The farmers supplying liquid milk are a special kind of breed. They are the farmers that calve down cows all year round to produce milk 365 days.

They get up on Christmas Day to make sure that you have milk for your cornflakes.

However, the sector has been haemorrhaging farmers. They are turning away from liquid milk in favour of the lower costs, less labour and higher profits in the spring-calving manufacturing milk sector.

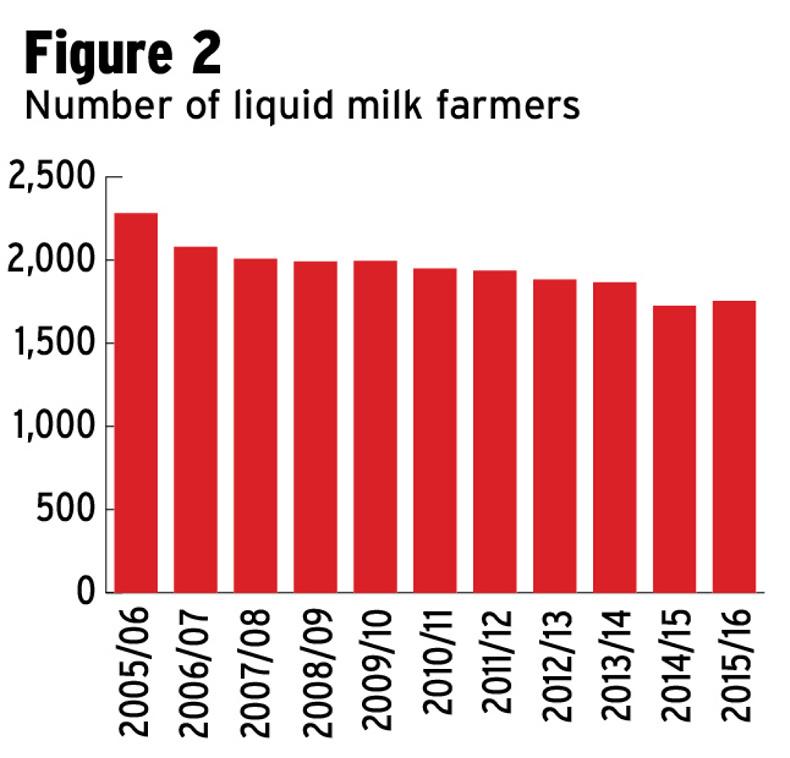

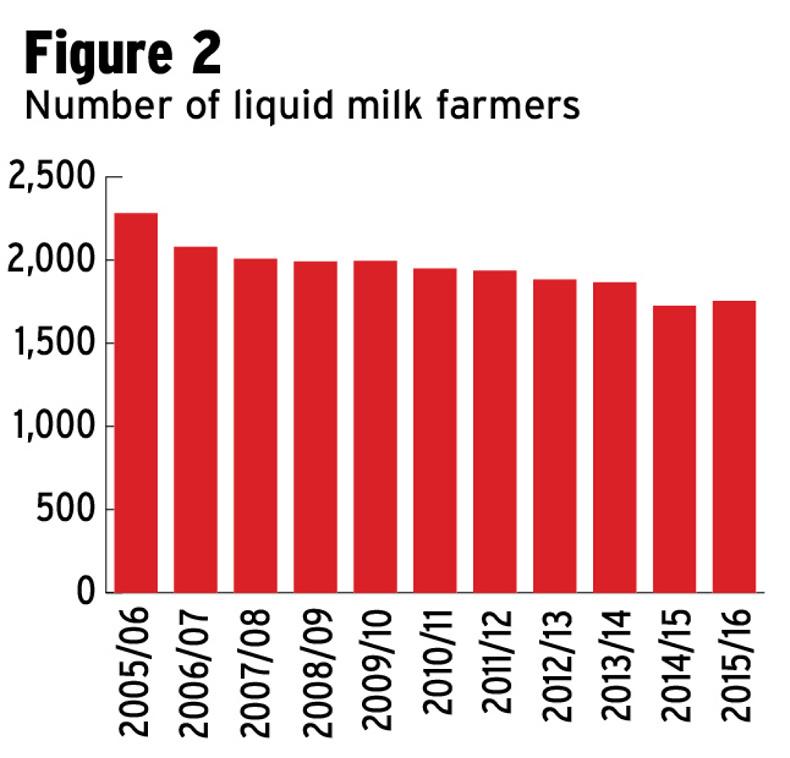

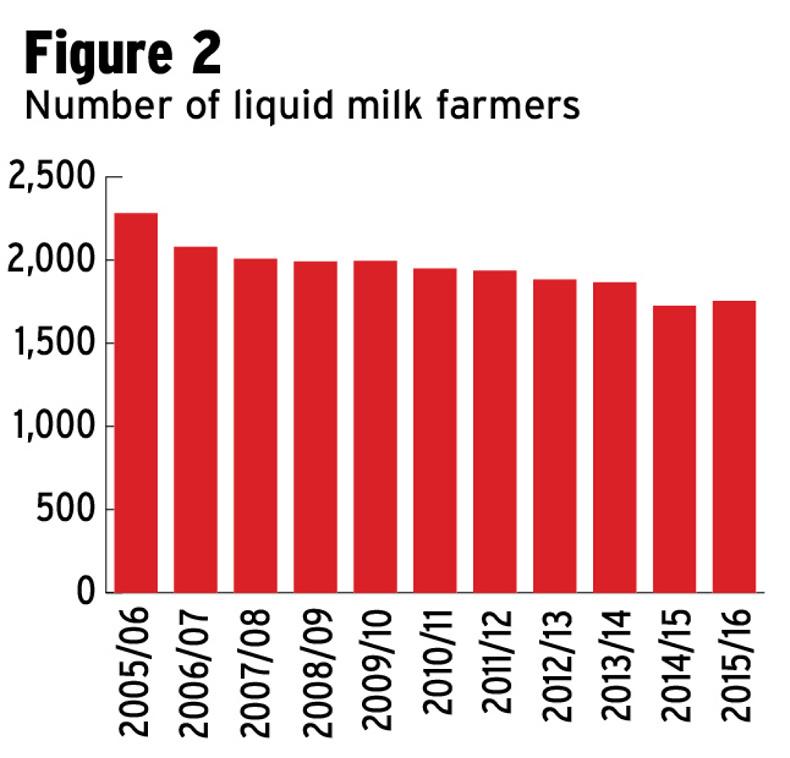

According to the National Milk Agency (NMA) annual report, the number of registered liquid milk producers has been falling steadily since the middle of the 1990s.

In the 1995-1996 milk season, there were 3,344 liquid suppliers. This fell to 2,282 by 2005-2006 and to 1,754 in 2015-2016.

The NMA report showed that those 1,754 suppliers produced a total of 947m litres.

According to Joe Patton of Teagasc, the eminent authority on liquid milk production in Ireland, there will continue to be a natural reduction in supplier numbers as more farms are handed to the next generation.

“The future of the liquid milk sector is dependent on a few things but the big question is if there will be new blood.

“I’m not saying that there will be a mass exodus or anything like that. Each time there is a generational change on a farm, you look at changes. It’s about making changes that will benefit the farm for the next 20 years rather than just doing the same thing,” Patton said.

