New research using radiation detection data from sensors mounted to low-flying aircraft has increased the area of Ireland thought to be covered by peaty soils from 24% to 30%.

Lead author of the study, University of Galway’s Dr Dave O’Leary explained that invisible gamma rays released during the natural radioactive decay of materials in rocks and soils were key to identifying peaty soils this way.

“Peat soils have a unique ability to block this type of naturally occurring radiation, drastically reducing the number of gamma rays detected by the sensor mounted on the Tellus aircraft when flying over peat soils.

“There are several sources of this natural radiation in the environment and our study uses the unique relationship between this radiation and peat soils to identify where peat is likely to be present.”

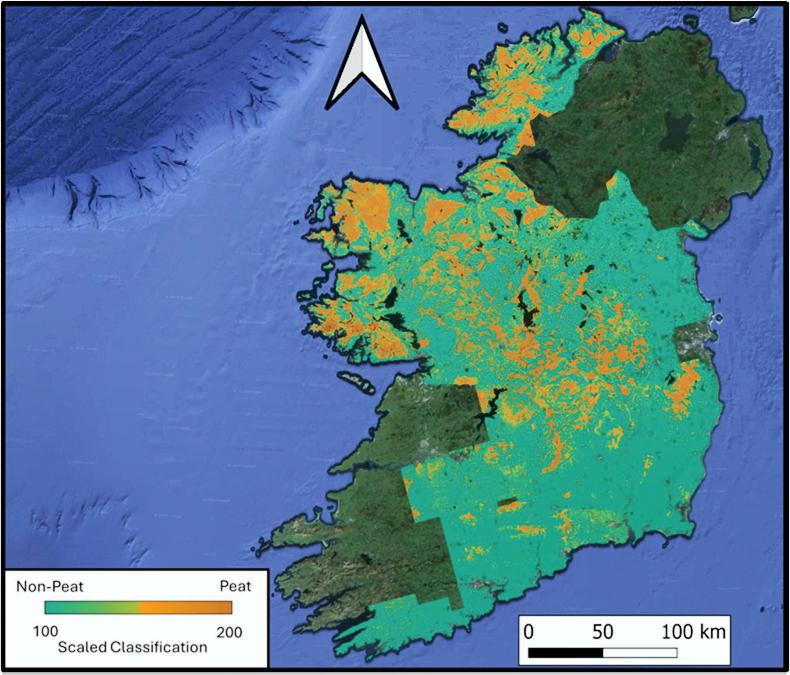

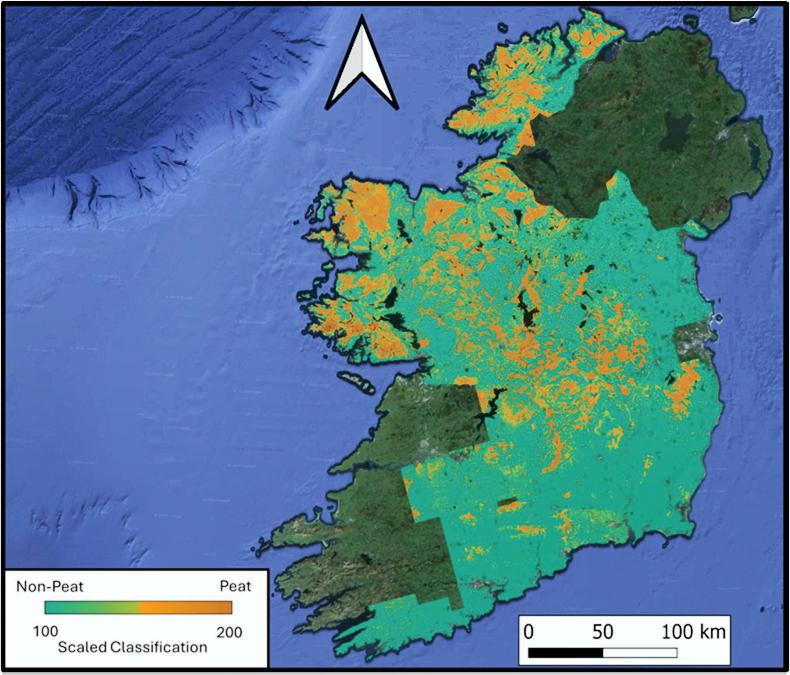

The map produced during the University of Galway study showing 50m by 50m resolution of peat and peat soil transition areas (brown to orange) and mineral soils (green). / Dr Dave O’Leary

The researchers stated that this can allow them to determine the extent of peat soils, but not the depth of peat.

