The Department of Agriculture last week released its liver fluke forecast, which pointed to a high risk of liver fluke infestation across the country.

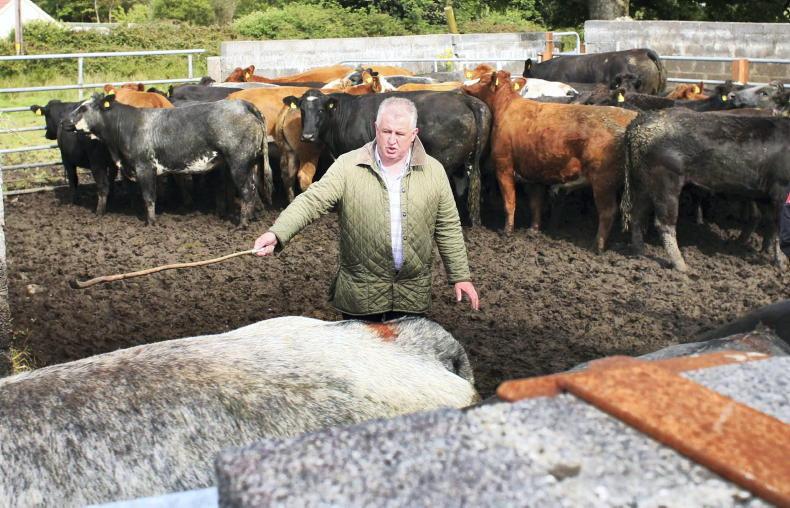

The high-risk status is a view echoed by Roscommon-based veterinary practitioner John Gilmore.

Along with operating a practice and being a director with Farmlab Diagnostics, John also carries out a number of shifts in local processing plants.

He says he has never seen as much liver fluke in cattle and sheep as this back end and, while some infestations are low, there is a presence across a larger spread of animals than normal.

A low infestation, particularly in cattle, can often be masked by animals being in very good condition and consuming a high-quality diet.

It is sometimes the case in these animals that lower performance stemming from health issues is only picked up by regular and accurate performance recording or, in other cases, only once the health of livers have been examined post-slaughter.

However, John fears that given the difficult weather in recent months and knock-on effects on fodder quality and lower body condition in some animals there could be much more problems next spring if these problems are not addressed. This is the case in both cattle and sheep.

We put some reader questions and important treatment questions to John, with a particular focus on sheep-related queries.

Q: What type of liver fluke (acute or chronic) presents the greatest risk at present?

A: The seasonal nature of liver fluke has traditionally presented itself as posing the greatest risk from acute liver fluke in the period August through to October.

This is best characterised by rapid high levels of infestation, which can lead to weakness of the animal, anaemia and sudden death.

We have not seen the same level of mortality in store lambs or ewes that we might have seen a few years ago when similar high levels of rainfall hit and I think this is partly down to farmers being better prepared and moving in quicker to treat animals.

The greatest risk with acute fluke has probably passed and as you progress through November, this transitions to subacute fluke disease being the greatest threat (still some early immature fluke present, but growing numbers of immature and mature fluke).

The risk level is different on every farm and depends on weather and infestation levels on the farm.

We have farms with a known history of liver fluke that have been grazing strategically on drier areas to avoid fluke problems. Some of this has been lambs on drier areas to get around longer withdrawal periods while ewes grazing wetter areas have received treatment.

There is a big variation between farms and this needs to be kept in mind when deciding on the best treatment programme. Losses due to anaemia and sudden death are still possible, but as you get closer to Christmas and the new year, the risk switches to chronic liver fluke, which is traditionally characterised by ill-thrift, oedema or bottle-jaw (fluid accumulating under an animal’s jaw) developing and anaemia.

The rate at which animals can die is generally slower than acute liver fluke, but, as we’ve said already, this may be a year to be extra vigilant, with more pressure potentially on animals.

Q: If chronic liver fluke is the greatest threat, what product should be used?

A: Given there is a large risk from immature and mature fluke, it is important to select a flukicide that treats both of these stages of the life cycle.

Sometimes a mistake is made of trying to find a product that treats all parasites and in doing so some diseases are not adequately covered. It is important to weigh up what the greatest problems are and make sure that treatment is sufficient.

It is also important to alternate between products to reduce the rate of resistance developing.

Some farms have resistance issues with trichlabendazole-based products and if this is the case, it narrows down the range of options available.

There are other good products, with closantel and rafoxanide-based products also commonly used.

Some farmers steer away from Trodax (nitroxynil) as they don’t favour using an injectable product, but it can make up a good part of a robust control plan.

The product is potent, so be careful to follow the guideline amounts based on an animal’s weight.

It is also advised not to administer where there is a known high infestation, as it can bring about a rapid kill which can have other knock-on effects.

Q: How often should I treat animals?

A: Again, this will depend on the farm’s history and risk level. For outwintered flocks in our part of the world, the advice is generally to treat every six to eight weeks.

If you are not using a trichlabendazole-based product, then you will have no other option, as there will be parasites entering the immature stage shortly after treatment.

Flocks that are housed, or will be housed shortly, can take a different approach, depending on the risk level.

Treatment with a product that kills immature and mature liver fluke at or shortly after housing opens up the door to use a product that covers only mature liver fluke at a later stage and gives a better chance to alternate between products.

Q: Is faecal sampling useful in determining the need to treat for liver fluke?

A: I would say that it is a very useful aid if used in the correct manner, but there are some risks if not used correctly.

The first is collecting samples from too small of a sample size. Different animals within a flock or herd can be harbouring different levels of parasites.

I have seen cases where samples have only been taken from one or two animals that have returned a negative result, only for more animals in the group to be suffering a fluke burden.

If you are using faecal samples, you need to collect samples from a good percentage of the group and also monitor performance.

The other concern with basing decisions solely on faecal samples is that animals can have a large fluke burden, but if parasites are present in the early immature or immature form, there will be no eggs being shed in the faeces to identify a problem.

It can take three to four months at the outside from when parasites enter the animal until eggs are being shed, during which time a lot of damage can be caused and performance lost.

I always tell farmers to use all information sources available, with following up the health status of livers from slaughtered animals a really good way to gauge a liver fluke problem.

However, faecal sampling is very useful in determining if a repeat treatment is required for housed animals or determining if the product used has worked.

To get an accurate view on this, a faecal egg count reduction test should be carried out.

However, be careful if going down the route of trying out a product you have doubts with. Consult your vet to ensure a sufficient sample is selected and the remainder of animals are not left exposed to a product not working.

Q: There is a lot of hype about rumen fluke. Eould you recommend treating animals?

A: The incidence of rumen fluke has increased in recent years, but, even more so than liver fluke, there is huge variation between farms.

I have seen farmers take faecal egg samples, where there is a small presence of rumen fluke available, base their treatment decisions solely on rumen fluke and in doing so leaving animals exposed to early immature and immature liver fluke, which is still by far the greater problem. A low positive is not reason enough to treat for rumen fluke.

It is also important to monitor animal performance, with symptoms such as diarrhoea, poor performance and ill-thrift tell-tale clinical signs.

Again, rumen fluke could take a greater toll on animals where it is present and nutrition is limiting.

Q. Is there any other aspects farmers should consider?

A. Along with not selecting the correct product to treat the stage of fluke present, we also see issues at farm level with the weight of sheep being significantly underestimated and poorly calibrated or dosing guns not working delivering a lower than recommended amount. It is important to weigh animals if in doubt and regularly calibrate dosing guns.

SHARING OPTIONS