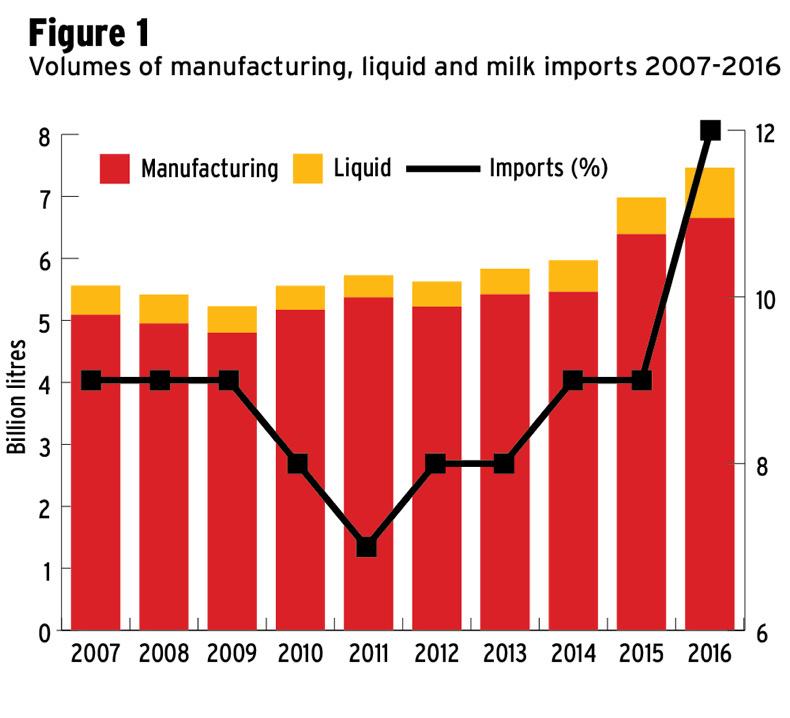

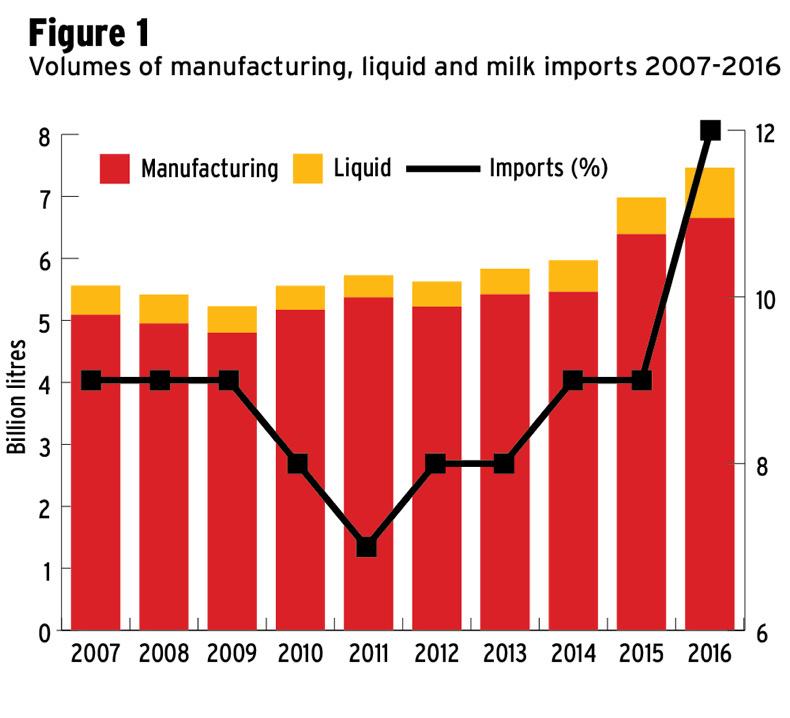

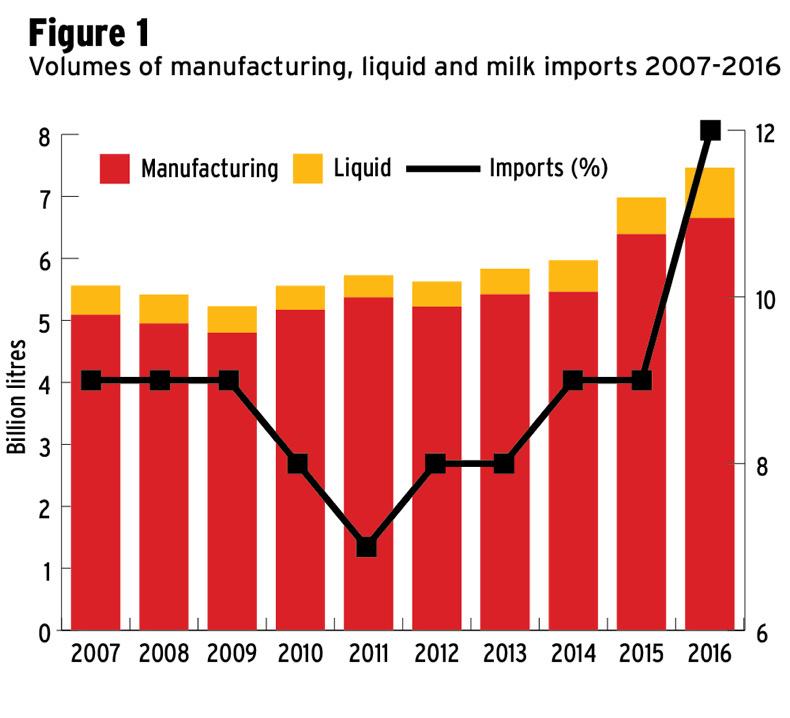

Imports

Total imports of milk into the Republic for processing in 2016 was “the highest on record and amounted to 813m litres”, according to the NMA.

This is an increase of 219m litres, or 37%, on 2015, according the NMA’s annual report for 2016.

All 813m litres imported into the Republic came from Northern Ireland and equated to 37% of all milk produced in Northern Ireland last year.

The large increase is based on Lakeland Dairies’ acquisition of the Fane Valley business, which has seen milk produced in Northern Ireland but processed in Lakeland’s Bailieborough facility in Co Cavan.

While the Fane Valley deal had a lot to do with this growth, liquid milk imports on shelves have been rising, especially alongside the growth of Co Tyrone processor Strathroy. Most of the extra Fane Valley milk will be for processing, not additional liquid milk.

Processing

According to the NMA, there are “three processors with annual supplies in excess of 40m litres of milk for processing for liquid consumption”.

The three big players are Aurivo, Arrabawn and Glanbia. LacPatrick, as well as Clona and Strathroy, also have sections of the market here.

The biggest market for liquid milk is on the retail shelves and competition is stiff.

Glanbia, Arrabawn and Aurivo have been swapping and sharing the multi-million euro Tesco own brand contract in recent years.

With Brexit looming and such a large quantity of milk being imported into the Republic, fears have been raised that there will be difficulties in supplying the domestic market with liquid milk.

Patton does not think that a Brexit scenario would result in a shortage of liquid milk in Ireland.

“Given the scale of the market here, I don’t think we have anything to worry about there.

“The [liquid milk] market is about 550m litres, break that down over 365 days that’s just 1.5 m litres per day. Farmers will produce this provided they are financially rewarded and that contracts are secure.”

By way of context, the large multiples make up the majority of all fresh milk sold in Ireland. Two of the country’s largest retailers account for nearly 50% of all milk sales.

SuperValu and Dunnes have 23% each of all fresh milk sales in Ireland. Tesco and a combination of Aldi and Lidl have 22% each of the market.

Meanwhile, own-label sales account for almost two in every three (64%) of milk sales in retail outlets. Own-label two-litre packs were, on average, 22% cheaper than the main brands.

