Brothers Michael O’Brien (91) and Fr Rory O’Brien (89) grew up on an Irish farm, where the values of hard work, religious faith and sporting success would allow for an extraordinary reeling in the years.

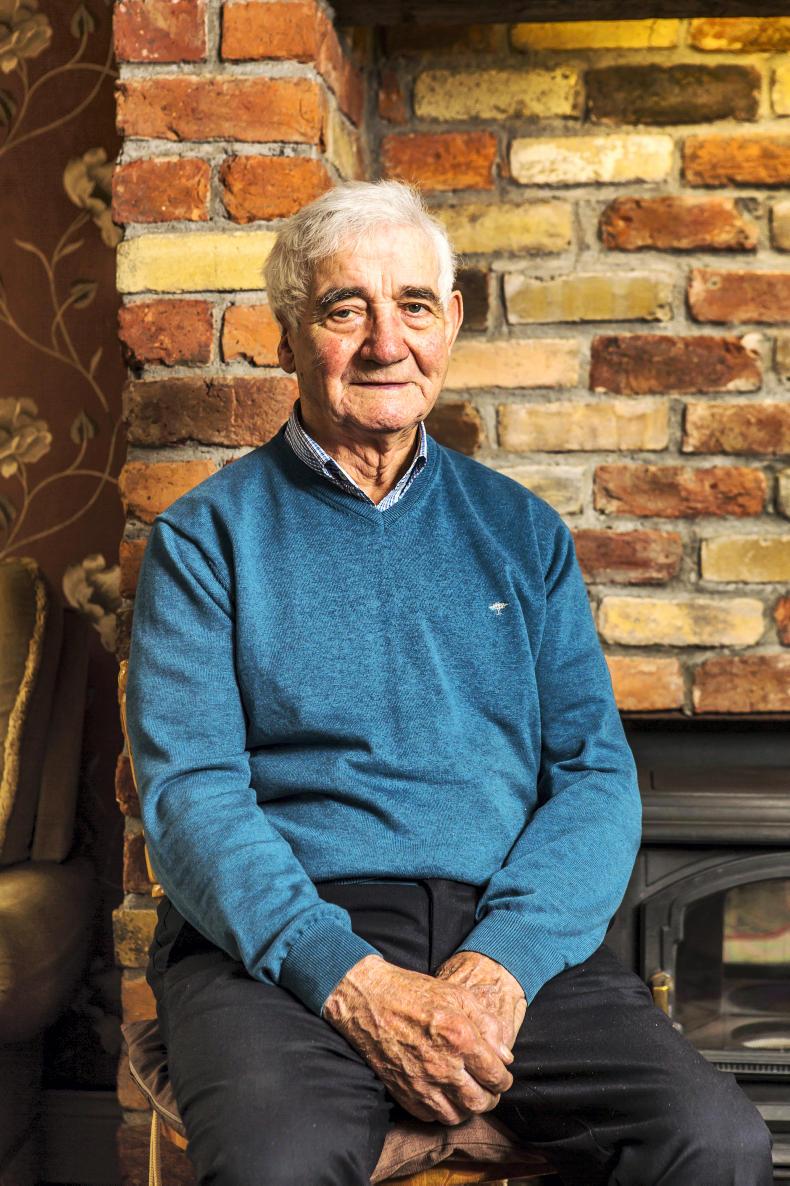

Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

Fr Rory

“The O’Briens farmed from year one, I would say. I think they came here to Ballinamere in about 1860. We had 20 cows, which was a lot at the time. Michael was regarded as a great milker. The rule was ‘fall in as you fall out’. When you milked here, go to the next one, but if there was a kicker, as we called it, you would dilly-dally until the next fella got to her. We always had men working here with us. They got full board: they slept, ate and worked with us. I don’t know how my mother survived it all, with nine of her own children as well. We had a fragmented farm, so she had to get on her bike and deliver out the dinners to the different fields every day.

“It was unusual here because it wasn’t the eldest son who got the farm. Michael got the home farm and Donal, the older brother, went out and did his own thing. He would always say: ‘Michael is the one doing all the work, so leave him in it.’

“In about 1941 a tragedy occurred here. The cows all started having abortions and that really put us on the road. We had to give up dairy completely. At the time they used to say, ‘it’s in the land’. But it was really brucellosis. The change from milking to dry stock and tillage was very hard. It was a great blow to everything here.

