Ireland today has one of the most integrated state-sponsored agricultural knowledge and innovation systems in Europe.

Teagasc is a one-stop agency that provides combined advisory, education and research services for Irish farmers.

It was established in 1988; however, this was over 40 years after it was originally recommended to the Government. Civil war politics were responsible for the hiatus.

When the Irish State was established 100 years ago, it was immediately divided by the Anglo-Irish Treaty that established it.

The beet factory in Carlow in operation.

By summer 1922, pro- and anti-Treatyites were embroiled in a civil war and although their conflict was quick, ending the following summer, the enmity unloosed ossified around pro-treaty Cumann na nGaedheal/Fine Gael and anti-treaty Fianna Fáil, and thereafter an internationally unique form of adversarial party politics persisted until the two parties entered coalition last year.

Given the importance of agriculture to the Irish economy and to Irish society more widely, it is not surprising that Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil’s rivalry was played out in the different agricultural policies that each pursued over the past century.

For instance, Fianna Fáil’s 1930s opposition to the dynamics of the livestock-export trade, which it pursued through the Economic War, and Fine Gael’s contrasting support for it is well known.

What is probably less recognised now is how the partisanship of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael affected the State’s promotion of agriculture.

It was the Marshall planners, based in Dublin after the second world war, who were charged with disbursing the American funding that was intended to resuscitate Europe’s shattered economies, who recommended what became Teagasc.

