The concentration of power in the Irish meat industry is stark. On the selling side, 60,000 farmers sold 1.5 million cattle in 2013, an average of just 25 each. Only 246 farmers sold 500 cattle or more.

While there are 30 private factories, the real concentration is in the top three players of Dawn, Kepak and ABP, who kill 55-60% of the cattle, while the next three down account for another 20%. It leaves the majority of farmers in a weak position when selling cattle.

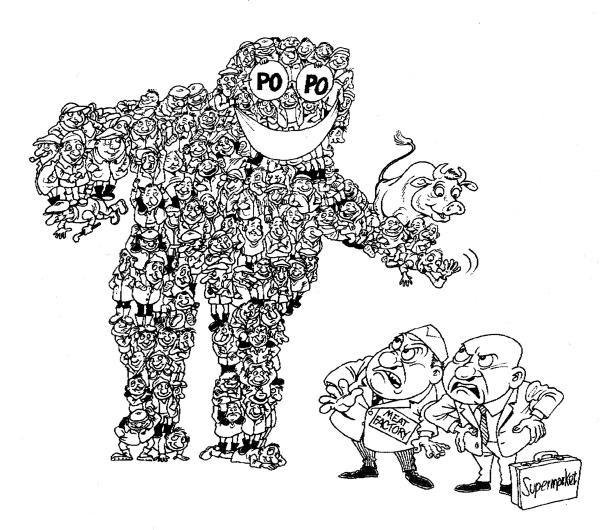

The big question is whether farmers would be in a better position by coming together to negotiate a higher price.

Minister for Agriculture Simon Coveney certainly believes so.

“We would like to set up producer organisations which would be legal entities, professionally run, representing 5,000, 7,000 or 10,000 beef farmers,” the Minister said in the recent Dáil debate on the beef crisis.

Producer organisations (POs) have been held up as the answer for beef farmers, but what are they and can they really become reality? Or is the Minster simply deflecting the problem of the poor profitability in beef finishing back at farmers’ gates?

The recent changes to POs under CAP reform allows countries to legislate more freely. The Department of Agriculture had been drawing up a statutory instrument to provide a legal basis for POs in the dairy sector. The beef crisis has seen them now include the beef sector to give POs more power in Ireland.

More than 15 submissions were made in the public consultation by industry and organisations including Teagasc, Bord Bia, the IFA, ICOS and Meat Industry Ireland.

However, while governments can create the environment, POs must be formed on the initiative of the producers.

What are POs?

Producer organisations are groups of farmers who come together under a formal structure to collaborate on a range of different issues, not just on price. Farmers have proved they can do this in the past through co-ops. POs are similar, in ways, to co-ops, although some argue that they could work against existing co-ops, particularly in dairying.

The EU has always been a fan of farmers working together in this way, bringing in numerous regulations, not just under CAP but also under the Common Fisheries Policy.

Change

The main change in the recent CAP reform from the current regime is that POs will be allowed more scope in relation to competition rules when it comes to negotiating together. The main role of POs is clearly set down in the EU regulations. They must carry out at least one activity from a list that includes:

Joint distribution, including selling.Coming together to promote their products.Joint organising of quality control.The use of common equipment or storage facilities.Joint management of waste directly related to the production of live cattle.Buying inputs in a group.Looking at the list of activities, you could argue that areas like promoting product or quality control are carried out by Bord Bia on quality assurance and promotion, or Teagasc through research and advisory.

It would certainly not make sense for POs to attempt to duplicate similar work in the short term.

However, if POs grow, it may be effective to undertake other specific work which will support the members and produce of the PO.

The main role farmers would expect POs in Ireland to play would definitely be coming together to sell to get a better price. They could also look at the power of buying inputs as well, a role some purchasing groups are already doing on a small scale around the country.

Increasing the bargaining power and delivering a more efficient and cost-effective service in selling and transportation are the main benefits. Some lamb producers and a small number of beef producer groups are already in place.

However, the scale of what the Minister is talking about is a whole new level and will need a professional infrastructure. The new option to provide funding under Pillar II has to be looked at for this. Of course there will be resistance from the factories and the supermarkets to maintain the status quo. It may not all be negative for them, however.

Putting in place contracts with POs could reduce procurement costs and deliver a more predictable supply of quality animals to a pre-determined specification all-year round.

Processors

This would see benefits for processors and their clients. The rise of POs would undoubtedly see an increase in contracts, as has happened in France.

POs working with contracts can also ensure all-year-round supplies and help reduce overall price volatility.

This would need more market price transparency across the supply chain.

Producer organisations are certainly not new in Ireland. The concept has been put to the Irish test in fisheries, where there are now four large producer organisations, with the oldest one in Dublin established in 1975.

More recently, in 1996, the EU opened the way for the fruit and vegetable industry and, probably more successfully, the mushroom industry.

In 2002 there were 17 POs established, 13 of them in the mushroom category. POs were eligible to some support from the EU and received up to €29.4m up to the end of 2008.

