It’s now two years since quotas were removed and 2017 is shaping up to be the first half-decent milk price year since the quota shackles came off. Reasonably good weather, a good milk price and long summer days exude positivity among dairy farmers. But listening to farmers, there’s a big conflict between what different groups of farmers are saying.

On the one hand, a cohort of farmers are converting from beef and tillage to dairy farming. Others are expanding their existing dairy farms by taking on neighbouring land or setting up second or even third units.

But, on the other hand, another and much larger cohort of farmers are reeling from a busy spring and the thing at the front of their minds is the labour shortage. They are wondering how they will cope with another spring without extra help. Taking on extra cows or a second farm is far from their minds as they are struggling to find help to farm what they have without being burned out.

It’s hard to square this circle, or reconcile the fact that some farmers just see the opportunity and the return from dairy farming while others see the risks and the challenges, particularly around labour. Neither are wrong – every factor needs to be weighed up and analysed. Expansion is not and should not be for everyone.

So what are the options for those who want to expand, or need to expand in order to create a bigger income for their family?

Before ever looking over the ditch, the most effective way to maximise profit and ultimately return on capital is to get the home farm humming. The highest return from farming is to farm your existing land as best you can, optimising the number of cows being milked from the home farm.

This involves investing in soil fertility to grow more grass, getting replacement heifers contract reared and expanding the milking platform by leasing more land.

Next step

But the opportunity to rent land next door does not present itself to everyone. Some farmers who have achieved all they can on their existing farm, and have the motivation, capacity and drive, are looking at second units.

There is a risk that this option may become fashionable and turn into a vanity project for some farmers. The term ‘‘second unit’’ is being bandied about a lot more much in the same way as “second houses” became fashionable in the Celtic Tiger era. But farmers need to be clear about the risks involved. If a dog is not just for Christmas, then a second unit is not just for when milk prices are high or when the weather is dry.

Having said that, many successful farmers invested off farm during the Celtic Tiger in a bid to get their money working for them. And many got badly burned. At least now, with quotas gone, when a farmer invests in another farm he has control of his or her investment, can see where their money is going and, more importantly can see how and when it is going to come back.

It requires a whole new skillset to manage a second unit. You physically can’t do all of the work on both farms every day. Recruiting and managing people are skills that many farmers struggle with after expansion. Others flourish. It depends on skillset, experience and personality type. But managing people is a big challenge and it’s a risk of running multiple farms.

It can be overcome by operating simple systems, having clearly defined protocols and procedures in place and learning to communicate effectively. The managing people side of things does not just relate to employees.

It also relates to dealing with landowners, bank managers, contractors and family. It also relates to how the farmer reacts to the inevitable stress that will come his/her way when dealing with all these people who have different outlooks, goals and objectives than their own.

The other big challenge is to manage the actual business. In many cases, taking on a second unit may mean the business doubles in size overnight.

Depending on the structure used, debt levels may be many multiples of what they were so the farm commitments will be much greater than before. Keeping on top of this requires a significant increase in the time dedicated to managing the overall business, particularly cashflow.

If you dislike doing cashflow budgets and business plans or tend to leave office work on the long finger in favour of the physical work, then maybe running a second unit is not right for you.

Structure

There are a number of things to look for when evaluating a farming proposal. Looking at the return on capital from the investment is the first step. Calculating the return on capital (ROC) allows you to compare it against other proposals or different investments. Calculate the return on capital based on the projected net profit in year three, add back the interest and divide by the total capital cost of the investment, regardless of whether it is borrowed or not.

When looking at second units, the ROC will be greatest on rented farms. This is because the capital input into a rented farm is much less than when buying a farm, even where infrastructure and stock need to be purchased.

Aside from ROC, the amount of money earned from the investment is also important. A high ROC is all well and good, but it is the sum of money dropping out at the end of the year that is as important.

