Sheltering at the side of the Dingle marina from a blustery but bright spring day, Franz Sauerland tells me he lives just 15 minutes away, in Ballyferriter.

Feeling confident (without reason), I attempt to say the place name as Gaeilge. The second the words come out of my mouth, I know they sound wrong.

I ask Franz to pronounce it properly: “Baile an Fheirtéaraigh,” he says and I repeat it back.

Later in the interview I say the name of his former secondary school with more conviction: “Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne. Did I say that one better?”

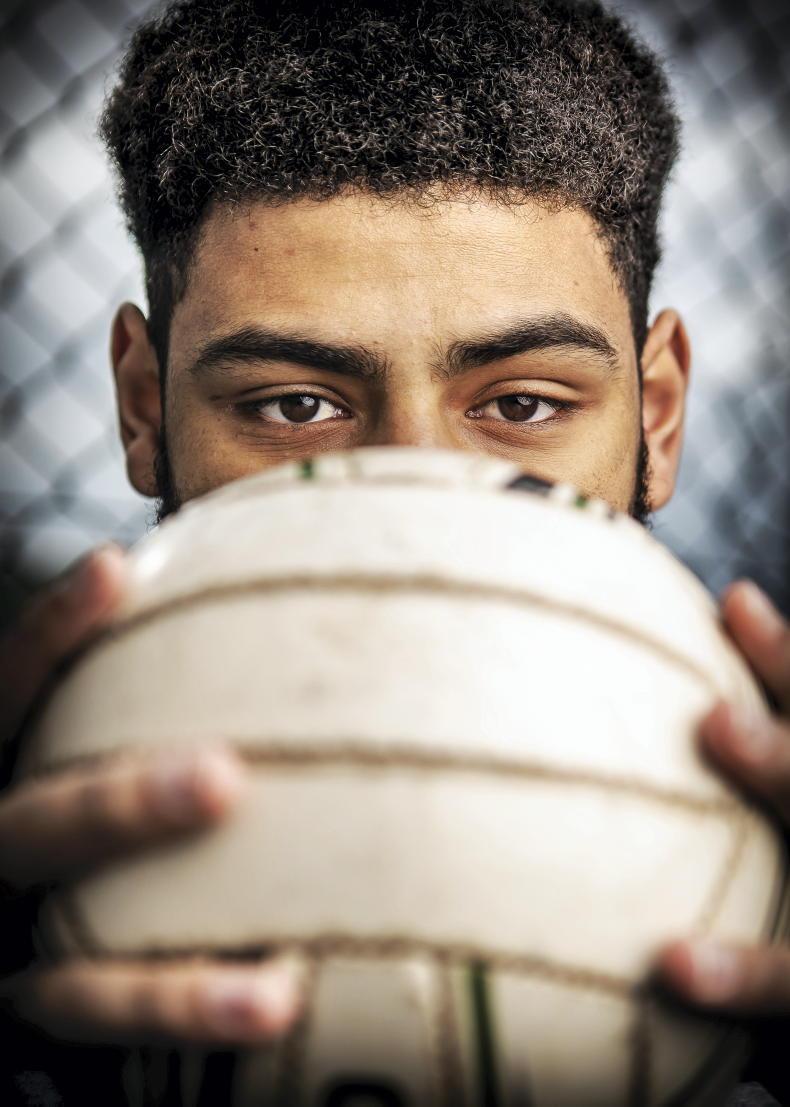

Although he has a true love for GAA, Franz speaks about some racial abuse he has experienced on the pitch. \ Philip Doyle

“You had that one perfect,” Franz says with a kind smile.

When you’re on the “cúpla focal” level and interviewing a Gaeilgeoir, it can sometimes be best to stick to the Béarla, for fear of making a show of yourself. But this was definitely a positive learning experience in the mother tongue.

Franz is a 20-year-old Gaeilgeoir, Gaelic footballer and college student, from, as he said prior to the Irish lesson, Ballyferriter on the Dingle Peninsula. He plays senior club football with An Gaeltacht, as does his older brother, and he’s in the final year of a degree in Irish and Geography in University College Cork (UCC).

Sitting in the town where Franz went to secondary school, the conversation flows through many things. We discuss his love of Gaeilge and football. We also chat about the strong sense of community in and around the Dingle area. Too, we get onto more serious topics; the racism Franz has unfortunately experienced because of the colour of his skin.

Getting to grips with Gaeilge

Franz’s father is German and his mother is Ghanaian, and so, he himself is fluent in three languages; Irish, English and German.