Despite that, numbers fell dramatically, declining to four in 2009: two in mushrooms, one in fruit, and one fruit and vegetables. One reason for the demise was the consolidation of the industry.

Demise

Another key reason given was that when the PO scheme was introduced, the Irish retail trade was already dominated by the supermarket chains and multiples. It was difficult for the new POs to break into the marketing chain – a challenge beef farmers will also surely face.

Despite the issues, the report felt that POs have a role for growers to achieve greater bargaining power in the marketplace by becoming part of a larger buying group for inputs as well as a supply base for outputs.

The concentration of power in the Irish meat industry is stark. On the selling side, 60,000 farmers sold 1.5 million cattle in 2013, an average of just 25 each. Only 246 farmers sold 500 cattle or more.

While there are 30 private factories, the real concentration is in the top three players of Dawn, Kepak and ABP, who kill 55-60% of the cattle, while the next three down account for another 20%. It leaves the majority of farmers in a weak position when selling cattle.

The big question is whether farmers would be in a better position by coming together to negotiate a higher price.

Minister for Agriculture Simon Coveney certainly believes so.

“We would like to set up producer organisations which would be legal entities, professionally run, representing 5,000, 7,000 or 10,000 beef farmers,” the Minister said in the recent Dáil debate on the beef crisis.

Producer organisations (POs) have been held up as the answer for beef farmers, but what are they and can they really become reality? Or is the Minster simply deflecting the problem of the poor profitability in beef finishing back at farmers’ gates?

The recent changes to POs under CAP reform allows countries to legislate more freely. The Department of Agriculture had been drawing up a statutory instrument to provide a legal basis for POs in the dairy sector. The beef crisis has seen them now include the beef sector to give POs more power in Ireland.

More than 15 submissions were made in the public consultation by industry and organisations including Teagasc, Bord Bia, the IFA, ICOS and Meat Industry Ireland.

However, while governments can create the environment, POs must be formed on the initiative of the producers.

What are POs?

Producer organisations are groups of farmers who come together under a formal structure to collaborate on a range of different issues, not just on price. Farmers have proved they can do this in the past through co-ops. POs are similar, in ways, to co-ops, although some argue that they could work against existing co-ops, particularly in dairying.

The EU has always been a fan of farmers working together in this way, bringing in numerous regulations, not just under CAP but also under the Common Fisheries Policy.

Change

The main change in the recent CAP reform from the current regime is that POs will be allowed more scope in relation to competition rules when it comes to negotiating together. The main role of POs is clearly set down in the EU regulations. They must carry out at least one activity from a list that includes:

Joint distribution, including selling.Coming together to promote their products.Joint organising of quality control.The use of common equipment or storage facilities.Joint management of waste directly related to the production of live cattle.Buying inputs in a group.Looking at the list of activities, you could argue that areas like promoting product or quality control are carried out by Bord Bia on quality assurance and promotion, or Teagasc through research and advisory.

It would certainly not make sense for POs to attempt to duplicate similar work in the short term.

However, if POs grow, it may be effective to undertake other specific work which will support the members and produce of the PO.

The main role farmers would expect POs in Ireland to play would definitely be coming together to sell to get a better price. They could also look at the power of buying inputs as well, a role some purchasing groups are already doing on a small scale around the country.

Increasing the bargaining power and delivering a more efficient and cost-effective service in selling and transportation are the main benefits. Some lamb producers and a small number of beef producer groups are already in place.

However, the scale of what the Minister is talking about is a whole new level and will need a professional infrastructure. The new option to provide funding under Pillar II has to be looked at for this. Of course there will be resistance from the factories and the supermarkets to maintain the status quo. It may not all be negative for them, however.

Putting in place contracts with POs could reduce procurement costs and deliver a more predictable supply of quality animals to a pre-determined specification all-year round.

Processors

This would see benefits for processors and their clients. The rise of POs would undoubtedly see an increase in contracts, as has happened in France.

POs working with contracts can also ensure all-year-round supplies and help reduce overall price volatility.

This would need more market price transparency across the supply chain.

Producer organisations are certainly not new in Ireland. The concept has been put to the Irish test in fisheries, where there are now four large producer organisations, with the oldest one in Dublin established in 1975.

More recently, in 1996, the EU opened the way for the fruit and vegetable industry and, probably more successfully, the mushroom industry.

In 2002 there were 17 POs established, 13 of them in the mushroom category. POs were eligible to some support from the EU and received up to €29.4m up to the end of 2008.

Despite that, numbers fell dramatically, declining to four in 2009: two in mushrooms, one in fruit, and one fruit and vegetables. One reason for the demise was the consolidation of the industry.

Demise

Another key reason given was that when the PO scheme was introduced, the Irish retail trade was already dominated by the supermarket chains and multiples. It was difficult for the new POs to break into the marketing chain – a challenge beef farmers will also surely face.

Despite the issues, the report felt that POs have a role for growers to achieve greater bargaining power in the marketplace by becoming part of a larger buying group for inputs as well as a supply base for outputs.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: