Gilbert Cosson’s pig and dairy farm, a short drive inland from the coast of Brittany, looks like any other – until you come up close and notice his new wind turbine. This is the first such machine in France made by the Galway-based firm C&F Green Energy, an established manufacturer of turbines in Ireland and Britain.

Cosson, 56, was the ideal candidate to bring Irish-made wind generators to the country after the failure of previous attempts. He already had solar panels installed and is always curious about new technologies.

“I like engineering and understanding how things are made,” he told the Irish Farmers Journal during a recent open day on his farm.

After seeing the turbine at the SPACE show nearby, he said he would buy one if C&F brought him to Ireland to see how they were made.

The company obliged, and the machine was connected to the farm’s electricity mains at the beginning of this year.

Milking robot and pig shed ventilation

This hilly site 20km inland from the sea is well located to get a regular breeze, and Cosson’s farm is ideal to benefit from the resulting steady stream of electricity. He milks 45 cows robotically and finishes 1,500 pigs in ventilated sheds. “I’m consuming at least 10kW at any given time,” he explained. He also keeps 200 sows on an outfarm.

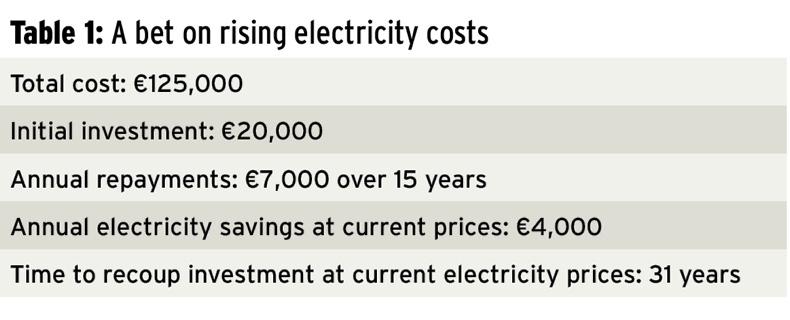

His annual electricity bill is currently €8,000, but he expects this to go up from next year. “This is a long-term bet on rising power costs,” he said.

Cosson built the concrete slab and hut used to house the electrical equipment connected to the turbine. The machine itself, with a capacity of up to 25kW, and other ancillary works cost him €125,000 in total.

One bad surprise was the high cost of the underground cable linking the turbine to the farm buildings, at €8,000.

A local company, Diwatt, managed the whole process, supplying the equipment from Ireland and organising planning permission.

€4,000 annual saving

So far, wind power has been on track to cover half of Cosson’s €8,000 annual electricity bill. Such savings, rather than profit from selling power back to the national grid, is the attraction for French farmers.

“The goal is self-consumption,” said Diwatt head Florian Lucas. Farmers there pay 12c to 14c excluding VAT per kWh for electricity, while the feed-in tariff (FiT) to sell wind power back to the national grid brings in only 8.5c/kWh. The same logic applies in Ireland at the moment, but this could change with new incentives due to encourage renewable energy production next year.

The difference, however, is that electricity charges for small businesses rose by 9.5% in France last year – three times faster than here. And this is only the beginning: “The end of regulated tariffs for small businesses on 1 January 2016 will push electricity prices up,” said Lucas. “This is a good time for farmers to buy equipment.”

He expects a wind turbine to pay for itself within 10 years as a result of rising electricity costs – instead of three decades at current prices in the case of Gilbert Cosson.

High-tech features

To tap this emerging market – and others, such as Japan with its high FiTs or the US where grants are available for investment in wind energy – C&F has developed smaller turbines with the kind of high-tech features usually found in large, industrial units.

The machine installed on Cosson’s farm computes the best angle to catch the wind and rotates automatically, adjusting the angle of its blades in the process. It is connected to a maintenance centre through the mobile phone network. Irish-based technicians monitor it and can stop it if something goes wrong. Yet, it cannot be seen or heard by any neighbours, and Cosson had no problem placing it directly opposite his home.

The machine installed on Cosson’s farm computes the best angle to catch the wind and rotates automatically, adjusting the angle of its blades in the process. It is connected to a maintenance centre through the mobile phone network. Irish-based technicians monitor it and can stop it if something goes wrong. Yet, it cannot be seen or heard by any neighbours, and Cosson had no problem placing it directly opposite his home.

“Our machines are not the megawatt, 80-metre towers you see on TV shows,” C&F’s global operations and business development manager Paul Fitzpatrick told the Irish Farmers Journal. ‘‘Their tip point would be under 50m and a passing car would make more noise than our turbines.”

C&F Green Energy is part of the C&F engineering group based in Athenry, Co Galway. Its range of turbines, starting at €75,000 for a 20kW machine, has proved successful in both Ireland and the UK, where the company claims to have 1,200 of them installed.

It is now competing with European and US-based manufacturers to expand internationally and its foray into the French market is supported by Enterprise Ireland.

“France is a huge agricultural market and with the removal of milk quotas and the expected increase in the cost of electricity, there is a huge opportunity here for C&F,” said Aisling O’Donnell, business development executive for Enterprise Ireland in Paris.

The company’s growth could benefit the Galway area, where it already employs 500 people.

“Everything is manufactured in the west of Ireland,” said Fitzpatrick – although the company is considering sourcing some products in its target markets, such as the masts supporting the turbines.

“You need a balance between the two: to sell in the US, you also need the stamp ‘Made in USA’,” he added.

As for Gilbert Cosson, he is already looking out for the next innovation: batteries to store electricity during high winds and use it later, increasing self-sufficiency. “The Chinese are working on it. I’m sure they will be available in two years’ time’,” he said.

Maintenance contract an essential part of the investment

Gilbert Cosson’s turbine is monitored remotely, self-greasing and attached to an articulated mast that can be lowered for a half-day annual maintenance service.

French distributor and installer Diwatt also provides the maintenance contract – a crucial part of the long-term investment in wind energy.

“We installed a turbine in 2010, but it broke down and the company that sold it to us has shut down,” said one of the farmers who visited Cosson’s farm on the open day.

A group of Scottish farmers recently contacted the Irish Farmers Journal to complain that C&F Green Energy, too, had trouble providing maintenance services there.

According to the turbine owners, they paid upfront for one- or two-year maintenance contracts, with servicing failing to take place in time. They also said that C&F asked to renew maintenance contracts before previously agreed services were completed.

The company acknowledged that there had been delays in servicing in the past because of the sharp increase in the number of turbines being installed, but added that it had contracted a new service provider in the UK more than four months ago, with more people to carry out maintenance visits.

“When you have 1,200 machines in the market, you cannot get to everybody in one day, but to my knowledge there is no conflict at the moment,” said C&F’s Paul Fitzpatrick.

Whatever the make and model chosen when installing a wind turbine, the cases above highlight the need to go through an established local installer to source and service the equipment.

At current electricity prices in France, Gilbert Cosson’s wind turbine would pay for itself in 31 years. To make the investment worthwhile within a more reasonable time frame of 15 years, French electricity prices would have to double. This may seem a lot, but with a near 10% jump in electricity costs for small businesses last year and deregulation on the way, the bet could prove to be a winning one in the long run.

SHARING OPTIONS