Sharemilking on dairy farms in Ireland has got off to a slow and rocky start. There are only a handful of sharemilking arrangements in place.

Others started but have already failed. No doubt lessons have been learned from the experience on all sides and the expectation is that sharemilking as a viable career opportunity for young people will be a real option.

In a sharemilking agreement, a land owner and a herd owner come together to run two separate businesses from the one farm. The farm owner provides the land, housing and milking facilities, while the sharemilker provides the cows, labour and any machinery or equipment needed to run the farm.

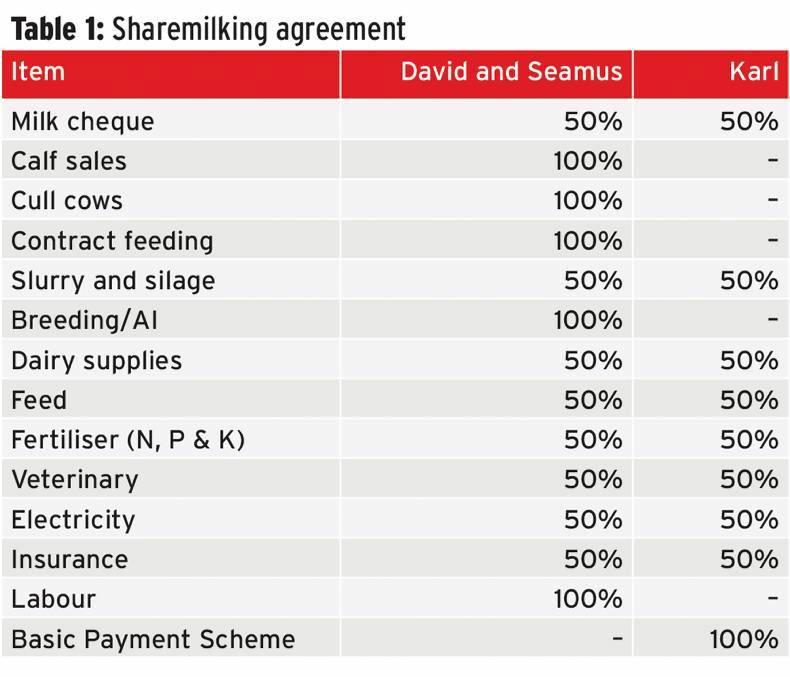

In most agreements, the milk cheque is divided equally between the two parties. Some costs, such as purchased feed, nitrogen fertiliser and vet bills, are split 50-50. Other costs, such as labour and the costs of feeding the animals over the winter (machinery or contractor), lie entirely with the sharemilker, while costs such as farm maintenance and staff housing are the responsibility of the farm owner.

Why?

For the farm owner, it allows them to take a step back from the day-to-day management of the farm. They benefit from having young, ambitious and hard-working people running their farm who have a vested interest in good performance.

Typically, land owners have less money tied up in the farm, as they no longer own the herd. Often this releases equity for farmers who were previously owner operators for retirement or other investments.

A sharemilking couple was featured in last week’s Irish Farmers Journal. For them, the benefits of sharemilking are huge. Firstly, they are doing what they love – dairy farming.

They are their own bosses, working for themselves, and have regular, structured meetings with the farm owner who is also their mentor. They don’t have the money to buy land (just yet), but sharemilking gives them the opportunity to invest in high-return areas such as cows.

Finally, they are increasing their wealth as they pay down debt on their stock loan with the ultimate ambition to be farm owners in the next 10 years.

The evidence from New Zealand says that sharemilking farms are more profitable than owner-operated farms or farms where managers are employed.

Most sharemilking arrangements last for a period of three years, after which the agreement might be renewed, or a successful sharemilker moves on to a larger farm or takes the next step and buys a farm.

Obstacles

Up to recently, the biggest obstacle in the way of sharemilking in Ireland was scale at farm level and milk quota regulations limiting growth potential of dairy businesses.