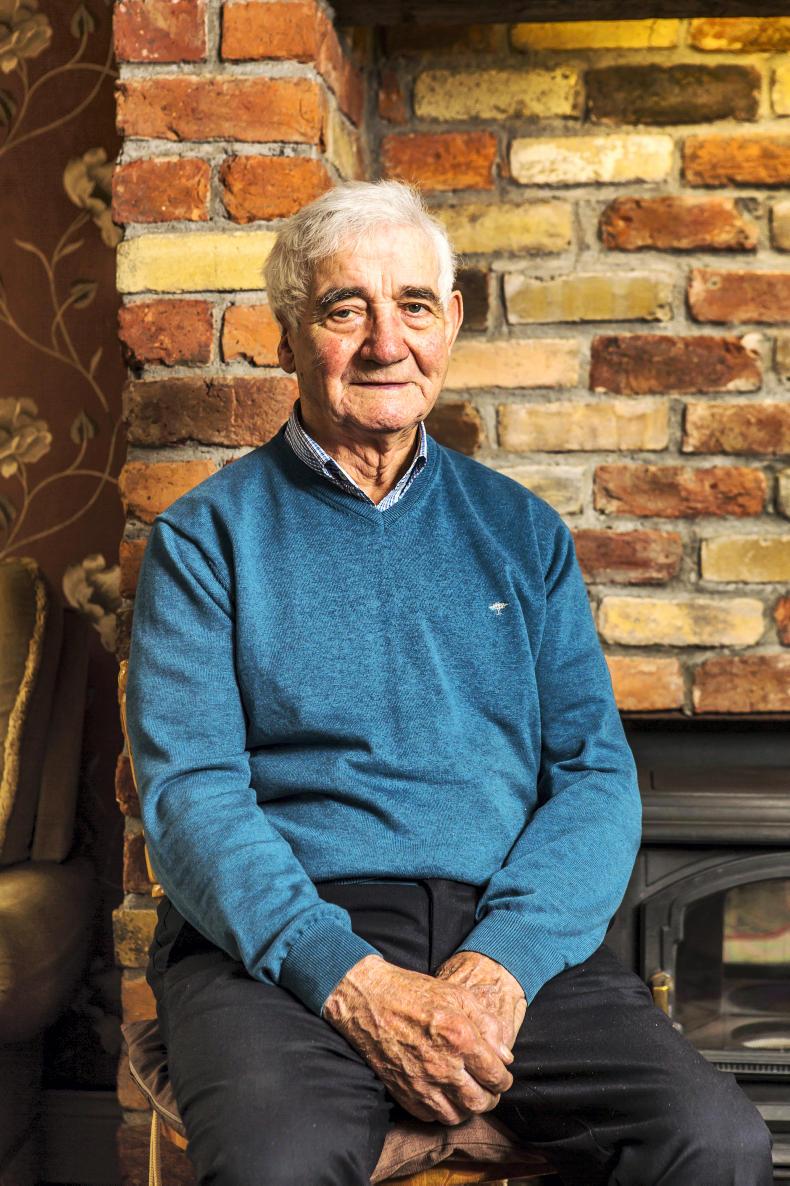

Brothers Michael and Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

“The only outlet we had was hurling. We hurled in the field behind the cow house and togged out on the loft. We chatted all night afterwards. Some people sang, others played cards. The presentation of club medals used to be out on the loft too. When we wanted to raise money we held dances on the loft – completely illegal. We could have had about 200 dancers on the loft, but there was no problem back then with stuff like that. Our sister, Rose, had her wedding reception on the loft and I had my ordination breakfast on it too.

“I was in Kiltegan for seven years’ training for the priesthood. Five of us sailed by boat to Nigeria in September 1955. It took us about three weeks to get there. In the Bay of Biscay we all got sick as the sea was rough. That was my first mission to Africa. I spent 60 years altogether out there. The most significant thing about my stay was the Biafran War in the 1970s. They were tough times for priests in the region, but more for the people of Biafra. We were saving and hiding people from the war. It was a great few years, but you were playing a very dicey game. If you were caught that was it. They became our people and we were fighting for them. Thousands were slaughtered and thousands of bodies were never buried, eventually eaten by dogs and rats. I will never forget the smell. Lots of people ran from their towns once they heard that the army was coming. We were free to go home too, but we stayed to let the war roll over and cost what it may. It was a great decision, because they were our people. We were very lucky that none of our priests from Kiltegan were killed, thank God.”

