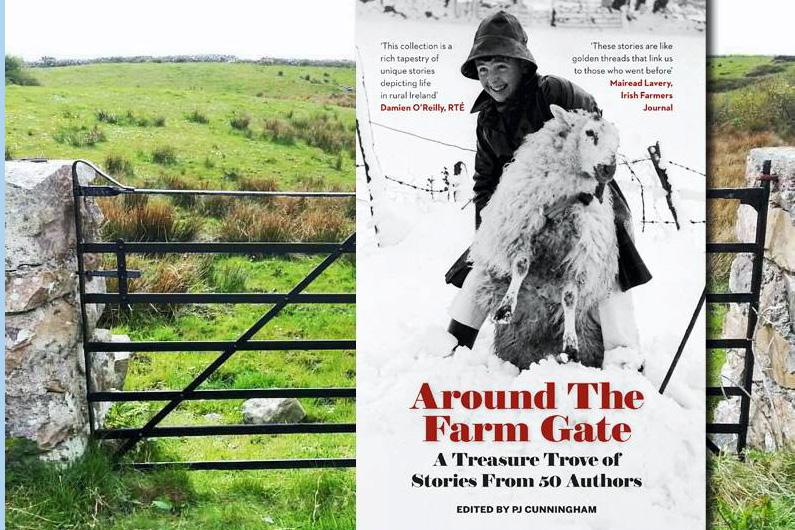

Around The Farm Gate is a unique collection of 50 stories written by different authors detailing their experiences of the rural Ireland in which they grew up.

In a brief snapshot, each story captures the activities of people striving to earn their daily bread in different settings across the country.

This book offers a rare glimpse of our recent history, encapsulating and preserving the traditions of several generations.

The collection is a collaboration between Countrywide (RTE Radio 1), the Irish Farmers Journal and Ballpoint Press Ltd.

Meet the team behind Around The Farm Gate at the National Ploughing Championships:

at 12pm on Tuesday 22 September on the Irish Farmers Journal stand.at 12:30pm on Wednesday 23 September on the RTE stand.The Threshing

by Dan Daly

It was a truly wondrous sight for a four-year-old to behold. The huge lumbering salmon-coloured outline of the threshing machine made its way in the narrow little roadway to the farmyard. It rattled the branches of the ash trees as it rumbled over the gravel. A big faded-red tractor built like an elephant pulled it.

I can’t recall a single one of those September days when the sun didn’t shine on threshing day. The world always seemed warm and yellow. A ‘meitheall’ of neighbours – as many as 10 – had gathered in the yard, and were chatting and watching as Tangney’s towering yellow thresher was manoeuvred into position alongside the ricks of barley that had mellowed and rested in the autumn sunshine for weeks.

The excitement had begun weeks earlier when the reaper ’n’ binder – an exciting sight in itself – had come to cut the barley. I followed it as it slowly cut a swathe through the crackling barley and methodically and regularly kicked out the bound sheaves with a heavy click. My father and a few helpers followed, stooking quietly as they went. The dog ran around excitedly as I dashed from stook to stook. The stubble stung my feet.

Tangneys of Castlemaine threshed from September right through until St. Patrick’s Day and sometimes beyond. They progressed westwards along the Castlemaine-Dingle road on the Dingle Penninsula through Boolteens, Keel, Inch and on as far as Dingle.

To my mind, it appeared to be a magical journey to wonderful places with a fascinating machine. They threshed some of the corn on the westward trip and the remainder on the homeward journey when the grain was well and truly ready. The great threshing odyssey was punctuated with sing-songs and harvest parties and none was as lively as when they reached Dingle.

The big belt was connected from the tractor to the thresher and it soon looped into action. A loud humming noise built up and filled the yard. Mick Enright and my father piked the sheaves from the rick onto the thresher. The twine was cut and the sheaf was fed into the drum. The grain sacks were filled and carried to the shed. The grain felt cool as it poured through my fingers into the sack. At the other end of the thresher, a couple of men heaped the straw onto a new rick.

The oats were always my favourite. Its straw, grain and chaff had a soft, smooth quality. The chaff from the barley used to stick to my clothes and tickle me. I was quickly covered with the stuff. I needed a rest and headed for the kitchen.

The table was laden with food of all sorts. There was white and brown bread, butter, thick slices of ham and brown sauce. Pots sizzled on the cooker. Mother and Mrs. Carroll headed out with mugs of tea and slices of thick currant bread. Bottles of stout were produced. My father wiped the sweat from his forehead and downed one. Chaff and dust danced in the beams of mellow light that shone through the big ash tree in the corner. There was a golden warm atmosphere in the yard.

My father cracked a match and lit a cigarette. “Mind where you throw that match, Paddy,” joked Mick Enright.

“We don’t want a conflagration”, added Pats Shea.