“My father, he was in Germany all his life, but he had business in Ghana and that’s how he met my mother. They came here a year before I was born,” Franz explains.

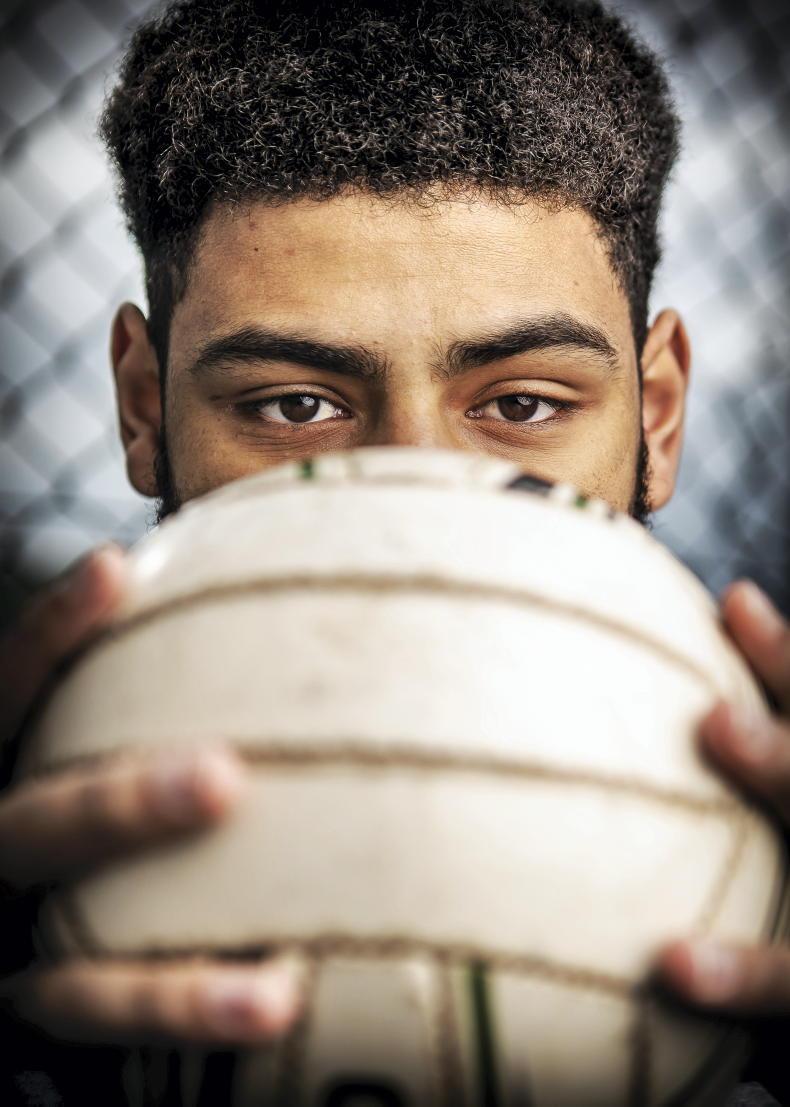

In 2016-2017 Franz was on the Kerry minor team and he also he captained his school’s under-16 and a half team to an All-Ireland. \ Philip Doyle

“I’ve one brother and two younger sisters. The oldest one of the girls is 12, the other one is nine. My brother, he’s two years older than myself. He lived in Ghana for a year. Then they came here and have been here ever since.”

Growing up in the Dingle Gaeltacht, from naíonra (pre-school) through to primary and secondary, education is all as Gaeilge, and so that’s where Franz learned his Irish. Primary school, for Franz, although not a bad experience, was slightly tougher than secondary school.

“I suppose I didn’t know any different, but I always knew I stuck out a bit because of my colour. They made me feel very comfortable though. All the parents now, they’d all be speaking Irish. My mother would be getting texts from the school through Irish. She’d be asking me to translate even though I was only young. I didn’t know everything,” Franz says.

“I found it a bit tougher than secondary school, because I’d made friends by secondary school. Secondary school was a bit different. I’d made a bit of a name for myself through football. Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne, it’s a great school. I’d almost say I miss it. I had a great six years there. I wouldn’t change it for the world, really.”

Racism in football and beyond

At the age of six, Franz started playing football.

“My friends had been playing. They said come along and I asked my mother if I could go. I remember training used to be every Friday at 6pm. I’d always look forward to it every week,” Franz recalls. “I stuck with it, because I’d say I was fairly good at it. I really enjoyed playing, so I just stuck with it and I’m still playing away.”

