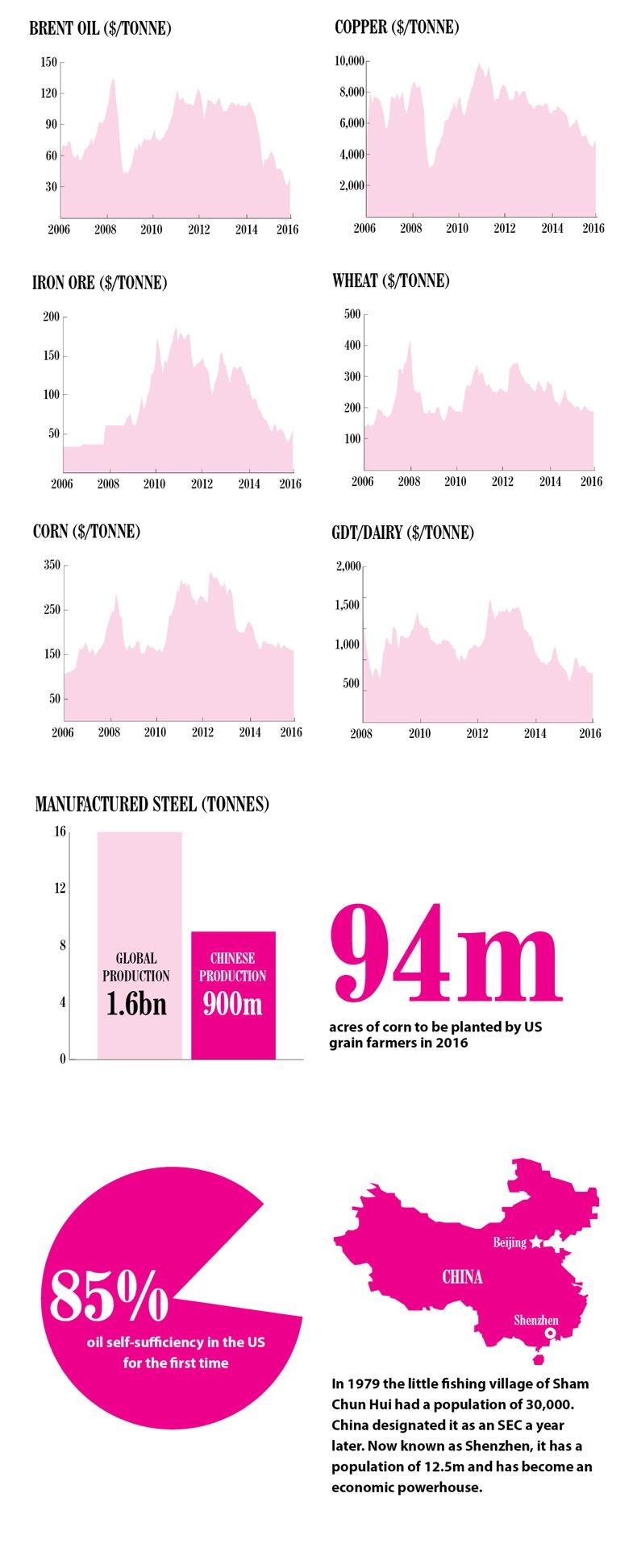

From the late 1990s until the 2008 financial crisis, most commodities experienced double-digit annual real-price growth, a period known as the commodity “supercycle”. The price of oil rose 1,062%, copper rose 487% and corn rose 240% as growing emerging market demand finally caught up with years of underinvestment in various commodity markets.

Not so long ago, a “peak everything” situation was predicted to arise, where it no longer mattered whether the growth curve was rising or falling and that severe shortages were expected in a wide range of commodities. This supercycle was not driven by exploding demand growth, but by supply constraints, such as weather events affecting the yield of corn or soyabean.

So why do commodity cycles exist? Simply put, it takes time. It takes roughly 15 to 20 years to construct an aluminium smelter, and get it up and running, or to dig and develop a potash, copper or gold mine and then extract, refine, and market the ore.

