Speaking to Farmers Journal Scotland, Mark Taylor, research leader in potato group at the James Hutton Institute, explains the challenges in potato breeding and how genetic modification (GM) has a role to play in the laboratory.

“The potato is a particularly hard plant to breed,” believes Mark. “Fraught with difficulties due to the biology of the potato. Most potatoes are tetraploid, which means they have four copies of chromosomes as opposed to two like humans. Therefore potatoes are not self-compatible which means we cannot breed back to parents and get consistent, steady results. In cereals you can do a cross and select the trait you are interested in then go back cross to the original parent to get a new plant with most of the parent’s attributes.”

“This doesn’t happen with potatoes; it’s more like throwing everything up in the air and seeing what happens. It’s more of a numbers game to introduce genetic improvement to potatoes. When you improve one trait you can end up losing another one you wanted. This means it takes 10 years to get a commercially acceptable breed of new potato.”

Potatoes developed in Scotland

The James Hutton Institute’s commercial arm, James Hutton Ltd, carries out conventional commercial breeding on behalf of customers. The have several breeding programmes running concurrently and they produce new varieties fairly frequently. Recent successes include Gemson, a salad variety; Lady Balfour, the number-one organic potato in the UK and Vales’ Sovereign, an early maincrop variety.

“As difficult as potato is, we are successful with it and some other crops are even more complicated like strawberries which are octaploid, so have eight copies of chromosomes,” said Mark.

GM in Scotland

Whilst the Scottish Government has banned commercial trials of GM potatoes in Scotland, there are still quite a lot of GM techniques used in research under carefully contained conditions. It’s a very valuable tool according to Mark. “In the early days of GM crop research (1990s) we did field trials under carefully monitored conditions and with all the appropriate permission from environmental agencies.”

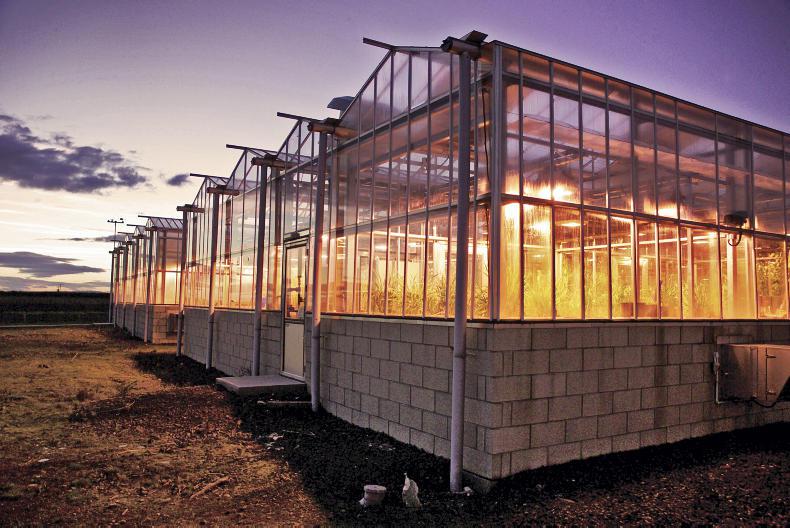

“However, the regulations for getting permission to conduct small-scale research releases in order to field trial GM crops are quite difficult, time consuming and costly, with little support from commercial producers. As an alternative, we use GM plants in contained facilities in a high-containment glass house. Even this work is only carried out once we have conducted a thorough risk assessment and the necessary regulatory permission has been obtained. For example, to make sure there is no escape of pollen from the plants, we remove all the flowers before the pollination stage or we bag the flowers to prevent pollen leaving.”

The Hutton’s facilities have several hundred square metres of plants in a secure facility. This is enough to do work at the experimental level, but is still small scale. Moving potato material to other research facilities (which has been developed through GM) is subject to quite a lot of regulatory control, so it’s not done very widely.

No Frankenstein foods

The types of GM in Scotland are a world away from the Frankenstein foods which hit the headlines.

“All the GM work is focused on looking at the effects of potato genes in potatoes. I don’t know of any examples of people putting genes from other species (eg fish) into potatoes – that is very much a thing of the past.

“Some of the new gene editing techniques do not even introduce any new genes as they can be used to simply turn on or turn off selected genes that impart more useful attributes to the crop,” said Mark.

Using GM in Scotland to develop varieties

GM doesn’t have to be used to engineer new varieties, it is used to understand what different genes do to plants. The plants can then be bred conventionally, with GM used to set the direction and understand desired traits have been gained.

“An alternative approach is to use genetic modification whereby molecular biology methods are used to change the genes or introduce new genes and attributes without breeding,” said Mark.

“What GM enables us to do is to test hypotheses about which genes are important for a particular trait.”

“For example, we have been using GM to look at how we can change one gene important for flesh colour in potatoes.”

The advantage of GM is the ability to link a trait to a specific part of the genome which can then be cross referenced against to see if plants have the trait scientists are after. This helps to speed up the process of looking for new breeds.