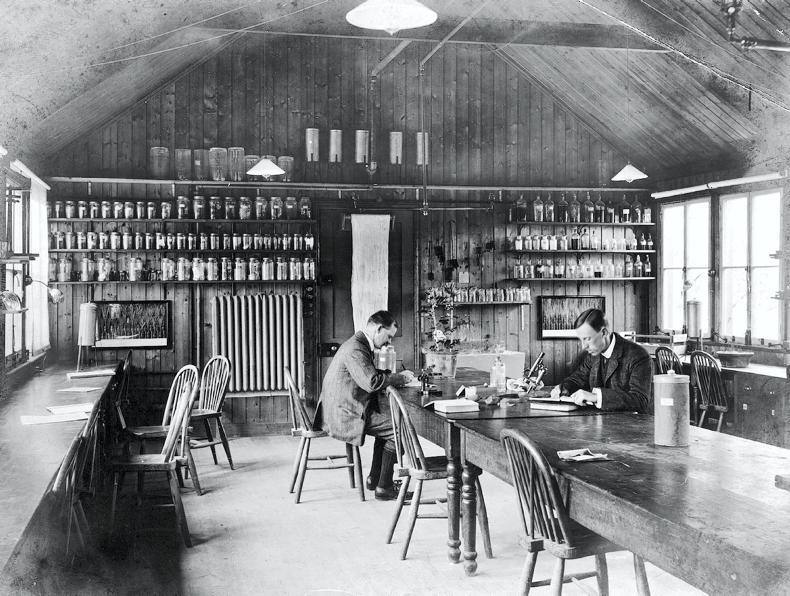

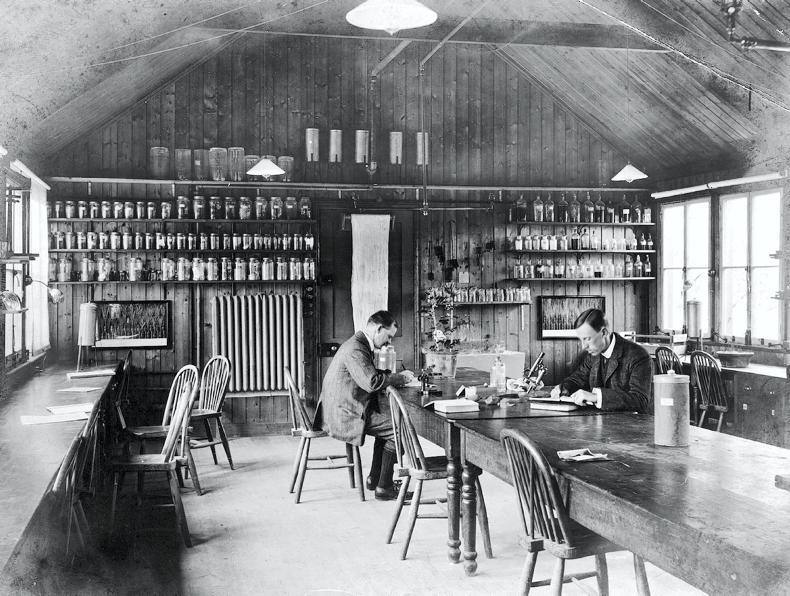

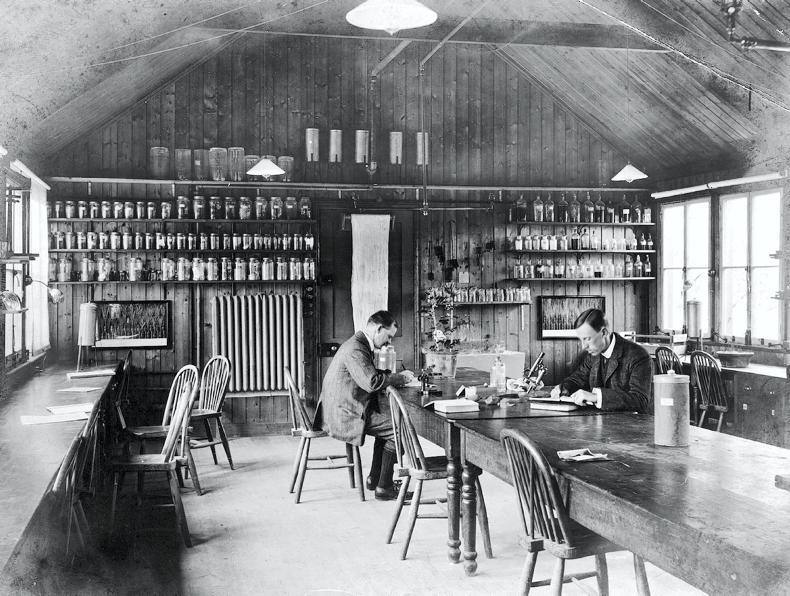

An agricultural science laboratory at the Albert Agricultural College in Dublin. \ Bernard Kaye

The Marshall Plan office in Dublin was headed up first by Irish-American Joseph E. Carrigan.

He wanted Irish agricultural productivity to increase exponentially, providing a breadbasket to support post-war industrial growth in Europe, and he knew, as the organiser of the successful agricultural extension programme in the state of Vermont, that what had helped US farmers to maximise outputs were combined advisory, education and research services.

At that point, Ireland largely had integrated advisory and education services, provided largely through the county committees of agriculture, but it had no research service at all.

Even establishing a research service proved fraught as the alternating Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael-led governments of the era vied to impose their own agendas.

As an east-coast American, a Philadelphian, Carrigan would have been personally unfamiliar with the rodeo sports of the western US, but in the arena of Irish politics he would have seen as much wrangling over his proposals for Irish agricultural services as at any bull ride.

A plaque at Teagasc Oak Park recognising US sponsorship of An Foras Talúntais. \ Eilish Cray and Teagasc

The establishment of An Foras Talúntais (AFT), the Agricultural Research Institute, was delayed until 1958. For a long time afterwards, there was little political appetite for a full integration and only in the 1970s did it return to political prominence.

By then there was much understandable reluctance to merge AFT, as it had matured into a standalone institution. Fianna Fáil took up the cause for its preservation and Fine Gael for full integration, and there followed another decade of inaction.

In 1980, the county committees of agriculture were amalgamated into a nationally administered advisory and education service, ACOT: An Chomhairle Oiliúna Talmhaíochta, but full integration was mothballed.

When it did happen in 1988 it was in the context of the contemporary cost-cutting exigency of the parlous 1980s, rather than newfound party-political consensus on the value of combined advisory, education and research services for Irish farmers. The Civil War of 1922–1923 already has a lot for which to answer in the court of Irish opinion, and to this can be added the inordinate delay in the delivery of what is now Teagasc.

Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh is a member of the Social Sciences Research Centre at the National University of Ireland, Galway and the history lecturer at Dublin Business School, and this article is based on his recent publication Developing Rural Ireland: a history of the Irish Agricultural Advisory Services (Wordwell Books, 2021).

Unsolicited advice is interference

When the agricultural advisory service began to operate in the early 1900s many farmers immediately started to interact with advisers, or instructors as they were then called.

These were, conspicuously, progressive farmers, and they or their families could often be categorised as agricultural improvers, who may have worked with the predecessors of the public advisers, such as the ‘gentlemen’ agriculturalists that the RDS had commissioned over the previous two centuries, or the first State-sponsored advisers, who had been sent into the west by the Congested Districts Board from 1891.

They also tended to be bigger farmers, who were formally educated and who were, disproportionately Protestant, with Catholic farmers remaining, understandably, wary of British state agents – which is what the public advisers were before Irish independence in 1922.

In the early years of the advisory service, though, most farmers would not have interacted with advisers, for many reasons.

For several decades, the ratio of farmers to advisers was very high. This was because, in the first instance, properly trained advisers were small in number, with the Royal College of Science in Dublin struggling to attract suitable candidates for its internationally pioneering course.

Then, subsequently, the resources of the impecunious new Irish State were insufficient to employ adequate numbers of advisers in every county.

In addition, a lot of farmers reacted against the top-down approach of the early advisers, who, unlike today’s advisers, did not engage in peer-to-peer dialogue with farmers but, instead, lectured to them.

By way of some contrast, farmers’ sons were more receptive to the advisory service, attending in large numbers, for example, the winter classes that the advisers ran as part of their outreach programme from the outset.

Interestingly, the farming sons were almost proxies for their fathers, who were curious about what the advisers had to say but were just not convinced of the value of it.