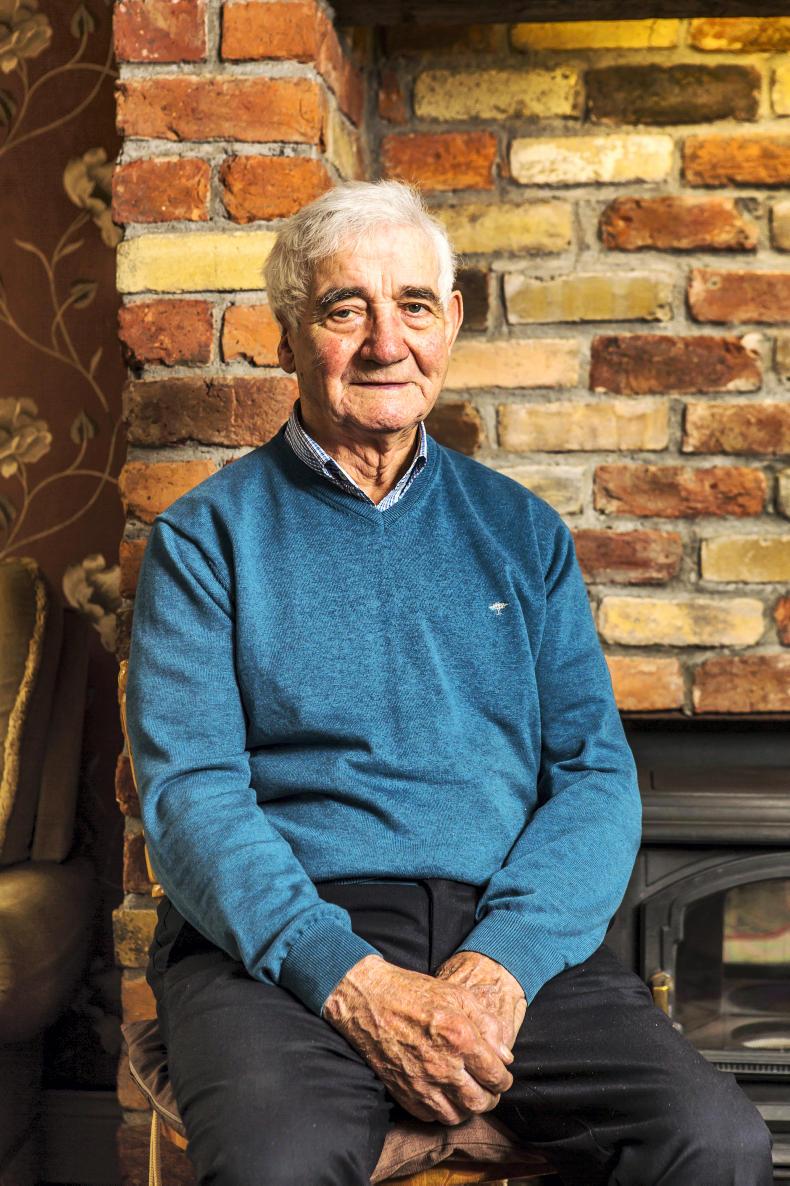

Michael O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

Michael

“We milked and did the milk rounds in Tullamore before we walked to school. I remember one morning going to get the cows before seven o’clock in my bare feet. There was a frosty dew on top of the grass and I’ll never forgot it. We never pasteurised the milk we drank here and it didn’t do us a bit of harm either. I was always very fond of milking. If I got a cow with ‘spins’ (teets) near one another I would milk the four spins at once – two in each hand.

“I went to school at the Christian Brothers and I left as soon as I could, before I was 14. Most people around here left at that age. I used to help my father out on the cart, going in and out of houses in town with milk. We got three half pennies a pint. The cows that time in Offaly were producing about 400 gallons a year.

“I bought my first tractor in 1948, a new Ferguson. A neighbour of ours was killed off it a couple of months after. He was ploughing and we think he fell off the back of it. Back then there would have been no hood on the tractor, or no protection. It was an awful tragedy.

“There were fair days in Tullamore town long ago. It was a tough trade. We would drive our cattle in on a Friday along the road, for six miles and you would spend the day in there. You might sell, but you might have to walk them home again in the evening. The rule was if you sell, buy again that same day to replace them.

Brothers Michael and Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

“There were lads called ‘blockers’ at the fair day. The blocker would know the man who was buying and would step in and offer you a pound less than the original offer. So when the first man came back you would probably sell to him. The bidder would get the animal for cheaper than they should, and the blocker would get a pound or two off his buddy. It was a mean trade.

“In 1966 we [NFA] formed a blockade on the road, as a protest against the Government’s treatment of farmers, with bad prices for livestock, milk and grain. We only allowed the doctor, teacher and priest go by. Some of us were summonsed to £10 or jail. Most of us refused to pay. It was a matter of principle. We were put away in Mountjoy for about 20 days. When we were away the local farmers from around here did all the ploughing for us. There were 14 tractors working in the field. I don’t know if the same would happen nowadays.”

