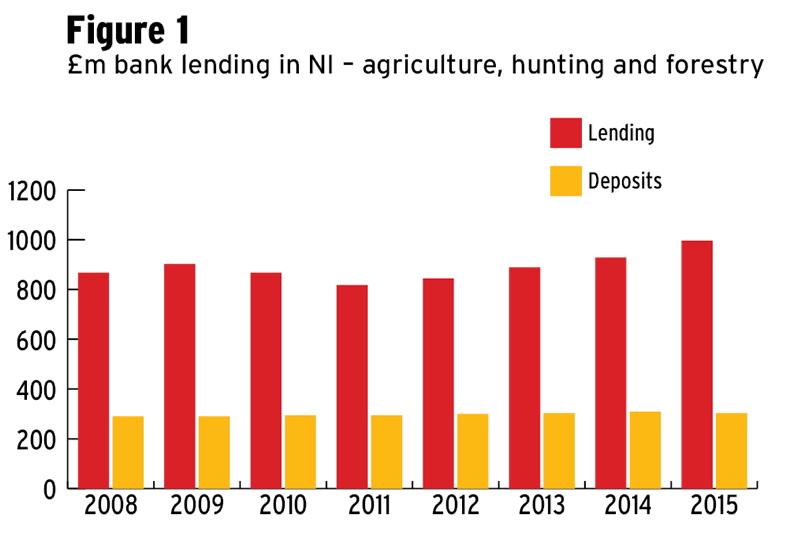

Bank lending to the agricultural sector in NI reached £996m at the end of September 2015. That was up by £67m on the figure one year earlier and continued a trend seen during the previous year (Figure 1).

Lending figures released by the banks since 2013 include the amount loaned by banks based in Britain in addition to the four clearing banks based in NI (Bank of Ireland, Danske, First Trust and Ulster Bank).

Figures prior to 2013 included only the lending by those four and the total in 2009 was around £900m, which suggests that the situation then was probably similar to that in September 2015.

2009 was a particularly bad year for farming income, with the total income from farming (TIFF) estimated to be £197m.

That was far below the income from the Single Farm Payment (SFP) of close to £300m that year. Provisional figures put the estimated TIFF in 2015 down further at £183m and the Basic Farm Payment (plus greening) at £236m. It’s a double whammy as the subsidy payment was hugely reduced due to the exchange rate of the pound against the euro in 2015.

This was one of the stark points made earlier this week in a presentation by Danske Bank’s head of agricultural relations, John Henning, who pointed out that the TIFF in Northern Ireland has been less than the annual Single Farm Payment in four of the past seven years.

Only in 2011, 2013 and 2014 has the local farming sector managed to produce an overall positive margin over and above the subsidy payment.

The bank-lending figures do not include hire purchase and leasing finance made available by other financial institutions, nor do they include merchant credit and other unpaid bills that are believed to be on the increase.

From the bank’s viewpoint, each lending proposition is considered on its own merits. Last year, across all banks, 92% of loan applications were approved. Farmers cannot expect particular sympathy from those at the head of the banks, who are in the business to make profit for their institution.

The often mentioned resilience of farm businesses has been seen in the past and is already in operation in many cases. This includes options from the use of beef bulls in dairy herds to produce calves that bring extra income in the short term to the sale of a building site or sale of a few fields or other assets.

It is noteworthy that bank deposits considered to be from the agri-sector have remained around £300m. They fell by just £6m in 2015. A closer look at the borrowing by individual farm businesses through the DARD Farm Business Survey has indicated that 47% have no borrowings, while 10% have borrowings of more than £100,000. The agri-sector accounts for 33% of loans made by the banks and 23% of the money loaned.

Difficulties

All of the banks admit that they have some dairy farming customers in real difficulty – ranging from mildly serious problems to serious to the danger of business closing down if milk prices don’t improve. The latest indications are that there is little prospect of higher milk prices during much of 2016 and there is every possibility of farm businesses getting much deeper in debt if they are producing milk at a loss.

Henning pointed to the continued rise in milk output and asked where milk supply would have gone if Commissioner Hogan had decided to increase the intervention prices. He argued that the rising volume with current low prices vindicated the Commission stance and said that prices won’t recover until supply comes down closer to demand.

Henning said that restructuring of lending – which could include a period with no repayments or a change in loans to put repayments over a longer period – is a possible short -term solution for some. But he warned that this doesn’t address the core issue if a farm is losing money on every litre and needs to produce a margin over costs. He noted that milk from forage has dropped by 1,700 litres per cow in the past 15 years and said that farmers must concentrate on issues within the farm gate, which they have control over.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: