Here Business editor, Brian Leslie reports on the ABP group at the centre of the horse DNA storm, its founder Larry Goodman and how the revelations may impact on the country’s beef sector.

Ireland’s beef industry has been transformed over the past decade from a frozen commodity-based business dependent on third country sales and intervention to a customer focused business supplying fresh quality assured beef to top retail and food-service customers across Europe.

Irish beef processors have slowly built their reputation across Europe as providers of quality produce but the current horse meat contamination incident and the sensitivity of DNA analysis raises fundamental questions not just for the Irish meat industry but for the meat industry globally.

How all components within the Irish beef sector react to the DNA debacle will ultimately dictate the long term damage, if any, to the overall sector.

Ciaran Fitzgerald, chairman of Meat Industry Ireland said “The Irish beef industry has always been receptive to the concept of continuous improvement, it’s part of the challenge of being an export based business.

“However, the fact is that this issue is a labelling issue and not a food safety issue as certified by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland.

“Before any conclusions are reached we need to establish the source of the ingredient responsible for the 29% result and the sensitivity of such DNA tests and their use within beef/meat categories,” he added

An industry exporting 90% of its product

Ireland produces over 500,000 tonnes of beef annually with 90% of it exported making Ireland the largest exporter of beef in the northern hemisphere and the fifth largest in the world. In 2012, we exported 485,000 tonnes half of which went to the British market with the balance going to continental European.

Ireland has 100,000 beef farmers and a further 10,000 are employed within the sector. Exported beef was worth €1.9 billion to the Irish economy last year.

Irish beef is widely recognised as a premium product across all key markets and , for example, one in five beef burgers eaten in McDonalds across Europe is made from Irish bee.

Britain is our most important export market

The British market is our most important beef export one. A quarter of the beef consumed in Britain is of Irish origin but some 60% of this beef is sold in a mince form.

Of the Irish beef exported to Britain 45% is destined for the retail sector 30% to the food service and 25% for the manufacturing sector

The British market is vital for Irish beef because of its geographic proximity and , more valuable because of the recent fall in the value of the Euro relative to Sterling.

The British do not eat horse meat so this contamination issue is expected to have a negative effect on processed Irish beef.

It may also encourage British retailers to stock British beef first.

Ireland’s uncooked processed beef (frozen beef burgers) is worth almost €200m annually of which €170m was exported in 2012 and again Britain accounted for an estimated 65% of these exports.

Here, Irish consumers spent €23.7m on beef burgers in 2012, €9m on fresh burgers and €14.7m on frozen burgers.

The detection of equine meat in a variety of beef burgers, has been confined to the “economy burgers” sub category.

Total burger production in 2011 amounted to 50,134 tonnes and best estimates suggest the “economy burger” segment accounts for 10% of the total beef burger segment with an annual value of €20m.

The ups and downs of the ABP food group

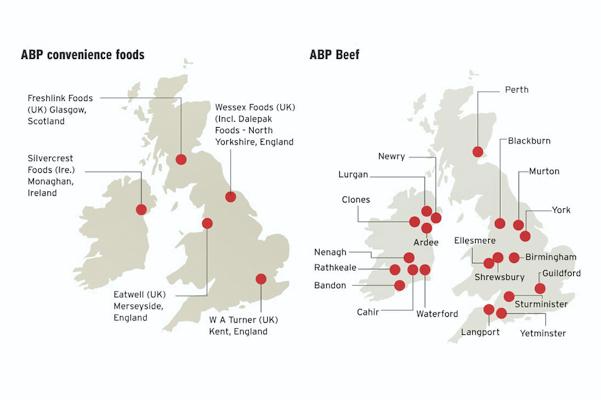

The company at the centre of this horse meat story is Larry Goodman’s ABP Group. Two of its subsidiaries had samples which tested positive for equine and pork meat- Silvercrest Foods in Co Monaghan which produced the burger for Tesco that contained 29% equine meat and its sister plant, Dalepak Foods in England.

ABP’s annual accounts are private but its turnover is reported to have topped €2.2bn last year and its profits were estimated at between €60-€80m. It is said to have 50m customers in Europe for its products on a weekly basis.

ABP continues to grow and continues to diversify.

It expanded its pet food business and opened its first biodiesel plant last year. The company employs 7,500 people in five divisions- Beef, Convenience Foods, Pet Foods, Renewables and Proteins.

ABP has six slaughtering plants in Ireland and kill an estimated 350,000 animals a year in Ireland.

It also has extensive slaughtering capability in Britain and Poland making it Europe’s largest beef processor.

ABP has built its strategy in recent years on offering premium quality products to a growing range of retailers across Britain, Ireland and mainland Europe.

Silvercrest Foods, which suspended its production last week because of the horse DNA issue, accounts for 5% of ABP’s total turnover and has supply contracts with Tesco, Superquin, Dunnes Stores, Aldi, Londis and Burger King in Ireland and with Asda, Sainsbury, Tesco, Morrisons, Waitrose, Iceland and the Coop in Britain.

The horse DNA issue undermines its brand and that of Irish beef in Britain and is likely to lead to a raft of law suits from affected retailers, most notably Tesco.

Industry sources estimate this will cost ABP in excess of €100m over the coming year alone. Some £300m €375m or 1.1% was wiped of the value of Tesco when this story broke last week.

Larry Goodman – the shy tycoon

Media-shy Larry Goodman is ABP’s executive chairman and Ireland’s 15th richest person with a estimated wealth of €745m.

He set off on his business ventures at the age of 16, and purchased his first abattoir in 1966. His company expanded throughout the seventies and eighties slaughtering cattle to go into EU intervention and later he built up extension supply arrangements in the middle East and Russia supported by state export credit guarantees.

The war in Iraq in 1990 led to a default by the Iraqi government on €225m owed to Goodman’s company leaving it with total debts of IR£500m (€635m). The banks “pulled the plug” on Goodman and following emergency legislation the company was put into examinership (a first in Irish history) which offered ABP protection from its creditors.

Goodman was forced to sell his extensive property portfolio.

The subsequent Beef Tribunal highlighted various forms of irregularities within ABP on tax issues, packaging weights and origin stamps but nobody was ever prosecuted on foot of the Tribunal findings.

In 1995, Goodman bought back ABP for €38m with the support of the McCann family and he also bought back much of his former property interests, most notably acquiring full control of the Setanta Centre on Dublin’s Nassau street for €85m in 2003 from packaging tycoon, Michael Smurfit and Scottish entrepreneur Harry Dobson.

Goodman’s extensive property portfolio is held through the Parma Group a family investment holding company with an annual rent roll estimated at between €20m and €30m.

His other interests include the Earl of Kildare hotel in Dublin which he bought for €17m in 2007, a 40% stake in the Galway clinic, a 33% stake in the Hermitage Clinic and a 28% stake in Blackrock Clinic.

Goodman sold his 6% stake in Hilton Foods in 2011.

Late last year, Goodman swooped to purchase the former Bank of Ireland’s head office on Baggot street for €43m and owns extensive land holdings including the 700 acres around his house at Braganstown, Co Louth where they finish 9,000 cattle annually.

Confusion set to continue

Until the source of this horse meat is clarified, confusion will continue within Ireland’s beef industry.

Ireland is one of the first countries to use DNA testing which will certainly advance the level of traceability for products produced from Mechanically Recovered Meat within the food chain for all countries.

However, its practical use and the associated costs need to be worked out.

Meat products are being supplied across Europe at prices where reputable Irish firms just cannot match.

The driver for ever cheaper food throws up real issues- not just farmers, processors and retailers but for consumers and policy makers alike.

With food inflation of just 18.5% from January 2005 to November 2012 when overall consumer prices rose by 37.7%, this at a time when processors and farm input prices increased exponentially tells its own story of the ongoing margin erosion within the sector.

The market reaction to the horse DNA issue remains confined to the British market but all retailers are likely to react with further supplier stipulations.

Industry sources claim that new deals are now being put on hold as retailers and buyers focus on re-checking their suppliers.

The Dioxin scare in 2008 showed us that if this incident is dealt with transparently and swiftly the loss of contracts and markets can be minimal.

SHARING OPTIONS