IFJ cover photo 1967.

Brothers Michael O’Brien (91) and Fr Rory O’Brien (89) grew up on an Irish farm, where the values of hard work, religious faith and sporting success would allow for an extraordinary reeling in the years.

Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

Fr Rory

“The O’Briens farmed from year one, I would say. I think they came here to Ballinamere in about 1860. We had 20 cows, which was a lot at the time. Michael was regarded as a great milker. The rule was ‘fall in as you fall out’. When you milked here, go to the next one, but if there was a kicker, as we called it, you would dilly-dally until the next fella got to her. We always had men working here with us. They got full board: they slept, ate and worked with us. I don’t know how my mother survived it all, with nine of her own children as well. We had a fragmented farm, so she had to get on her bike and deliver out the dinners to the different fields every day.

“It was unusual here because it wasn’t the eldest son who got the farm. Michael got the home farm and Donal, the older brother, went out and did his own thing. He would always say: ‘Michael is the one doing all the work, so leave him in it.’

“In about 1941 a tragedy occurred here. The cows all started having abortions and that really put us on the road. We had to give up dairy completely. At the time they used to say, ‘it’s in the land’. But it was really brucellosis. The change from milking to dry stock and tillage was very hard. It was a great blow to everything here.

Brothers Michael and Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

“The only outlet we had was hurling. We hurled in the field behind the cow house and togged out on the loft. We chatted all night afterwards. Some people sang, others played cards. The presentation of club medals used to be out on the loft too. When we wanted to raise money we held dances on the loft – completely illegal. We could have had about 200 dancers on the loft, but there was no problem back then with stuff like that. Our sister, Rose, had her wedding reception on the loft and I had my ordination breakfast on it too.

“I was in Kiltegan for seven years’ training for the priesthood. Five of us sailed by boat to Nigeria in September 1955. It took us about three weeks to get there. In the Bay of Biscay we all got sick as the sea was rough. That was my first mission to Africa. I spent 60 years altogether out there. The most significant thing about my stay was the Biafran War in the 1970s. They were tough times for priests in the region, but more for the people of Biafra. We were saving and hiding people from the war. It was a great few years, but you were playing a very dicey game. If you were caught that was it. They became our people and we were fighting for them. Thousands were slaughtered and thousands of bodies were never buried, eventually eaten by dogs and rats. I will never forget the smell. Lots of people ran from their towns once they heard that the army was coming. We were free to go home too, but we stayed to let the war roll over and cost what it may. It was a great decision, because they were our people. We were very lucky that none of our priests from Kiltegan were killed, thank God.”

Michael O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

Michael

“We milked and did the milk rounds in Tullamore before we walked to school. I remember one morning going to get the cows before seven o’clock in my bare feet. There was a frosty dew on top of the grass and I’ll never forgot it. We never pasteurised the milk we drank here and it didn’t do us a bit of harm either. I was always very fond of milking. If I got a cow with ‘spins’ (teets) near one another I would milk the four spins at once – two in each hand.

“I went to school at the Christian Brothers and I left as soon as I could, before I was 14. Most people around here left at that age. I used to help my father out on the cart, going in and out of houses in town with milk. We got three half pennies a pint. The cows that time in Offaly were producing about 400 gallons a year.

“I bought my first tractor in 1948, a new Ferguson. A neighbour of ours was killed off it a couple of months after. He was ploughing and we think he fell off the back of it. Back then there would have been no hood on the tractor, or no protection. It was an awful tragedy.

“There were fair days in Tullamore town long ago. It was a tough trade. We would drive our cattle in on a Friday along the road, for six miles and you would spend the day in there. You might sell, but you might have to walk them home again in the evening. The rule was if you sell, buy again that same day to replace them.

Brothers Michael and Rory O'Brien. \ Philip Doyle

“There were lads called ‘blockers’ at the fair day. The blocker would know the man who was buying and would step in and offer you a pound less than the original offer. So when the first man came back you would probably sell to him. The bidder would get the animal for cheaper than they should, and the blocker would get a pound or two off his buddy. It was a mean trade.

“In 1966 we [NFA] formed a blockade on the road, as a protest against the Government’s treatment of farmers, with bad prices for livestock, milk and grain. We only allowed the doctor, teacher and priest go by. Some of us were summonsed to £10 or jail. Most of us refused to pay. It was a matter of principle. We were put away in Mountjoy for about 20 days. When we were away the local farmers from around here did all the ploughing for us. There were 14 tractors working in the field. I don’t know if the same would happen nowadays.”

IFJ cover photo 1967.

SHARING OPTIONS