Suddenly my father started jumping up and down on the rick. At the same time Patrick Hickey fumbled in the barley for the fag that had fallen out of his grasp. He threw it into the ditch and stamped on the straw to stifle the flames. It had the makings of a wondrous duet as father then began to twitch and slap his trousers vigorously.

He had the stage and everyone’s attention as he shook, twisted and danced in the manner of an intoxicated Indian high on firewater or a crazed Morris dancer. He shouted something along the lines of “the divil take ya” and fell on his back on the barley. He then sat up. Strands of barley were stuck to his hair. He looked like an agricultural Stan Laurel. The silent bemusement of the onlookers had given way to curious laughter.

“What’s up, Paddy?”

“A bloody mouse ran up the leg of my trousers,” he replied as he looked around.

“And where is he?”

“Devil if I know,” he replied to a burst of laughter as he gave his trousers another slap.

“Here Paddy, put that on your head,” said Jim Cronin, handing him a bottle of stout.

“I think you’ll need something stronger than that,” advised Mick Enright as he headed into the back kitchen. He returned with a bottle of whiskey and a few mugs. He poured Paddy a drink. He swilled it in the mug and savoured a deep draught. He wiped his brow and took another swallow.

“God Paddy, you’d go to any length for a proper drink,” said Pats Shea.

“Well I don’t want to go through that again, the little shagger.”

“Kitty said you can never dance when she’s around.”

“Well here’s to the harvest, Paddy and the mouse!”

They clicked mugs and laughed.

Soon they were back at work. My father now had his trouser legs tied with two pieces of blue binder twine. There was half a rick of barley still to thresh. And when the last sheaf had been tossed and the dust had settled they sat in the shade of the new rick of straw, pulled the heads off a few bottles, passed around the cigarettes and rested. There was a contented silence for a while.

“I wonder is he any relation?” inquired Mick Enright.

“Who?” asked my father.

“The mouse,” he replied.

“What are you on about?”

“I wonder is that mouse any relation to the fellow who started the great Chicago fire?” inquired Mick.

“T’anam don diabhal, that wasn’t a mouse. ‘Twas a cow kicked over Mrs O’Leary’s lamp,” Dad informed him.

“I could have sworn it was a mouse. The memory plays strange tricks. Well it could have been just as serious. As Pats said we could have had a conflagration.”

“The divil take him.”

There was a contented chuckle.

The yard was suffused with a gentle, golden glow. The rick of straw had risen to touch the lowest branches and was having the finishing touches applied. The bags of barley were stacked high in the shed.

They chatted and joked for a while and then answered the call to head in for supper. Soon Tangneys and their enchanting machine departed, rattling the ash branches as they went. They left a void and a mound of chaff.

I felt a little sadness as the neighbours vanished into the evening, their names echoing in farewell. There was a strange silence in the yard – not even a rustle. Beyond the yellow rick, through the great ash tree, I could see the setting sun, large and golden, ripening Slieve Mish’s heather to a flaxen bloom.

Dan Daly is a native of Kerry but lives in Robinstown, Navan, Co Meath. A recently retired primary school principal, he is married with three children. He writes as a hobby.

Around The Farm Gate is a unique collection of 50 stories written by different authors detailing their experiences of the rural Ireland in which they grew up.

In a brief snapshot, each story captures the activities of people striving to earn their daily bread in different settings across the country.

This book offers a rare glimpse of our recent history, encapsulating and preserving the traditions of several generations.

The collection is a collaboration between Countrywide (RTE Radio 1), the Irish Farmers Journal and Ballpoint Press Ltd.

Meet the team behind Around The Farm Gate at the National Ploughing Championships:

at 12pm on Tuesday 22 September on the Irish Farmers Journal stand.at 12:30pm on Wednesday 23 September on the RTE stand.The Threshing

by Dan Daly

It was a truly wondrous sight for a four-year-old to behold. The huge lumbering salmon-coloured outline of the threshing machine made its way in the narrow little roadway to the farmyard. It rattled the branches of the ash trees as it rumbled over the gravel. A big faded-red tractor built like an elephant pulled it.

I can’t recall a single one of those September days when the sun didn’t shine on threshing day. The world always seemed warm and yellow. A ‘meitheall’ of neighbours – as many as 10 – had gathered in the yard, and were chatting and watching as Tangney’s towering yellow thresher was manoeuvred into position alongside the ricks of barley that had mellowed and rested in the autumn sunshine for weeks.

The excitement had begun weeks earlier when the reaper ’n’ binder – an exciting sight in itself – had come to cut the barley. I followed it as it slowly cut a swathe through the crackling barley and methodically and regularly kicked out the bound sheaves with a heavy click. My father and a few helpers followed, stooking quietly as they went. The dog ran around excitedly as I dashed from stook to stook. The stubble stung my feet.