For example, one proposal might offer an ROC of 20%, but the projected annual cash surplus may only be €5,000. Another proposal might offer a lower ROC, eg 10% per year, but the cash surplus from this investment could be €50,000 per year. Of course, the lower ROC proposal had to involve a bigger investment on day one.

While the ROC will be higher from renting a farm, some farmers will still prefer to buy a farm. This option is out of reach for many as they don’t have sufficient equity (other owned land which can be used as security) or cash to put into the project. Repayment capacity is another big stumbling block for many farmers.

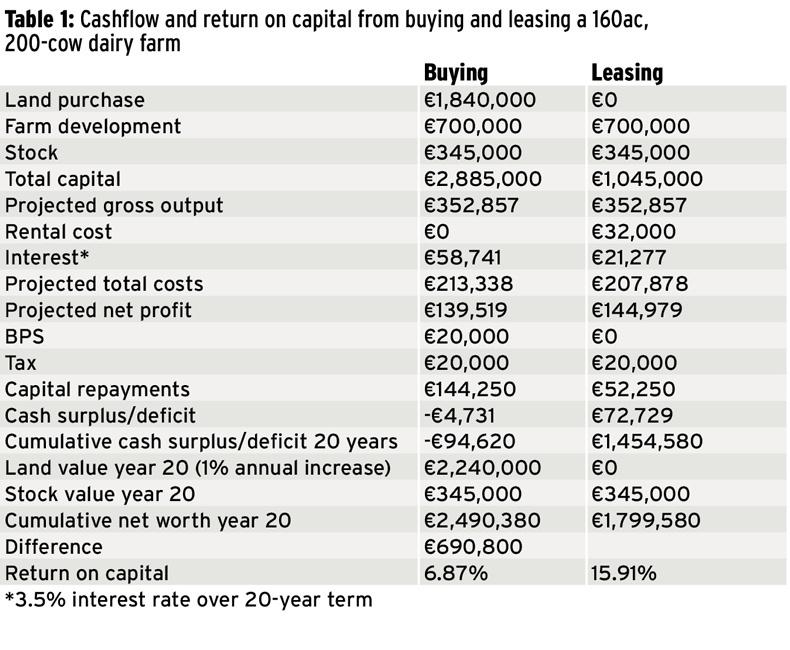

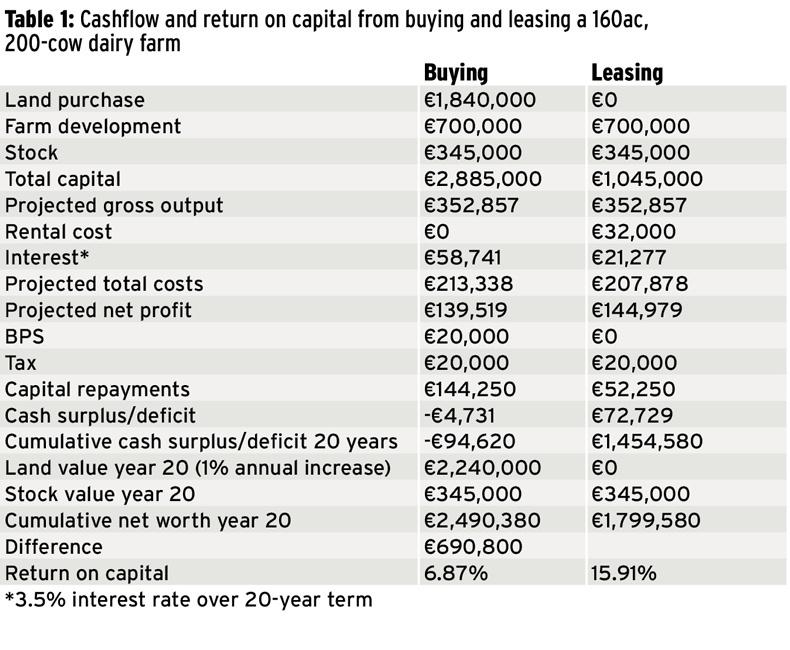

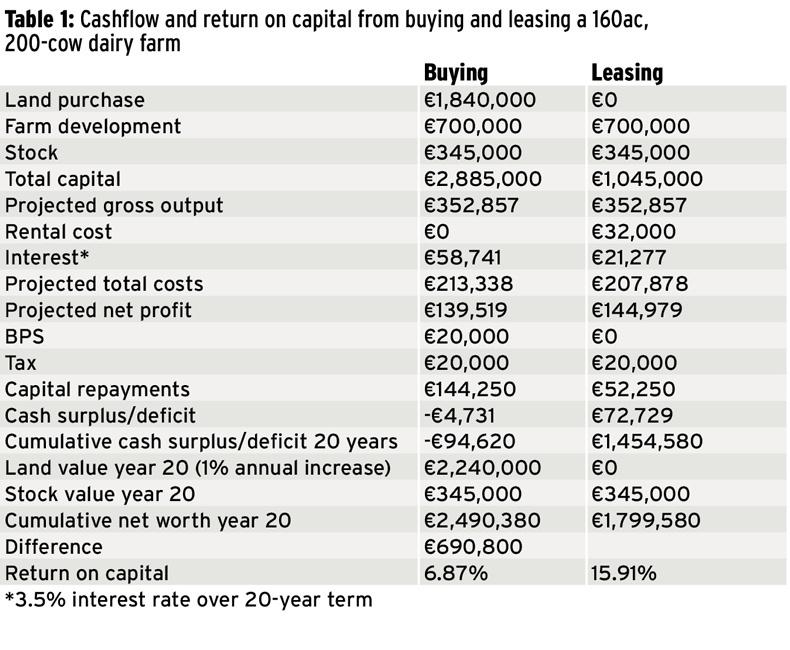

As detailed in Table 1, the total difference in net worth after 20 years between buying and leasing a 160ac and 200-cow farm are not as great as one might think. The big issue with buying is that the farm will be operating at a cash deficit for the duration of time that capital is being repaid, so this option is only sustainable when it is viewed in the context of an overall business. For example, the home farm might be throwing off sufficient cash every year to fund a cash deficit on a purchased farm.

In the example, buying the farm leaves a cash deficit of €4,731 per year while renting the farm leaves a cash surplus of €72,729 per year. But in year 20, when you include the value of the owned land, cumulative net worth is greater to the tune of €690,800 after buying the farm.

There are a number of big unknowns associated with the figures in Table 1. The first is the actual performance. It is presumed that these results are achieved on year three of the project using this year’s milk price. The next is the value of land in 20 years’ time. In this example, it is presumed that land values increase by 1% per year compounding. The other big unknown is what if the cash surplus from renting the farm was reinvested at a similar rate of return.

The last unknown is the future income potential of the land that is now debt free. This could be farmed for another 20 years debt free, or leased out tax-free.

Other things to consider are your own time and input into the proposal and the amount of collateral and equity tied up in the project. Taking on a second unit is taking on a risk, but there is no reward without risk. So the priority should be to mitigate risks. This is where cashflows and business plans come into play. Be conservative on output and prices and allow for leeway in unexpected costs. If the project is profitable at low prices, it will be even more profitable at high prices, provided costs don’t change. Be aware that the performance of the home farm may drop after taking on a second unit as your time input to the management of the farm will be more stretched.

Taxation is another consideration. If operating as a sole trader, the cash used to pay down debt is taxed at whatever tax band you are in, ie capital repayments are not a business expense. However, farmers that are operating in limited companies, and where the debt is attached to the company have a lot more cash available to pay down debt than sole traders.

Top tips for successful second units

1

Work with good people that you trust. Nearly all second units involve some degree of collaboration, whether it is with landowners or business partners. Do your due diligence and get the governance right. This means doing background checks on the people involved and working out and agreeing in advance what will happen in certain scenarios. The exit strategy should nearly be the first thing to be agreed.

