The World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreed to abolish subsidies on agricultural exports last week. It has been described as the most significant outcome on agriculture since the WTO was established in 1995. However, many will argue that its significance merely reflects just how ineffective the organisation has been over its 20-year history rather than the significance of the agreement reached.

In recent years, the use of export subsidies has fallen dramatically and, therefore, the financial impact of last week’s deal is likely to be limited. In the case of Europe, export refunds have not been used to any significant level for many years.

With free trade agreements and bilateral negotiations becoming the preferred route for trading blocs to negotiate on market access, there was intense pressure on the WTO to prove it still functions and remains relevant.

We should wait to see to what extent the WTO now disciplines offending regions before drawing conclusions on the significance of last week’s deal. How will the US be disciplined for maintaining its export credit scheme and how will the interest rate support provided by the Brazilians under their export credit scheme be addressed?

Of course, of more relevance to Europe are the thorny issues of market access measures and domestic supports for agricultural products. Both are areas that have caused WTO talks to collapse in the past, most recently when India refused to back a deal unless it included concessions allowing developing countries the freedom to subsidise and stockpile food. WTO rules cap direct production subsidies to farmers in developing countries at 10% of the total value of agricultural production, based on 1986-88 prices.

Tackling export subsidies in isolation without addressing market-distorting domestic supports is a flawed policy. Domestic support measures that underpin production and provide a global competitive advantage have the same effect as export subsidies.

While we wait for the final text around the deal, there appears to be a commitment preventing supports that were traditionally channelled through export refunds being diverted into domestic supports. However, we have seen in the past how major trading blocs have developed elaborate support mechanisms that can operate under the radar of the WTO. An obvious example is the US food-for-schools programme which effectively operates as a market intervention mechanism. It allows the government to intervene in the commodity market during periods of surplus. These products are stored and distributed through the schools programme.

From a European perspective, successive reforms have moved the vast bulk of support measures under the CAP into the WTO acceptable green box. At the same time, the WTO has ignored a reversal of the US Farm Bill. It is now widely accepted, even within the US, that the majority of market support measures under the Farm Bill fall into the amber box category, which are seen as distorting trade.

For the WTO to prove its relevance, it can no longer maintain this position. It must be recognised that, to date, Europe has received limited benefits from the radical reform of the CAP, driven largely by WTO regulations. In the case of Ireland, we see Kerrygold butter continuing to incur significant tariffs on imports into the US while the potential to develop the market for Irish cheddar is hampered through careful quota management measures.

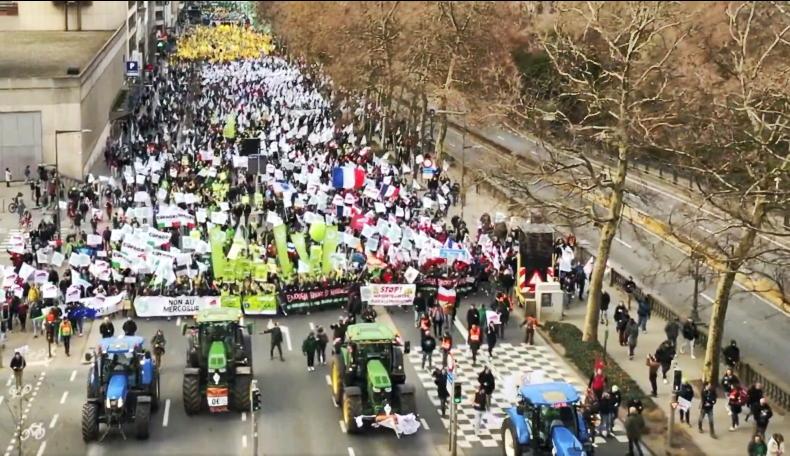

Meanwhile, the reigniting of negotiations with the WTO needs to be taken into consideration in the context of ongoing negotiations between the European Commission and other major trading blocs – primarily the US and Mercosur.

Side deals outside of the WTO should only be advanced where the interests of European agriculture are protected. We cannot allow the interests of European agriculture be sacrificed from both sides while those who ignore WTO regulations and EU production standards prosper.

Listen to markets specialist Phelim O'Neill discuss the latest developments in international trade talks in our podcast below:

SHARING OPTIONS