With supply constraints now removed, other obstacles have emerged. The issues around sourcing suitable farms, the attitudes of existing farm owners and the tax implications of sharemilking have surfaced. However, by and large, these are not the biggest stumbling blocks towards successful sharemilking.

We were completely naïve in thinking that milk quotas, or a lack of suitable farms or farmers willing to work with young people was holding back sharemilking

The biggest obstacle is actually a lack of young people capable of taking on herd ownership. Paidi Kelly from Teagasc Moorepark is one of a number of people working behind the scenes to make sharemilking happen:

“We were completely naïve in thinking that milk quotas, or a lack of suitable farms or farmers willing to work with young people was holding back sharemilking,” he said.

“When we think about it, a career in farming is like climbing a ladder and sharemilking is three or four steps up that ladder, but the problem at the moment is that some of the bottom steps are missing, so the pool of people with all of the skills necessary to go sharemilking is small.”

Skills

So what skills are required? Obviously, being able to manage cows and grass is very important. But generally these skills are not what young people are lacking, especially those who have gone through a couple of years of hands-on agricultural training and have experience of managing dairy farms.

Two critical skills which many young people are lacking and which are holding them back from taking the next step in their career are business and people skills.

In terms of business skills, what is needed here is the ability to assess an opportunity, the ability to read and understand a budget and cashflow forecast, but, more importantly, to have a track record of saving with a bank. This is important when looking for a loan to buy stock.

People skills are really important and are developed from 15 to 25 years of age. It involves the ability to communicate effectively with someone, to read a situation and to see things from someone else’s perspective.

These skills are needed for sharemilkers when managing staff, but also when dealing with and building up the trust of farm owners, banks and others who invest time and money into the sharemilker.

Successful sharemilkers have a positive influence on the people around them, backed up by ample ability at the basics of managing grass and cows.

People and business skills cannot all be taught in the classroom. There is an onus on existing farmers to develop sharemilkers of the future, by teaching these business and people skills to their children and to young people working on their farms through example and exposure. As the New Zealanders say of their farming neighbours, “they are training my future sharemilkers and I am training theirs”.

According to Paidi, there is a potential win-win for the current generation of farmers too, as bringing young people along in a mentoring capacity can open up opportunities for existing farm businesses to grow and expand.

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

“When I crunched the numbers, dairy farming was going to offer the highest rate of return. I want to be involved in the business, but not to be hands-on,” he said.

“My area of expertise is not in managing cows or grass, but I do own the land and I want to have a say in how the farm operates.”

Karl converted the farm to dairy towards the end of 2014, investing in milking facilities including a 16-unit DeLaval milking parlour (photo below), reseeding, roadways, fencing and water, while new outdoor cubicles are being built this year. In total, close to €500,000 was spent converting the farm to set it up as a 200-cow unit for spring 2015.

The next job was to find a sharemilker. He got on to Austin Finn in the

Effectively, there are four people involved. As the herd owners, David and Seamus have ultimate responsibility for how the farm performs and Brian is their employee. As the land owner, Karl places trust in David and Seamus to do a good job.

Communication between all four men is crucial. They have a WhatsApp group set up on their phones. Photos are taken of all milk statements, collection test results, invoices and dockets and are sent to everyone at the same time.

In fact, administration and getting suppliers to split invoices has been the biggest challenge on the farm to date.

David and Seamus meet Karl regularly to review performance, budgets and to discuss issues on the farm.

The current agreement lasts for three years.

Comment

The opportunities for sharemilking are there. There are more opportunities for farms than there are people to farm them, as Karl experienced when he went looking for a sharemilker.

For me, sharemilking provides the ideal win-win between a farm owner looking to take a step back from farming or, like in Karl’s case, has a land block that he wants to make more use out of and a young person keen to go dairy farming.