2

Make sure that the proposal is sound. Do a realistic business plan, capital budget and cashflow forecast. Budget for lower milk prices and lower milk output than you hope for. Seek help and advice from people with prior experience on setting up second farms.

3

Keep the system simple. Simple systems are ones that require a limited number of decisions to be made each day for the farm to run effectively. Some farmers just have milking cows on the second unit with youngstock reared elsewhere. Some even calve all the cows on the home farm and transport them back to the second unit in batches after calving.

4

People who operate second units successfully are good at communicating. They explain what they want and then delegate responsibility to employees or contractors to carry out the work. You must have good people skills.

It’s now two years since quotas were removed and 2017 is shaping up to be the first half-decent milk price year since the quota shackles came off. Reasonably good weather, a good milk price and long summer days exude positivity among dairy farmers. But listening to farmers, there’s a big conflict between what different groups of farmers are saying.

On the one hand, a cohort of farmers are converting from beef and tillage to dairy farming. Others are expanding their existing dairy farms by taking on neighbouring land or setting up second or even third units.

But, on the other hand, another and much larger cohort of farmers are reeling from a busy spring and the thing at the front of their minds is the labour shortage. They are wondering how they will cope with another spring without extra help. Taking on extra cows or a second farm is far from their minds as they are struggling to find help to farm what they have without being burned out.

It’s hard to square this circle, or reconcile the fact that some farmers just see the opportunity and the return from dairy farming while others see the risks and the challenges, particularly around labour. Neither are wrong – every factor needs to be weighed up and analysed. Expansion is not and should not be for everyone.

So what are the options for those who want to expand, or need to expand in order to create a bigger income for their family?

Before ever looking over the ditch, the most effective way to maximise profit and ultimately return on capital is to get the home farm humming. The highest return from farming is to farm your existing land as best you can, optimising the number of cows being milked from the home farm.

This involves investing in soil fertility to grow more grass, getting replacement heifers contract reared and expanding the milking platform by leasing more land.

Next step

But the opportunity to rent land next door does not present itself to everyone. Some farmers who have achieved all they can on their existing farm, and have the motivation, capacity and drive, are looking at second units.

There is a risk that this option may become fashionable and turn into a vanity project for some farmers. The term ‘‘second unit’’ is being bandied about a lot more much in the same way as “second houses” became fashionable in the Celtic Tiger era. But farmers need to be clear about the risks involved. If a dog is not just for Christmas, then a second unit is not just for when milk prices are high or when the weather is dry.

Having said that, many successful farmers invested off farm during the Celtic Tiger in a bid to get their money working for them. And many got badly burned. At least now, with quotas gone, when a farmer invests in another farm he has control of his or her investment, can see where their money is going and, more importantly can see how and when it is going to come back.

It requires a whole new skillset to manage a second unit. You physically can’t do all of the work on both farms every day. Recruiting and managing people are skills that many farmers struggle with after expansion. Others flourish. It depends on skillset, experience and personality type. But managing people is a big challenge and it’s a risk of running multiple farms.

It can be overcome by operating simple systems, having clearly defined protocols and procedures in place and learning to communicate effectively. The managing people side of things does not just relate to employees.

It also relates to dealing with landowners, bank managers, contractors and family. It also relates to how the farmer reacts to the inevitable stress that will come his/her way when dealing with all these people who have different outlooks, goals and objectives than their own.

The other big challenge is to manage the actual business. In many cases, taking on a second unit may mean the business doubles in size overnight.

Depending on the structure used, debt levels may be many multiples of what they were so the farm commitments will be much greater than before. Keeping on top of this requires a significant increase in the time dedicated to managing the overall business, particularly cashflow.

If you dislike doing cashflow budgets and business plans or tend to leave office work on the long finger in favour of the physical work, then maybe running a second unit is not right for you.

Structure

There are a number of things to look for when evaluating a farming proposal. Looking at the return on capital from the investment is the first step. Calculating the return on capital (ROC) allows you to compare it against other proposals or different investments. Calculate the return on capital based on the projected net profit in year three, add back the interest and divide by the total capital cost of the investment, regardless of whether it is borrowed or not.

When looking at second units, the ROC will be greatest on rented farms. This is because the capital input into a rented farm is much less than when buying a farm, even where infrastructure and stock need to be purchased.

Aside from ROC, the amount of money earned from the investment is also important. A high ROC is all well and good, but it is the sum of money dropping out at the end of the year that is as important.

For example, one proposal might offer an ROC of 20%, but the projected annual cash surplus may only be €5,000. Another proposal might offer a lower ROC, eg 10% per year, but the cash surplus from this investment could be €50,000 per year. Of course, the lower ROC proposal had to involve a bigger investment on day one.

While the ROC will be higher from renting a farm, some farmers will still prefer to buy a farm. This option is out of reach for many as they don’t have sufficient equity (other owned land which can be used as security) or cash to put into the project. Repayment capacity is another big stumbling block for many farmers.

As detailed in Table 1, the total difference in net worth after 20 years between buying and leasing a 160ac and 200-cow farm are not as great as one might think. The big issue with buying is that the farm will be operating at a cash deficit for the duration of time that capital is being repaid, so this option is only sustainable when it is viewed in the context of an overall business. For example, the home farm might be throwing off sufficient cash every year to fund a cash deficit on a purchased farm.

In the example, buying the farm leaves a cash deficit of €4,731 per year while renting the farm leaves a cash surplus of €72,729 per year. But in year 20, when you include the value of the owned land, cumulative net worth is greater to the tune of €690,800 after buying the farm.

There are a number of big unknowns associated with the figures in Table 1. The first is the actual performance. It is presumed that these results are achieved on year three of the project using this year’s milk price. The next is the value of land in 20 years’ time. In this example, it is presumed that land values increase by 1% per year compounding. The other big unknown is what if the cash surplus from renting the farm was reinvested at a similar rate of return.

The last unknown is the future income potential of the land that is now debt free. This could be farmed for another 20 years debt free, or leased out tax-free.

Other things to consider are your own time and input into the proposal and the amount of collateral and equity tied up in the project. Taking on a second unit is taking on a risk, but there is no reward without risk. So the priority should be to mitigate risks. This is where cashflows and business plans come into play. Be conservative on output and prices and allow for leeway in unexpected costs. If the project is profitable at low prices, it will be even more profitable at high prices, provided costs don’t change. Be aware that the performance of the home farm may drop after taking on a second unit as your time input to the management of the farm will be more stretched.

Taxation is another consideration. If operating as a sole trader, the cash used to pay down debt is taxed at whatever tax band you are in, ie capital repayments are not a business expense. However, farmers that are operating in limited companies, and where the debt is attached to the company have a lot more cash available to pay down debt than sole traders.

Top tips for successful second units

1

Work with good people that you trust. Nearly all second units involve some degree of collaboration, whether it is with landowners or business partners. Do your due diligence and get the governance right. This means doing background checks on the people involved and working out and agreeing in advance what will happen in certain scenarios. The exit strategy should nearly be the first thing to be agreed.

2

Make sure that the proposal is sound. Do a realistic business plan, capital budget and cashflow forecast. Budget for lower milk prices and lower milk output than you hope for. Seek help and advice from people with prior experience on setting up second farms.

3

Keep the system simple. Simple systems are ones that require a limited number of decisions to be made each day for the farm to run effectively. Some farmers just have milking cows on the second unit with youngstock reared elsewhere. Some even calve all the cows on the home farm and transport them back to the second unit in batches after calving.

4

People who operate second units successfully are good at communicating. They explain what they want and then delegate responsibility to employees or contractors to carry out the work. You must have good people skills.

SHARING OPTIONS