In 2016-2017 Franz was on the Kerry minor team. In Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne, he captained the under-16 and a half team to an All-Ireland. The following year, sixth year, he was the captain of school’s successful senior team in the Corn Uí Mhuirí. They got to the All-Ireland semi-final that year.

Despite the fond memories Franz has of playing football, and more still to be made, there are also some tough times associated with the sport. Over the years Franz has faced racial abuse while playing. Discussing these incidents, Franz is exceptionally measured, coming across far more mature than his 20 years.

“I wouldn’t say I experienced too much abuse, but it was fairly evident a few times. Even when I was younger, in the younger blitzes, it wouldn’t be coming from the players even, just the parents. I wouldn’t even say it was ignorance. It was more jealousy. I’d be a bit better than their son or something like that.

“They’d be telling me to ‘go play soccer’, that kind of stuff. It might not sound racist, but you can see the way it is [meant]. I know they may not have any cruel intentions, but I’ll never forget it like. That would force some people to give up the sport almost, because they’d be listening to the older people and think, he knows better than I do.”

There was one other incident where a player racially abused Franz. It was at an under 16 club match. Franz wasn’t playing due to injury, but ran onto the pitch to give a teammate water. This particular player, Franz recalls, was quite angry throughout the game.

“He was giving people abuse the whole game, hitting people and all that. He told me to ‘go back to my cotton fields’. That was really the main one I will never forget, that day. I remember just being depressed going home.

“One of the umpires, he was on their team actually, but he was injured as well. He messaged me that night on Facebook – he somehow knew who I was – saying he heard what your man said and he went to the referee and reported him. Your man got banned then for a year from football. So they took action.

“I was never going to tell the referee, because I didn’t have that kind of confidence. I was delighted that guy spoke up. I was very grateful to him. That was very good of him.”

At the time, Franz didn’t tell anyone, which he says looking back now he wouldn’t advise. If any player was to experience similar abuse, he would advise them to tell an adult, particularly the referee or their manager. Striking back, he says, is not the answer and is never something he considered.

Outside of football, there have been a few incidents through Franz’s part-time job in the local shop.

“It happened a few times, people were kind of asking me, ‘Where are you from?’ They’d be curious; my name’s German, I’m black and I’m living in Ireland, so fair enough people are curious.

“They’d be like, ‘Where are you from?’ I’d be like, ‘I’ve lived here all my life, but my parents are from so and so.’ They’d be like, ‘Were you born here?’ I’d be like, ‘I was born in Tralee.’ They think I’m messing around or whatever, which is all right, fair enough, but that’s kind of ignorance.

“Then there was this one woman. She came in and was like, ‘How’s the coronavirus in your country?’ I was like, ‘Sure this is my country.’ Then she was like, ‘But no, I mean your home country.’ I was like, ‘Sure I was born here. I was only born in Tralee.’

“She wouldn’t let it go basically and she kept asking me. I was only trying to be honest, but I knew what she was looking for. She was obviously asking about Ghana.”

Up until last summer, Franz hadn’t really discussed these incidents with anyone. But in the height of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement last June, he was inspired by other another footballer from Tralee, Stefan Okunbor, who now plays with the Australian Football League (AFL), to share his story through an Instagram post.

Putting up the post was a nerve wracking experience for Franz, but he received “insane” support from the locality. Up to this point his parents weren’t aware of what he had experienced.

“Arrah, they were kind of upset that I didn’t tell them, but they understood. They just said they were sorry for me having to going through that.”

For Franz, the purpose of the post was to highlight that racism does exist in Irish society.

“That’s basically the point, that you can’t just brush it over and say it’s only happening in America, that we’re fine here. It happens here, even if it’s not as evident, it could just be ignorant racism. There isn’t as much physical, but still, it’s all racism at the end of the day. It’s important to get the message out there.”

Looking to the future

After finishing his degree, Franz wants to take a year out and go to Australia with his girlfriend, whenever travel is possible again. He has his sights set on teaching after that, hoping to do a master’s in education when he returns.

He’s not quite sure just yet whether he’ll go towards teaching Irish and geography at second level or primary school teaching. Even if he does go into primary, Franz would like to teach through Irish.

On the subject of Gaeilge, I ask, as a young person growing up in the Gaeltacht does he think there’s a future for the language?

“I definitely think so,” he replies. “I’m not sure will it spread to the rest of the country, but I’d say in the Gaeltachts it’ll stay strong. People are still coming here for Irish college during the summer, so that’d keep it going. Teaching [Irish] in schools is very important,” Franz feels.