Sharemilking should also be considered as a form of succession planning when transferring the family farm to the next generation, whereby a son or daughter sharemilks on a home farm with the parents taking a back seat before fully transferring the farm.

Access to finance for the young person starting off is rarely as big an obstacle as one might think. The reality is that if all the skills are present – grass, cows, people and business – then capital will never be lacking. A much bigger issue is the incentive for land owners to let out their land in a long-term tax-free lease. Government and farm organisations take note that a similar incentive is needed to encourage land owners to enter into a sharemilking arrangement.

The long-term rural economic advantages of sharemilking are much greater than leasing, which is always skewed in the favour of larger, established farmers with the money available to secure a lease. It’s time we got serious about creating viable and attainable opportunities for young people interested in farming as a career. Not everyone is sharemilker standard, but those who are should get the opportunity.

Read more

Full coverage: sharemilking

Sharemilking on dairy farms in Ireland has got off to a slow and rocky start. There are only a handful of sharemilking arrangements in place.

Others started but have already failed. No doubt lessons have been learned from the experience on all sides and the expectation is that sharemilking as a viable career opportunity for young people will be a real option.

In a sharemilking agreement, a land owner and a herd owner come together to run two separate businesses from the one farm. The farm owner provides the land, housing and milking facilities, while the sharemilker provides the cows, labour and any machinery or equipment needed to run the farm.

In most agreements, the milk cheque is divided equally between the two parties. Some costs, such as purchased feed, nitrogen fertiliser and vet bills, are split 50-50. Other costs, such as labour and the costs of feeding the animals over the winter (machinery or contractor), lie entirely with the sharemilker, while costs such as farm maintenance and staff housing are the responsibility of the farm owner.

Why?

For the farm owner, it allows them to take a step back from the day-to-day management of the farm. They benefit from having young, ambitious and hard-working people running their farm who have a vested interest in good performance.

Typically, land owners have less money tied up in the farm, as they no longer own the herd. Often this releases equity for farmers who were previously owner operators for retirement or other investments.

A sharemilking couple was featured in last week’s Irish Farmers Journal. For them, the benefits of sharemilking are huge. Firstly, they are doing what they love – dairy farming.

They are their own bosses, working for themselves, and have regular, structured meetings with the farm owner who is also their mentor. They don’t have the money to buy land (just yet), but sharemilking gives them the opportunity to invest in high-return areas such as cows.

Finally, they are increasing their wealth as they pay down debt on their stock loan with the ultimate ambition to be farm owners in the next 10 years.

The evidence from New Zealand says that sharemilking farms are more profitable than owner-operated farms or farms where managers are employed.

Most sharemilking arrangements last for a period of three years, after which the agreement might be renewed, or a successful sharemilker moves on to a larger farm or takes the next step and buys a farm.

Obstacles

Up to recently, the biggest obstacle in the way of sharemilking in Ireland was scale at farm level and milk quota regulations limiting growth potential of dairy businesses.

With supply constraints now removed, other obstacles have emerged. The issues around sourcing suitable farms, the attitudes of existing farm owners and the tax implications of sharemilking have surfaced. However, by and large, these are not the biggest stumbling blocks towards successful sharemilking.

We were completely naïve in thinking that milk quotas, or a lack of suitable farms or farmers willing to work with young people was holding back sharemilking

The biggest obstacle is actually a lack of young people capable of taking on herd ownership. Paidi Kelly from Teagasc Moorepark is one of a number of people working behind the scenes to make sharemilking happen:

“We were completely naïve in thinking that milk quotas, or a lack of suitable farms or farmers willing to work with young people was holding back sharemilking,” he said.

“When we think about it, a career in farming is like climbing a ladder and sharemilking is three or four steps up that ladder, but the problem at the moment is that some of the bottom steps are missing, so the pool of people with all of the skills necessary to go sharemilking is small.”