“GM allows us to focus in on the one gene which is having this effect. Once we have identified the gene or genes responsible we can then select for them in conventional breeding methods. We are also looking at genes which are resistant to particular diseases. Once found we can track the gene through a breeding programme to ensure plants have the traits we want to see,” said Mark.

GM used with conventional breeding

Knowing what you are looking for means that conventional cross-breeding can be used to get new varieties.

“All of this is being done in a conventional cross-breeding programme but guided by knowing which genes we need to select for. Once we identify the gene we want to track, we make a DNA marker to use in a breeding programme. This means we can look for the gene in naturally occurring bred plants more quickly and efficiently. This is called marker-assisted selection,” said Mark.

To really understand how genes affect an organism scientists have two main options.

“Firstly we can over express a gene to increase its level. Or we can silence the gene or turn it off, using biological compounds that signal to and control a particular gene,” said Mark.

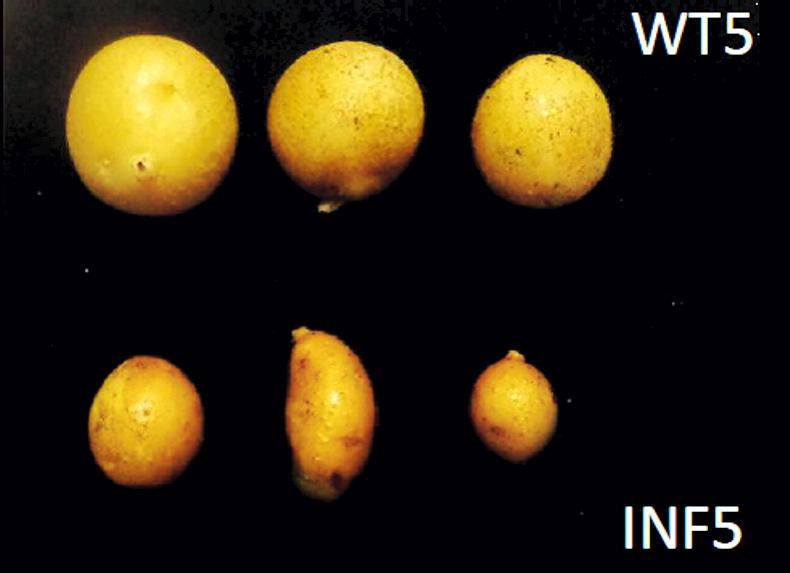

Silenced gene changes potato colour

“One project we are working on shows one particular gene which, if you silence it, you change potato flesh colour making it more yellow-orange,” explained Mark. “We now know the make-up of the genes you want to select if you want a yellow-fleshed potato.”

The yellow-orange pigment is called carotenoid and could have some benefits for eye health. However, Mark believes there needs to be more research to have a certified health claim.

Potato storage solutions

Other projects we have are looking for genes which affect tuber initiation time which is vital for yield. Hutton are also working on genes which affect sprouting in storage.

The UK stores over 1m tonnes of potatoes a year. To maintain quality in storage they are treated with a chemical called CIPC to stop them sprouting. There have been reduced limits to the amount of chemical used, so if the Hutton can develop a potato which you don’t need to put as much CIPC onto, there is a benefit to the industry.

“This is of particular importance to crisp manufacturers because if the quality of potato changes due to sprouting you can’t make decent crisps,” said Mark.

Gene editing a new dawn

Another way of using GM is through gene editing which is a variation on conventional GM where you can very precisely introduce a change to a particular gene. Using specific enzymes and biomolecules as molecular scissors can turn off or introduce a new version of a gene very accurately and precisely.

In fact, some of the gene editing technology does not involve introducing foreign DNA at all. The USDA and EU food standards agency are currently reviewing whether this should even be classed as genetic modification.

“In theory, you can now take a high-performing variety and make a small change to its potato genome and regenerate the plant from a single cell with this modification without any foreign DNA in the plant,” believes Mark.

“We can do this from a single cell from a leaf of a potato plant without losing or changing any of the other useful traits already in the variety.”

Breeding from potatoes with fewer chromosomes

One of these is diploid breeding which is breeding potatoes from varieties which have only two sets of chromosomes compared to the four-copy varieties in most current commercial varieties. Importantly, these diploids tend to be self-compatible and this means scientists can breed back to parents which makes for more stable progress and simply not throwing everything up in the air again when you breed between plants.

Added to this – thanks to the GM work – scientists have more knowledge on the important genes which impact on yield, quality, climate resilience and disease resistance.

“We are working on improving all these traits in a much more rapid timescale,” explained Mark.

“Currently, there are some issues on yield of diploids but potentially it could halve the time taken to get a new variety. Using this approach, you can stack gene improvements together and more methodically.”

Brexit regulation

Mark believes that Brexit will raise a number of regulatory issues. At the moment, GM plant cultivation is covered by EU regulation.Like other environmental legislation it is likely the UK will have similar regulations for GM crops after Brexit. However, it is a devolved matter for the Scottish Government and other devolved administrations and there are already different approaches in the UK.

“Due to the challenges with potato plant breeding we have what is known as a ‘genetic gain problem’ compared to looking at other plants,” said Mark.

“So we are now turning to other technologies to speed up improvements.”

SHARING OPTIONS