“If an older fella came into the shop, you’d speak Irish to him and he’d be delighted to hear you speaking it. That brings a bit of joy. Or even in the pubs, most of the bartenders would be speaking Irish to you and you’d speak Irish back to them. They’d have respect for you in a sense.”

Throughout our chat Franz references the strong sense of community in the local area, whether that be demonstrated through language, sport or other things.

“The really good thing about football is, it brings everyone together. It’s a really close community around here, like I said. Everybody knows each other. Everyone will help you.”

Coming away from the marina and bidding “slán” to Franz, I have a feeling that both Gaeilge and football are in safe hands around here, as well as acceptance and bravery – bravery to stand up and be counted to make the world a better place.

Sheltering at the side of the Dingle marina from a blustery but bright spring day, Franz Sauerland tells me he lives just 15 minutes away, in Ballyferriter.

Feeling confident (without reason), I attempt to say the place name as Gaeilge. The second the words come out of my mouth, I know they sound wrong.

I ask Franz to pronounce it properly: “Baile an Fheirtéaraigh,” he says and I repeat it back.

Later in the interview I say the name of his former secondary school with more conviction: “Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne. Did I say that one better?”

Although he has a true love for GAA, Franz speaks about some racial abuse he has experienced on the pitch. \ Philip Doyle

“You had that one perfect,” Franz says with a kind smile.

When you’re on the “cúpla focal” level and interviewing a Gaeilgeoir, it can sometimes be best to stick to the Béarla, for fear of making a show of yourself. But this was definitely a positive learning experience in the mother tongue.

Franz is a 20-year-old Gaeilgeoir, Gaelic footballer and college student, from, as he said prior to the Irish lesson, Ballyferriter on the Dingle Peninsula. He plays senior club football with An Gaeltacht, as does his older brother, and he’s in the final year of a degree in Irish and Geography in University College Cork (UCC).

Sitting in the town where Franz went to secondary school, the conversation flows through many things. We discuss his love of Gaeilge and football. We also chat about the strong sense of community in and around the Dingle area. Too, we get onto more serious topics; the racism Franz has unfortunately experienced because of the colour of his skin.

Getting to grips with Gaeilge

Franz’s father is German and his mother is Ghanaian, and so, he himself is fluent in three languages; Irish, English and German.

“My father, he was in Germany all his life, but he had business in Ghana and that’s how he met my mother. They came here a year before I was born,” Franz explains.

In 2016-2017 Franz was on the Kerry minor team and he also he captained his school’s under-16 and a half team to an All-Ireland. \ Philip Doyle

“I’ve one brother and two younger sisters. The oldest one of the girls is 12, the other one is nine. My brother, he’s two years older than myself. He lived in Ghana for a year. Then they came here and have been here ever since.”

Growing up in the Dingle Gaeltacht, from naíonra (pre-school) through to primary and secondary, education is all as Gaeilge, and so that’s where Franz learned his Irish. Primary school, for Franz, although not a bad experience, was slightly tougher than secondary school.

“I suppose I didn’t know any different, but I always knew I stuck out a bit because of my colour. They made me feel very comfortable though. All the parents now, they’d all be speaking Irish. My mother would be getting texts from the school through Irish. She’d be asking me to translate even though I was only young. I didn’t know everything,” Franz says.

“I found it a bit tougher than secondary school, because I’d made friends by secondary school. Secondary school was a bit different. I’d made a bit of a name for myself through football. Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne, it’s a great school. I’d almost say I miss it. I had a great six years there. I wouldn’t change it for the world, really.”

Racism in football and beyond

At the age of six, Franz started playing football.

“My friends had been playing. They said come along and I asked my mother if I could go. I remember training used to be every Friday at 6pm. I’d always look forward to it every week,” Franz recalls. “I stuck with it, because I’d say I was fairly good at it. I really enjoyed playing, so I just stuck with it and I’m still playing away.”

In 2016-2017 Franz was on the Kerry minor team. In Pobailscoil Chorca Dhuibhne, he captained the under-16 and a half team to an All-Ireland. The following year, sixth year, he was the captain of school’s successful senior team in the Corn Uí Mhuirí. They got to the All-Ireland semi-final that year.

Despite the fond memories Franz has of playing football, and more still to be made, there are also some tough times associated with the sport. Over the years Franz has faced racial abuse while playing. Discussing these incidents, Franz is exceptionally measured, coming across far more mature than his 20 years.

“I wouldn’t say I experienced too much abuse, but it was fairly evident a few times. Even when I was younger, in the younger blitzes, it wouldn’t be coming from the players even, just the parents. I wouldn’t even say it was ignorance. It was more jealousy. I’d be a bit better than their son or something like that.