Tangneys of Castlemaine threshed from September right through until St. Patrick’s Day and sometimes beyond. They progressed westwards along the Castlemaine-Dingle road on the Dingle Penninsula through Boolteens, Keel, Inch and on as far as Dingle.

To my mind, it appeared to be a magical journey to wonderful places with a fascinating machine. They threshed some of the corn on the westward trip and the remainder on the homeward journey when the grain was well and truly ready. The great threshing odyssey was punctuated with sing-songs and harvest parties and none was as lively as when they reached Dingle.

The big belt was connected from the tractor to the thresher and it soon looped into action. A loud humming noise built up and filled the yard. Mick Enright and my father piked the sheaves from the rick onto the thresher. The twine was cut and the sheaf was fed into the drum. The grain sacks were filled and carried to the shed. The grain felt cool as it poured through my fingers into the sack. At the other end of the thresher, a couple of men heaped the straw onto a new rick.

The oats were always my favourite. Its straw, grain and chaff had a soft, smooth quality. The chaff from the barley used to stick to my clothes and tickle me. I was quickly covered with the stuff. I needed a rest and headed for the kitchen.

The table was laden with food of all sorts. There was white and brown bread, butter, thick slices of ham and brown sauce. Pots sizzled on the cooker. Mother and Mrs. Carroll headed out with mugs of tea and slices of thick currant bread. Bottles of stout were produced. My father wiped the sweat from his forehead and downed one. Chaff and dust danced in the beams of mellow light that shone through the big ash tree in the corner. There was a golden warm atmosphere in the yard.

My father cracked a match and lit a cigarette. “Mind where you throw that match, Paddy,” joked Mick Enright.

“We don’t want a conflagration”, added Pats Shea.

Suddenly my father started jumping up and down on the rick. At the same time Patrick Hickey fumbled in the barley for the fag that had fallen out of his grasp. He threw it into the ditch and stamped on the straw to stifle the flames. It had the makings of a wondrous duet as father then began to twitch and slap his trousers vigorously.

He had the stage and everyone’s attention as he shook, twisted and danced in the manner of an intoxicated Indian high on firewater or a crazed Morris dancer. He shouted something along the lines of “the divil take ya” and fell on his back on the barley. He then sat up. Strands of barley were stuck to his hair. He looked like an agricultural Stan Laurel. The silent bemusement of the onlookers had given way to curious laughter.

“What’s up, Paddy?”

“A bloody mouse ran up the leg of my trousers,” he replied as he looked around.

“And where is he?”

“Devil if I know,” he replied to a burst of laughter as he gave his trousers another slap.

“Here Paddy, put that on your head,” said Jim Cronin, handing him a bottle of stout.

“I think you’ll need something stronger than that,” advised Mick Enright as he headed into the back kitchen. He returned with a bottle of whiskey and a few mugs. He poured Paddy a drink. He swilled it in the mug and savoured a deep draught. He wiped his brow and took another swallow.

“God Paddy, you’d go to any length for a proper drink,” said Pats Shea.

“Well I don’t want to go through that again, the little shagger.”

“Kitty said you can never dance when she’s around.”

“Well here’s to the harvest, Paddy and the mouse!”

They clicked mugs and laughed.

Soon they were back at work. My father now had his trouser legs tied with two pieces of blue binder twine. There was half a rick of barley still to thresh. And when the last sheaf had been tossed and the dust had settled they sat in the shade of the new rick of straw, pulled the heads off a few bottles, passed around the cigarettes and rested. There was a contented silence for a while.

“I wonder is he any relation?” inquired Mick Enright.

“Who?” asked my father.

“The mouse,” he replied.

“What are you on about?”

“I wonder is that mouse any relation to the fellow who started the great Chicago fire?” inquired Mick.

“T’anam don diabhal, that wasn’t a mouse. ‘Twas a cow kicked over Mrs O’Leary’s lamp,” Dad informed him.

“I could have sworn it was a mouse. The memory plays strange tricks. Well it could have been just as serious. As Pats said we could have had a conflagration.”

“The divil take him.”

There was a contented chuckle.

The yard was suffused with a gentle, golden glow. The rick of straw had risen to touch the lowest branches and was having the finishing touches applied. The bags of barley were stacked high in the shed.

They chatted and joked for a while and then answered the call to head in for supper. Soon Tangneys and their enchanting machine departed, rattling the ash branches as they went. They left a void and a mound of chaff.

I felt a little sadness as the neighbours vanished into the evening, their names echoing in farewell. There was a strange silence in the yard – not even a rustle. Beyond the yellow rick, through the great ash tree, I could see the setting sun, large and golden, ripening Slieve Mish’s heather to a flaxen bloom.

Dan Daly is a native of Kerry but lives in Robinstown, Navan, Co Meath. A recently retired primary school principal, he is married with three children. He writes as a hobby.

SHARING OPTIONS