“It also allows them to identify areas where soil changes from peat to mineral, which are typically areas hidden under forests and grasslands,” O’Leary continued.

“Few countries have invested in such an incredible dataset, which puts Ireland at the forefront of peatland mapping research.

“Importantly, the data is free to use. We hope that our research will encourage and incentivise other countries to invest in such surveys to meet their peatland mapping needs.”

The study gives policymakers more accurate data on the location and extent of the country’s peat soils and will help to highlight areas suitable for measures which reduce emissions, according to Dr Eve Daly of the university’s school of natural sciences, who co-led the study.

New research using radiation detection data from sensors mounted to low-flying aircraft has increased the area of Ireland thought to be covered by peaty soils from 24% to 30%.

Lead author of the study, University of Galway’s Dr Dave O’Leary explained that invisible gamma rays released during the natural radioactive decay of materials in rocks and soils were key to identifying peaty soils this way.

“Peat soils have a unique ability to block this type of naturally occurring radiation, drastically reducing the number of gamma rays detected by the sensor mounted on the Tellus aircraft when flying over peat soils.

“There are several sources of this natural radiation in the environment and our study uses the unique relationship between this radiation and peat soils to identify where peat is likely to be present.”

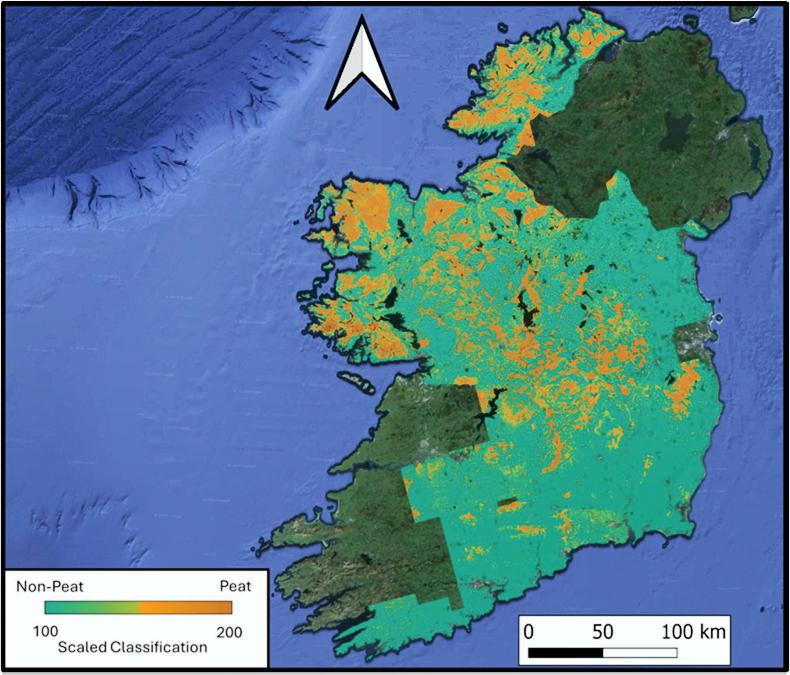

The map produced during the University of Galway study showing 50m by 50m resolution of peat and peat soil transition areas (brown to orange) and mineral soils (green). / Dr Dave O’Leary

The researchers stated that this can allow them to determine the extent of peat soils, but not the depth of peat.

“It also allows them to identify areas where soil changes from peat to mineral, which are typically areas hidden under forests and grasslands,” O’Leary continued.

“Few countries have invested in such an incredible dataset, which puts Ireland at the forefront of peatland mapping research.

“Importantly, the data is free to use. We hope that our research will encourage and incentivise other countries to invest in such surveys to meet their peatland mapping needs.”

The study gives policymakers more accurate data on the location and extent of the country’s peat soils and will help to highlight areas suitable for measures which reduce emissions, according to Dr Eve Daly of the university’s school of natural sciences, who co-led the study.

SHARING OPTIONS