“They’d be telling me to ‘go play soccer’, that kind of stuff. It might not sound racist, but you can see the way it is [meant]. I know they may not have any cruel intentions, but I’ll never forget it like. That would force some people to give up the sport almost, because they’d be listening to the older people and think, he knows better than I do.”

There was one other incident where a player racially abused Franz. It was at an under 16 club match. Franz wasn’t playing due to injury, but ran onto the pitch to give a teammate water. This particular player, Franz recalls, was quite angry throughout the game.

“He was giving people abuse the whole game, hitting people and all that. He told me to ‘go back to my cotton fields’. That was really the main one I will never forget, that day. I remember just being depressed going home.

“One of the umpires, he was on their team actually, but he was injured as well. He messaged me that night on Facebook – he somehow knew who I was – saying he heard what your man said and he went to the referee and reported him. Your man got banned then for a year from football. So they took action.

“I was never going to tell the referee, because I didn’t have that kind of confidence. I was delighted that guy spoke up. I was very grateful to him. That was very good of him.”

At the time, Franz didn’t tell anyone, which he says looking back now he wouldn’t advise. If any player was to experience similar abuse, he would advise them to tell an adult, particularly the referee or their manager. Striking back, he says, is not the answer and is never something he considered.

Outside of football, there have been a few incidents through Franz’s part-time job in the local shop.

“It happened a few times, people were kind of asking me, ‘Where are you from?’ They’d be curious; my name’s German, I’m black and I’m living in Ireland, so fair enough people are curious.

“They’d be like, ‘Where are you from?’ I’d be like, ‘I’ve lived here all my life, but my parents are from so and so.’ They’d be like, ‘Were you born here?’ I’d be like, ‘I was born in Tralee.’ They think I’m messing around or whatever, which is all right, fair enough, but that’s kind of ignorance.

“Then there was this one woman. She came in and was like, ‘How’s the coronavirus in your country?’ I was like, ‘Sure this is my country.’ Then she was like, ‘But no, I mean your home country.’ I was like, ‘Sure I was born here. I was only born in Tralee.’

“She wouldn’t let it go basically and she kept asking me. I was only trying to be honest, but I knew what she was looking for. She was obviously asking about Ghana.”

Up until last summer, Franz hadn’t really discussed these incidents with anyone. But in the height of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement last June, he was inspired by other another footballer from Tralee, Stefan Okunbor, who now plays with the Australian Football League (AFL), to share his story through an Instagram post.

Putting up the post was a nerve wracking experience for Franz, but he received “insane” support from the locality. Up to this point his parents weren’t aware of what he had experienced.

“Arrah, they were kind of upset that I didn’t tell them, but they understood. They just said they were sorry for me having to going through that.”

For Franz, the purpose of the post was to highlight that racism does exist in Irish society.

“That’s basically the point, that you can’t just brush it over and say it’s only happening in America, that we’re fine here. It happens here, even if it’s not as evident, it could just be ignorant racism. There isn’t as much physical, but still, it’s all racism at the end of the day. It’s important to get the message out there.”

Looking to the future

After finishing his degree, Franz wants to take a year out and go to Australia with his girlfriend, whenever travel is possible again. He has his sights set on teaching after that, hoping to do a master’s in education when he returns.

He’s not quite sure just yet whether he’ll go towards teaching Irish and geography at second level or primary school teaching. Even if he does go into primary, Franz would like to teach through Irish.

On the subject of Gaeilge, I ask, as a young person growing up in the Gaeltacht does he think there’s a future for the language?

“I definitely think so,” he replies. “I’m not sure will it spread to the rest of the country, but I’d say in the Gaeltachts it’ll stay strong. People are still coming here for Irish college during the summer, so that’d keep it going. Teaching [Irish] in schools is very important,” Franz feels.

“If an older fella came into the shop, you’d speak Irish to him and he’d be delighted to hear you speaking it. That brings a bit of joy. Or even in the pubs, most of the bartenders would be speaking Irish to you and you’d speak Irish back to them. They’d have respect for you in a sense.”

Throughout our chat Franz references the strong sense of community in the local area, whether that be demonstrated through language, sport or other things.

“The really good thing about football is, it brings everyone together. It’s a really close community around here, like I said. Everybody knows each other. Everyone will help you.”

Coming away from the marina and bidding “slán” to Franz, I have a feeling that both Gaeilge and football are in safe hands around here, as well as acceptance and bravery – bravery to stand up and be counted to make the world a better place.

SHARING OPTIONS