Similarly, oil rigs require years of exploration before any drilling actually occurs. Even then, drilling typically takes place once prices have begun to rally, which incentivises producers to increase output. Interestingly, it may now be oil demand, rather than oil production, which has peaked and will decline, particularly now that shale has emerged as an additional viable source of supply.

Furthermore, with commodities largely priced in dollars, a stronger dollar depresses those prices, which is particularly true for commodities with large production costs in non-dollar currencies.

Record levels

Global stocks of oil reached record levels in excess of 3bn barrels in the last year, according to the International Energy Agency, while the US department of agriculture cannot put an accurate figure on the amount of grain it thinks US grain farmers may have stored away in silos.

Unfortunately, this expanded global capacity has come online at a time when demand growth from emerging markets is waning, particularly from China.

While the Russian and Brazilian economies (two emerging countries that have helped power global economic growth in recent years) are now in recession, China is still growing economically, albeit at a lower level.

Transitioning

From the outside, it may seem like China is in crisis, but what is actually occurring is a transitioning of the Chinese economy.

The Chinese economy is moving away from one of heavy infrastructural investment that has facilitated its demand for steel, copper, iron ore and other raw materials to an economy of greater domestic consumption. The economy in China is evolving and its needs are changing.

This economic evolution is very much part of a greater strategy from Beijing, which is to move towards a domestically focused economy. More than ever, its policies will always be in the interests of China at the expense of western commodity producers.

For instance, China’s manufacturing industry is now moving from simply assembling a series of components produced in other countries to be exported again to a manufacturing sector where more finished products are created from scratch.

On top of this, China has itself now become a major exporter of commodities such as steel and aluminium. Steel prices have plummeted in the last 18 months as exports of Chinese manufactured steel (China manufactures roughly half the 1.6bn tonnes of steel produced annually) doubled to almost 90m tonnes and flooded international markets to create a supply glut.

Strengthening of the dollar

While demand for global commodities has wavered since peak prices in 2011, the final nail in the coffin of the commodity supercycle was hammered in last December, when the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates for the first time in almost a decade.

Despite only a marginal increase, with rates moving 25 basis points to a range between 0.25% and 0.5%, this switch to a tightening fiscal policy has served to send the value of the US dollar soaring in the last 18 months.

Since June 2015, the signs of a lift in US interest rates before the end of 2015 were carefully marked out by Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen. As a result, a bullish US dollar appreciated by almost 25% against a basket of currencies in the last year, as markets prepared for a return to positive interests rates in the US once again.The appreciating dollar and the increase in interest rates only added to the woes of global commodity markets.

Firstly, the impact of this lift in interest rates helped push investors away from commodities and into paper assets, such as bonds.

Secondly, with most commodities priced in dollars, the surge in the currency’s value affected the purchasing power of global commodities buyers and further dragged on commodity prices. We have seen how US grain exports have been significantly dampened due to the bullish dollar this year. The weak export data reported on a weekly basis then only serves to weigh further on grain prices.

Relative costs of production

And finally, with many commodity firms operating in emerging economies, the costs of production – be it drilling for oil, exploring for gas, producing metal or harvesting grain – in local currencies will fall relative to sales in US dollars. This has the effect of keeping previously unprofitable commodity producers in business and helps maintain the supply glut in global stocks.

In Russia, despite the collapse in oil prices, producers increased output and reported strong profits last year thanks to the weakness of the Russian ruble, which has almost halved in value against the US dollar in the past two years.

Similarly, Brazilian grain farmers are also enjoying the tailwinds of a weak domestic currency despite global prices for wheat, corn and soya all being on the floor compared with this time two years ago. The Brazilian real has plunged almost 40% in value against the dollar in the last two years as the Brazilian economy entered recession.

Despite the fall in global grain prices, Brazilian growers are still making a return on their crops as any grain exports from Brazil are traded in dollars. So there is no incentive for farmers to cut sowings in one of the world’s largest grain-producing regions.

In an era of low grain prices, a reduction in crop sowings would be expected from US grain farmers or certainly a move into different, more profitable crops right now.

However, a recent survey by the USDA showed that US grain farmers intend to plant almost 94m acres of corn this year – the third highest planted area since World War II. The attitude of US growers appears to be plant corn and plenty of it with prices so low.

To read the full Agribusiness report, click here.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: