The risk facing farmers with ash plantations was outlined in a letter to the Irish Farmers Journal two weeks ago – Forestry dream turned into nightmare.

The writer planted 35 acres with ash in 2000, which provided a better financial return “than the 40-odd cattle...on the land up to then”.

However, the plantation has been infected with the fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus that causes ash dieback. As a result, the woodland owner is faced with the following options:

Remove the ash and plant with a replacement species; orRemove the ash and return the land to grazing.If he chooses the first option, he will receive a grant to cover the cost of removal and replanting, but will receive only three annual premium payments as the premium period expires in 2020. Therefore, he faces a 25-year wait before receiving a worthwhile income from his forest.

If he wishes to return the land to grazing he is in contravention of the replanting obligation and has to pay back all grant and premium payments received to date.

Catch-22

He is faced with a classic catch-22 whichever option he takes, resulting in a loss of “around €200,000” he maintained.

The writer wished to remain anonymous, so it is impossible to assess his plantation regards yield, quality and extent of disease. However, from the description, it looks like a well-managed crop.

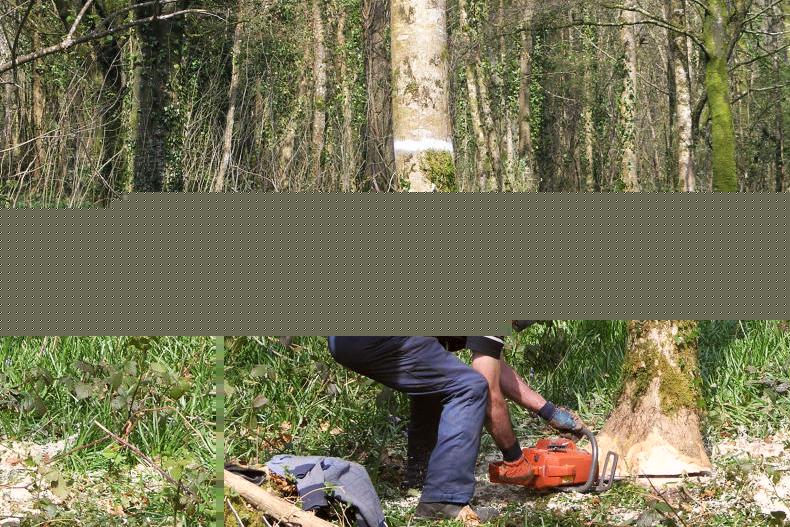

For example, it was thinned three years ago providing a firewood crop, while the cost of harvesting was covered by a Forest Service grant.

Options

Sadly, the letter writer is not the only forest owner faced with this problem, but he may have more options than he realises. For example, if the crop is only partially infected, he can remove the diseased trees over time and thin the remaining crop for firewood and hurley ash.

This option will depend on the speed of the spread of the disease. So far it seems that the spread of ash dieback varies year by year and is not as rapid in mature crops as very young plantations, where the only option is to remove all trees and replant.

If the spread of the disease in mature and semi-mature trees is slow, the advice is to remove only the diseased trees. In addition, woodland owners, along with their forestry advisers and contractors, should thin crops to allow final crop trees to maximise growth for the production of hurley and commercial ash. Partially diseased trees don’t die straight away, so can be salvaged after infection for firewood and even hurleys, so panic felling should be discouraged.

Hurleys

The aim should be to select and retain 400 to 600 ash butts for hurley making. Remember, you only need a straight branch-free stem up to 1.5m to achieve hurley ash quality.

As the original stocking for ash plantations is 3,300 trees per hectare and allowing for two thinnings, there should be between 1,500 and 1,800 stems per hectare standing by year 25 when harvesting hurley ash butts can begin and continue up to year 30 and possibly for a few years more.

Ideally, the crop should be allowed to grow on to at least 60 years to produce timber for furniture and other uses, but this is looking increasingly unlikely as ash dieback takes hold.

Depending on size, age and quality, hurley ash butts can sell for between €40 and €60 each. Allowing for harvesting and administration costs, revenue can average €15,000 to €20,000/ha over a five-year period. This revenue has to cover reforestation costs and a future 25 years without any revenue.

All this presupposes that the woodland can stay alive long enough to produce hurley ash up to at least year 25, with every year after a bonus.

It is vital to retain as many mature and semi-mature ash woodlands in production. This approach will maximise revenue and production, especially for hurley ash, but also allows owners to monitor the spread of the disease and possibly to discover disease-resistant species over time.

The farmer who clearfells the crop before it reaches a top height of 15m can avail of a reconstitution grant to cover the disposal of infected foliage and the cost of replanting.

Owners who wait until the crop exceeds 15m will receive an income from timber, but if the disease wipes out the crop at this stage they forego all reconstitution grant entitlements.

Owners should not be forced to take a gamble on when to fell a crop infected with a disease they did not introduce, nor should they be penalised for planting a native species they were encouraged to establish by the Department.

The Department should provide a reconstitution grant for all ash woodland owners up to at least year 25, which is less than half the rotation. Thereafter, the owner should be entitled to a woodland improvement grant even for woodlands which previously received this grant.

In addition, the planning obligation for reforestation should be removed regardless of the species composition of the replacement crop, providing it has a reasonable biodiversity composition.

Second rotation

options

It is likely at this stage that all ash crops will eventually need replacing. Woodland owners can replant with a suitable conifer or broadleaf alternative. Existing specimen trees that are showing signs of resistance to ash dieback should be retained.

Continuous cover forestry (CCF)

CCF, whereby existing trees are underplanted with suitable species, may be an alternative silvicultural system to clearfelling. It is flexible and can be introduced at any stage and is capable of utilising a wide range of broadleaves and conifers.

Agro-forestry

Agro-forestry is the combined use of agriculture and forestry on the same plot of land. It includes agricultural activities – crops and pasture – and timber production. It only requires a stocking rate of 400 stems/ha (5x5m tree spacing) so the site can be used for sheep grazing from the beginning and cattle as the trees mature. Liam Beechinor’s agro-forest in Co Cork also provides two cuts of silage annually.

Agro-forestry provides sufficient tree cover to qualify as a forest – “tree crown cover of more than 20% of the total area, or the potential to achieve this cover at maturity”. Agro-forestry would require removal of roots of original crop or cutting trees at ground level. In the case of hurley ash, this shouldn’t be a problem, as a section of the root is removed. Plants need to be protected with tree-guards.

The risk facing farmers with ash plantations was outlined in a letter to the Irish Farmers Journal two weeks ago – Forestry dream turned into nightmare.

The writer planted 35 acres with ash in 2000, which provided a better financial return “than the 40-odd cattle...on the land up to then”.

However, the plantation has been infected with the fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus that causes ash dieback. As a result, the woodland owner is faced with the following options:

Remove the ash and plant with a replacement species; orRemove the ash and return the land to grazing.If he chooses the first option, he will receive a grant to cover the cost of removal and replanting, but will receive only three annual premium payments as the premium period expires in 2020. Therefore, he faces a 25-year wait before receiving a worthwhile income from his forest.

If he wishes to return the land to grazing he is in contravention of the replanting obligation and has to pay back all grant and premium payments received to date.

Catch-22

He is faced with a classic catch-22 whichever option he takes, resulting in a loss of “around €200,000” he maintained.

The writer wished to remain anonymous, so it is impossible to assess his plantation regards yield, quality and extent of disease. However, from the description, it looks like a well-managed crop.

For example, it was thinned three years ago providing a firewood crop, while the cost of harvesting was covered by a Forest Service grant.

Options

Sadly, the letter writer is not the only forest owner faced with this problem, but he may have more options than he realises. For example, if the crop is only partially infected, he can remove the diseased trees over time and thin the remaining crop for firewood and hurley ash.

This option will depend on the speed of the spread of the disease. So far it seems that the spread of ash dieback varies year by year and is not as rapid in mature crops as very young plantations, where the only option is to remove all trees and replant.

If the spread of the disease in mature and semi-mature trees is slow, the advice is to remove only the diseased trees. In addition, woodland owners, along with their forestry advisers and contractors, should thin crops to allow final crop trees to maximise growth for the production of hurley and commercial ash. Partially diseased trees don’t die straight away, so can be salvaged after infection for firewood and even hurleys, so panic felling should be discouraged.

Hurleys

The aim should be to select and retain 400 to 600 ash butts for hurley making. Remember, you only need a straight branch-free stem up to 1.5m to achieve hurley ash quality.

As the original stocking for ash plantations is 3,300 trees per hectare and allowing for two thinnings, there should be between 1,500 and 1,800 stems per hectare standing by year 25 when harvesting hurley ash butts can begin and continue up to year 30 and possibly for a few years more.

Ideally, the crop should be allowed to grow on to at least 60 years to produce timber for furniture and other uses, but this is looking increasingly unlikely as ash dieback takes hold.

Depending on size, age and quality, hurley ash butts can sell for between €40 and €60 each. Allowing for harvesting and administration costs, revenue can average €15,000 to €20,000/ha over a five-year period. This revenue has to cover reforestation costs and a future 25 years without any revenue.

All this presupposes that the woodland can stay alive long enough to produce hurley ash up to at least year 25, with every year after a bonus.

It is vital to retain as many mature and semi-mature ash woodlands in production. This approach will maximise revenue and production, especially for hurley ash, but also allows owners to monitor the spread of the disease and possibly to discover disease-resistant species over time.

The farmer who clearfells the crop before it reaches a top height of 15m can avail of a reconstitution grant to cover the disposal of infected foliage and the cost of replanting.

Owners who wait until the crop exceeds 15m will receive an income from timber, but if the disease wipes out the crop at this stage they forego all reconstitution grant entitlements.

Owners should not be forced to take a gamble on when to fell a crop infected with a disease they did not introduce, nor should they be penalised for planting a native species they were encouraged to establish by the Department.

The Department should provide a reconstitution grant for all ash woodland owners up to at least year 25, which is less than half the rotation. Thereafter, the owner should be entitled to a woodland improvement grant even for woodlands which previously received this grant.

In addition, the planning obligation for reforestation should be removed regardless of the species composition of the replacement crop, providing it has a reasonable biodiversity composition.

Second rotation

options

It is likely at this stage that all ash crops will eventually need replacing. Woodland owners can replant with a suitable conifer or broadleaf alternative. Existing specimen trees that are showing signs of resistance to ash dieback should be retained.

Continuous cover forestry (CCF)

CCF, whereby existing trees are underplanted with suitable species, may be an alternative silvicultural system to clearfelling. It is flexible and can be introduced at any stage and is capable of utilising a wide range of broadleaves and conifers.

Agro-forestry

Agro-forestry is the combined use of agriculture and forestry on the same plot of land. It includes agricultural activities – crops and pasture – and timber production. It only requires a stocking rate of 400 stems/ha (5x5m tree spacing) so the site can be used for sheep grazing from the beginning and cattle as the trees mature. Liam Beechinor’s agro-forest in Co Cork also provides two cuts of silage annually.

Agro-forestry provides sufficient tree cover to qualify as a forest – “tree crown cover of more than 20% of the total area, or the potential to achieve this cover at maturity”. Agro-forestry would require removal of roots of original crop or cutting trees at ground level. In the case of hurley ash, this shouldn’t be a problem, as a section of the root is removed. Plants need to be protected with tree-guards.

SHARING OPTIONS