genotyped as one star, but could have been four or five star given time?

AC: You have to learn to balance that out by saying that there are a lot of poor breeding cows that the programme identified at an early stage and made sure they didn’t have an impact. And similarly on the sire side.

Again, it comes back to the numbers of animals that moved from that five to one is less than a percent. In a percentage of cases, you will have underestimated the animal’s genetic merit and in another percentage of cases, you’ll have overestimated.

SM: The biggest concern for pedigree farmers is a 40% reliability one-star. The data coming in because she’s having one calf a year is very small. She might get there, but the pedigree breeders are taking a hit on her and the progeny that come out of her for eight or 10 years.

AC: Yeah, and all you can do is try and balance that up against some information from pedigree, some additional information from the training population and genotype.

ICBF DNA Sampling kit for for genomics.

What you’ll be saying to pedigree breeders is you really have to look at that as well because there is additional information they don’t know in terms of these maternal traits. Who knows if an animal has easy calving or good fertility by looking at it?

SM: Is 40% reliable enough to base a female breeding programme on?

AC: Well, I think the fact that we’re actually moving the maternal traits in the right direction is just indication that it is. I know it causes angst and problems along the way with individual AI bulls and breeders and cows.

SM: Will the lessons learned from the dairy EBI over the last few weeks be passed on to beef, or is this something that could be an issue in a few years’ time?

AC: Much, much less likely, because the issue that manifested itself in dairy was the rapid high levels of AI and young genomic bulls being used that weren’t in the training population themselves.

If you think about the metrics that we’re talking about, it’s not comparable. We haven’t had the same level of genotyping in the dairy.

SM: Where you don’t have the same level of genotyping in dairy, you do have a lot more accurate data coming in. Are milk data, gestation and calving dates all accurately recorded in beef?

AC: There’s certainly more risks associated with the data on beef for a certain small cohort of animals.

That causes problems in every genetic evaluation in the world, it’s not just an Irish issue, but I certainly don’t believe that there is any more bias in the beef evaluations relative to the dairy.

SM: Comparing dairy and beef, you mention more contemporary groups due to the structure of the national beef herd and an average of 16 cows. Does that have a big effect on evaluations?

AC: In terms of contemporary groups, yes, they’re smaller, but we can do things to make them bigger to combine the data. So, all of what we’re trying to do is just take that management noise out of the evaluation to come back to something that’s more accurate and reflective of the genetic merit.

SM: Is correct parentage the most common use for genotyping pedigree stock?

AC: Yes, yet it’s still a bit frustrating that you have a look at the number of beef bulls out there, and only 72% are actually genotyped. It’s a bit frustrating that it has not become part and parcel of the registration process.

SM: The pedigree breeder is paying €21 to genotype the bull and then come sale time, a new evaluation comes out, the stars drop and they lose money on the sale price. If they don’t genotype, they know they won’t see these big changes around sale time and know what they have to sell.

AC: Now that’s a good argument for why you should do it as a calf!

It could change the pedigree. Is that a good thing or a bad thing for the breeder in that regard? I think it’s a very good thing.

For the second one, they could move for something like calving ease. I would think ultimately that’s a good thing, but short-term, there’s frustration for the breeder.

SM: Talking about calving ease, it’s very good for the commercial man to know this, but the pedigree man is taking the hit and if that happens it’s detrimental to their income for the year.

AC: Yes, that’s the challenge. So again, how do they manage off that? The key is to use a team of bulls, a number of different AI bulls, so all won’t drop. I’m not saying it’s not a challenge. Of course it is.

SM: The key question is, is the pedigree breeder paying for the benefit of the commercial man?

AC: You could flip that around. Is the pedigree breeder gaining for the benefit of the suckler breeder as well? We’re talking a lot about the guys that are losing out.

There are also people that are gaining. If you’re prepared to step back from it and say; ‘This is a new technology, I’m not going to like it all, but there’s new information here which is generally taking us in the right direction as an industry.’

For the fellow who’s using a team of bulls or a mix of AI and stock bull, he’ll see bulls go up and down.

Generally speaking, the bulls that are going up are going to be the ones that will have a happy customer who will come back again.

If the breeder is using genomics to ensure they don’t have pedigree errors, and to identify bulls that should be going to the factory as opposed to being sold, that has to be a

positive, if you talk about it from a genetic gain perspective.

SM: Have you been in talks with the Department about another scheme after BDGP?

AC: There are no discussions, but we’re making progress in these maternal traits and that’s positive – we want to continue that.

We want to continue the focus around carbon and efficiency. Currently, the ones we’re recording under BEEP-S, weaning efficiency type traits and the other ones that kick in as the animal grows, like earlier finishing and all that.

Read more

Genetic gain in fertility without genomics

Letter: the overuse of genomic sires

SHARING OPTIONS