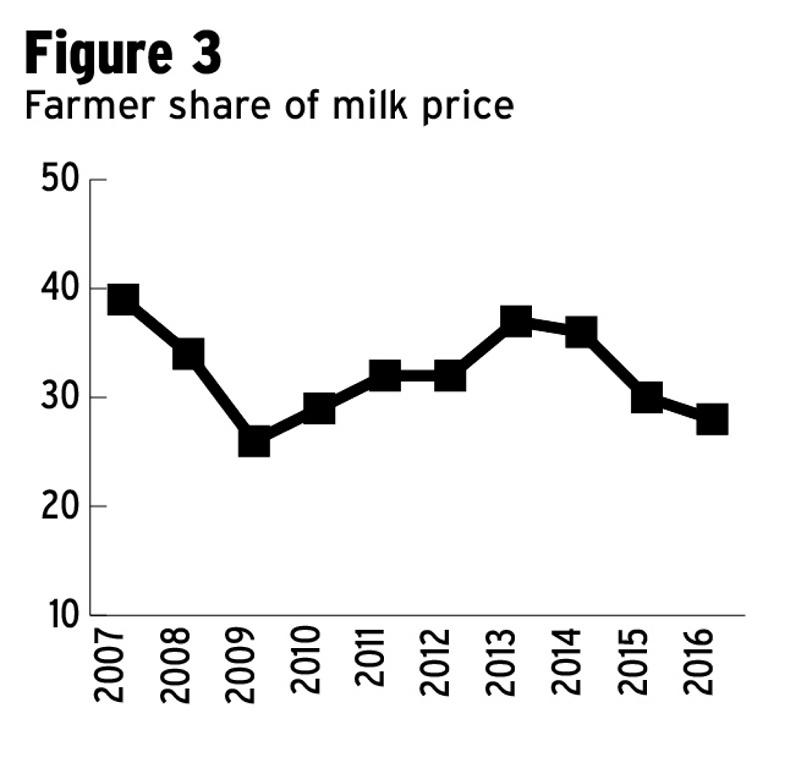

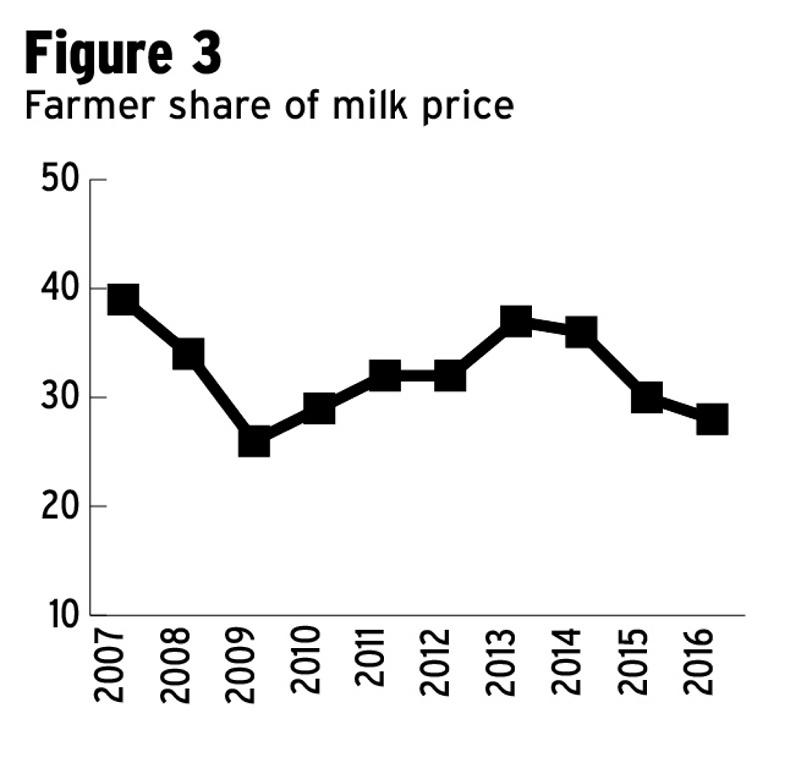

Price squeeze

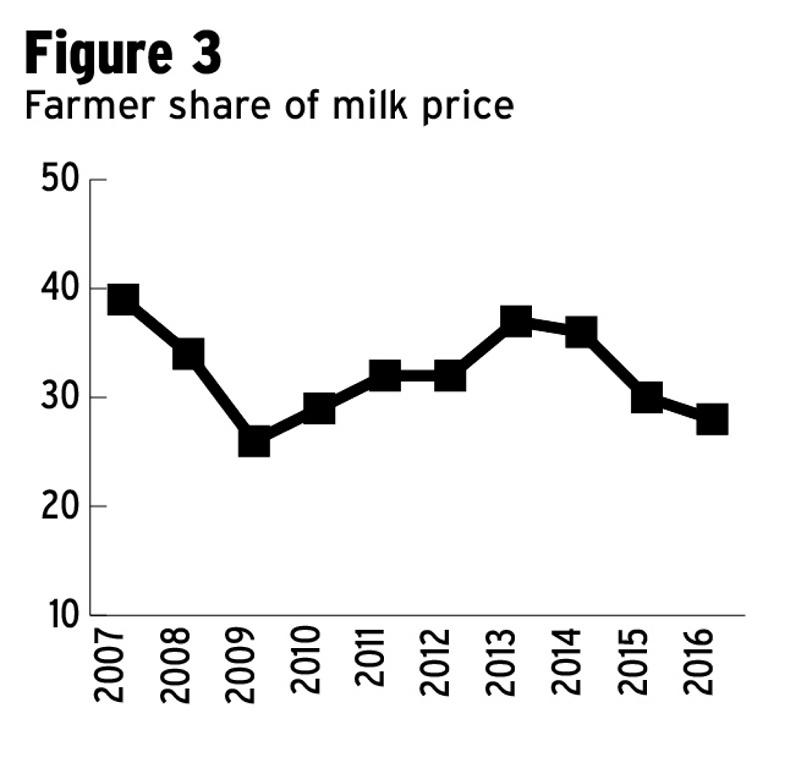

It is the push towards own-brand which has helped contribute to a price squeeze on farmers. The farmer share of the retail price has fallen from 39% in 2007 to 28% last year.

The combination of falling farmer numbers, price cuts and inefficiencies in the sector, on the face of it, paints a bleak picture for the sector.

Not so, according to Patton, who thinks it can be very profitable.

“There are a few things the liquid sector needs to address, in my opinion, to put itself on a stable footing.

“Firstly the inter-generational thing needs to be addressed. If the next generation wants to continue to do liquid milk they need to have facts and figures and central to this is adquate price and a long-term liquid contract.

“Secondly, the liquid sector needs to define good technical principles. Some efficient producers plan calving and breeding dates, calve at two years of age, utilise grass, make good silage and do well out of liquid milk. Then you have others that technically are not up to speed and let calving slip, use breeds and genetics that hit fertility and end up calving all year round,” Patton said.

Clarity

“Finally, there needs to be clarity from processors around the value of off-season milk (winter or liquid). The argument is more winter milk flattens the curve and takes pressure off dryers. Based on Teagasc work, peak capacity and winter supply are related but separate issues.

“Ultimately, the future of the sector will be dictated by farmers sitting down and doing proper figures. Depending on efficiencies, volume produced, price and contract liquid milk can be profitable for those doing it well.”

Read more

Full series: liquid milk

The farmers supplying liquid milk are a special kind of breed. They are the farmers that calve down cows all year round to produce milk 365 days.

They get up on Christmas Day to make sure that you have milk for your cornflakes.

However, the sector has been haemorrhaging farmers. They are turning away from liquid milk in favour of the lower costs, less labour and higher profits in the spring-calving manufacturing milk sector.

According to the National Milk Agency (NMA) annual report, the number of registered liquid milk producers has been falling steadily since the middle of the 1990s.

In the 1995-1996 milk season, there were 3,344 liquid suppliers. This fell to 2,282 by 2005-2006 and to 1,754 in 2015-2016.

The NMA report showed that those 1,754 suppliers produced a total of 947m litres.