Skills

So what skills are required? Obviously, being able to manage cows and grass is very important. But generally these skills are not what young people are lacking, especially those who have gone through a couple of years of hands-on agricultural training and have experience of managing dairy farms.

Two critical skills which many young people are lacking and which are holding them back from taking the next step in their career are business and people skills.

In terms of business skills, what is needed here is the ability to assess an opportunity, the ability to read and understand a budget and cashflow forecast, but, more importantly, to have a track record of saving with a bank. This is important when looking for a loan to buy stock.

People skills are really important and are developed from 15 to 25 years of age. It involves the ability to communicate effectively with someone, to read a situation and to see things from someone else’s perspective.

These skills are needed for sharemilkers when managing staff, but also when dealing with and building up the trust of farm owners, banks and others who invest time and money into the sharemilker.

Successful sharemilkers have a positive influence on the people around them, backed up by ample ability at the basics of managing grass and cows.

People and business skills cannot all be taught in the classroom. There is an onus on existing farmers to develop sharemilkers of the future, by teaching these business and people skills to their children and to young people working on their farms through example and exposure. As the New Zealanders say of their farming neighbours, “they are training my future sharemilkers and I am training theirs”.

According to Paidi, there is a potential win-win for the current generation of farmers too, as bringing young people along in a mentoring capacity can open up opportunities for existing farm businesses to grow and expand.

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

“When I crunched the numbers, dairy farming was going to offer the highest rate of return. I want to be involved in the business, but not to be hands-on,” he said.

“My area of expertise is not in managing cows or grass, but I do own the land and I want to have a say in how the farm operates.”

Karl converted the farm to dairy towards the end of 2014, investing in milking facilities including a 16-unit DeLaval milking parlour (photo below), reseeding, roadways, fencing and water, while new outdoor cubicles are being built this year. In total, close to €500,000 was spent converting the farm to set it up as a 200-cow unit for spring 2015.

The next job was to find a sharemilker. He got on to Austin Finn in the

Effectively, there are four people involved. As the herd owners, David and Seamus have ultimate responsibility for how the farm performs and Brian is their employee. As the land owner, Karl places trust in David and Seamus to do a good job.

Communication between all four men is crucial. They have a WhatsApp group set up on their phones. Photos are taken of all milk statements, collection test results, invoices and dockets and are sent to everyone at the same time.

In fact, administration and getting suppliers to split invoices has been the biggest challenge on the farm to date.

David and Seamus meet Karl regularly to review performance, budgets and to discuss issues on the farm.

The current agreement lasts for three years.

Comment

The opportunities for sharemilking are there. There are more opportunities for farms than there are people to farm them, as Karl experienced when he went looking for a sharemilker.

For me, sharemilking provides the ideal win-win between a farm owner looking to take a step back from farming or, like in Karl’s case, has a land block that he wants to make more use out of and a young person keen to go dairy farming.

Sharemilking should also be considered as a form of succession planning when transferring the family farm to the next generation, whereby a son or daughter sharemilks on a home farm with the parents taking a back seat before fully transferring the farm.

Access to finance for the young person starting off is rarely as big an obstacle as one might think. The reality is that if all the skills are present – grass, cows, people and business – then capital will never be lacking. A much bigger issue is the incentive for land owners to let out their land in a long-term tax-free lease. Government and farm organisations take note that a similar incentive is needed to encourage land owners to enter into a sharemilking arrangement.

The long-term rural economic advantages of sharemilking are much greater than leasing, which is always skewed in the favour of larger, established farmers with the money available to secure a lease. It’s time we got serious about creating viable and attainable opportunities for young people interested in farming as a career. Not everyone is sharemilker standard, but those who are should get the opportunity.

Read more

Full coverage: sharemilking

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

Karl Monaghan (photo, right) has a full-time job in Dublin. For the past 15 years, his 66ha farm in Clonfert, Co Galway, has been rented out to tillage farmers, but Karl has always wanted to get more out of the farm.

SHARING OPTIONS