According to Joe Patton of Teagasc, the eminent authority on liquid milk production in Ireland, there will continue to be a natural reduction in supplier numbers as more farms are handed to the next generation.

“The future of the liquid milk sector is dependent on a few things but the big question is if there will be new blood.

“I’m not saying that there will be a mass exodus or anything like that. Each time there is a generational change on a farm, you look at changes. It’s about making changes that will benefit the farm for the next 20 years rather than just doing the same thing,” Patton said.

Imports

Total imports of milk into the Republic for processing in 2016 was “the highest on record and amounted to 813m litres”, according to the NMA.

This is an increase of 219m litres, or 37%, on 2015, according the NMA’s annual report for 2016.

All 813m litres imported into the Republic came from Northern Ireland and equated to 37% of all milk produced in Northern Ireland last year.

The large increase is based on Lakeland Dairies’ acquisition of the Fane Valley business, which has seen milk produced in Northern Ireland but processed in Lakeland’s Bailieborough facility in Co Cavan.

While the Fane Valley deal had a lot to do with this growth, liquid milk imports on shelves have been rising, especially alongside the growth of Co Tyrone processor Strathroy. Most of the extra Fane Valley milk will be for processing, not additional liquid milk.

Processing

According to the NMA, there are “three processors with annual supplies in excess of 40m litres of milk for processing for liquid consumption”.

The three big players are Aurivo, Arrabawn and Glanbia. LacPatrick, as well as Clona and Strathroy, also have sections of the market here.

The biggest market for liquid milk is on the retail shelves and competition is stiff.

Glanbia, Arrabawn and Aurivo have been swapping and sharing the multi-million euro Tesco own brand contract in recent years.

With Brexit looming and such a large quantity of milk being imported into the Republic, fears have been raised that there will be difficulties in supplying the domestic market with liquid milk.

Patton does not think that a Brexit scenario would result in a shortage of liquid milk in Ireland.

“Given the scale of the market here, I don’t think we have anything to worry about there.

“The [liquid milk] market is about 550m litres, break that down over 365 days that’s just 1.5 m litres per day. Farmers will produce this provided they are financially rewarded and that contracts are secure.”

By way of context, the large multiples make up the majority of all fresh milk sold in Ireland. Two of the country’s largest retailers account for nearly 50% of all milk sales.

SuperValu and Dunnes have 23% each of all fresh milk sales in Ireland. Tesco and a combination of Aldi and Lidl have 22% each of the market.

Meanwhile, own-label sales account for almost two in every three (64%) of milk sales in retail outlets. Own-label two-litre packs were, on average, 22% cheaper than the main brands.

Price squeeze

It is the push towards own-brand which has helped contribute to a price squeeze on farmers. The farmer share of the retail price has fallen from 39% in 2007 to 28% last year.

The combination of falling farmer numbers, price cuts and inefficiencies in the sector, on the face of it, paints a bleak picture for the sector.

Not so, according to Patton, who thinks it can be very profitable.

“There are a few things the liquid sector needs to address, in my opinion, to put itself on a stable footing.

“Firstly the inter-generational thing needs to be addressed. If the next generation wants to continue to do liquid milk they need to have facts and figures and central to this is adquate price and a long-term liquid contract.

“Secondly, the liquid sector needs to define good technical principles. Some efficient producers plan calving and breeding dates, calve at two years of age, utilise grass, make good silage and do well out of liquid milk. Then you have others that technically are not up to speed and let calving slip, use breeds and genetics that hit fertility and end up calving all year round,” Patton said.

Clarity

“Finally, there needs to be clarity from processors around the value of off-season milk (winter or liquid). The argument is more winter milk flattens the curve and takes pressure off dryers. Based on Teagasc work, peak capacity and winter supply are related but separate issues.

“Ultimately, the future of the sector will be dictated by farmers sitting down and doing proper figures. Depending on efficiencies, volume produced, price and contract liquid milk can be profitable for those doing it well.”

Read more

Full series: liquid milk

SHARING OPTIONS