Equally, farmers’ wives and daughters were more receptive to the advisory service, as they fell into a quick and easy rapport with the poultry-keeping and butter-making instructresses, who were their female counterparts.

This latter relationship was crucial to the growth in the Irish poultry industry, especially and prodigiously, in the period leading up to the first world war (1914–18).

Gradually, as advisers moderated their approach and both they and adult male farmers, moreover, became increasingly comfortable with each other, a mutual esteem would develop that would encourage greater interaction and would lay the foundation for the dynamic in adviser-farmer exchange and knowledge transfer today.

Timeline of State intervention for rural Ireland in the

20th Century

1900 – Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction opened at 1–5 Merrion Street Upper, Dublin.

1900 – Royal College of Science, then on St Stephen’s Green, took in its first trainee agricultural instructors.

1900 – Albert Agricultural College, Glasnevin, began training horticultural and beekeeping instructors.

1900 – County-administered nationwide and specialised agricultural advisory service inaugurated. Each county would have its own advisory team, consisting of agricultural; horticultural and beekeeping; and poultry-keeping and butter-making instructors.

1904 – First rural domestic economy school for girls established at Portumna.

1904 – First agricultural school for boys established at Mountbellew.

1905 – Munster Institute, Cork, started to train poultry-keeping and butter-making instructresses.

1922 – Patrick Hogan became first Irish minister for agriculture.

1922 – Commission on Agriculture convened.

1923 – Hogan’s land act completed land transfer from landlords.

1927 – Dairy Disposal Company and Agricultural Credit Corporation created.

1933 – Fianna Fáil government founded Comhlucht Siúicre Éireann.

1934 – Project bringing Irish-speaking farmers from west to Meath began.

1940 – Wexford strawberry industry started.

1945 – National Soil Survey programme established at Johnstown Castle.

1949 – Minister for Agriculture James Dillon launched Land Rehabilitation Project.

1955 – Dillon launched Parish Plan.

1958 – Economic Development, White Paper by Department of Finance secretary TK Whitaker produced, with 11 of 24 chapters devoted to agriculture.

1958 – An Foras Talúntais (AFT) created.

1958 – Moorepark research centre established.

1959 – Winter farm schools introduced.

1959 – Farm Management Survey inaugurated.

1959 – Grange research centre founded.

1961 – Bord Bainne established, Kerrygold launched soon after.

1962 – Role of farm home management adviser created to supersede role of poultry-keeping and butter-making instructress.

1963 – Taoiseach Seán Lemass recommissioned Inter-Departmental Committee on the Problems of Small Western Farms.

1963 – Nítrigin Éireann Teoranta established to supply farmers with fertilisers.

1964 – Agriculture in the Second Programme for Economic Expansion published to guide policymaking in Lemass’s new economic dispensation.

1964 – ‘Pilot areas’ for agricultural development in west established.

1964 – Oak Park research centre opened.

1965 – Telefís Feirme, hosted by Justin Keating, began broadcasting on RTÉ.

1971 – Agriculture in the west of Ireland, or Scully report, published.

1972 – National Farm Survey established.

1973 – Ireland entered European Economic Community and started to participate in Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

1974 – Farm Modernisation Scheme began.

1975 – Disadvantaged Areas Scheme, leading to Western Drainage Scheme, began.

1977 – Prudent price policy introduced.

1970s – ‘Dairymis’, dairy herd management system, created.

1980 – County-administered advisory service amalgamated into nationally administered service, An Chomhairle Oiliúna Talmhaíochta (ACOT).

1981 – Western Package for rural development in west brought forward.

1982 – ‘Green Cert’ introduced.

1984 – Milk quotas introduced.

1984 – Farm home management advisers started to be retrained as socio-economic advisers.

1985 – Farm Improvement Programme began.

1987 – Bord Glas established.

1988 – ACOT and AFT integrated into amalgamated advisory, educational and research institute, Teagasc.

1988 – Coillte created.

1988 – LEADER began.

1989 – Operational Programme for Rural Development and Programme for Integrated Rural Development initiated.

1989 – Control of Farmyard Pollution scheme started.

1980s – Farm training centres constructed.

1992 – ‘MacSharry Reforms’ of CAP.

1992 – Small Farm Development Programme inaugurated.

1993 – Moorepark Technology Ltd opened.

1994 – Rural Environment Protection Scheme (REPS) launched.

1994 – Bord Bia created.

1994 – Scheme of Investment Aid for the Upgrading of On-Farm Dairying Facilities initiated.

1996 – ‘Cash-in-on-Grass’, ‘Responding to BSE’ and ‘Protein 3.50’ launched.

1997 – ‘Sheep 2-3-4’ unveiled.

1999 – Agenda 2000 amendments to CAP.

Ireland today has one of the most integrated state-sponsored agricultural knowledge and innovation systems in Europe.

Teagasc is a one-stop agency that provides combined advisory, education and research services for Irish farmers.

It was established in 1988; however, this was over 40 years after it was originally recommended to the Government. Civil war politics were responsible for the hiatus.

When the Irish State was established 100 years ago, it was immediately divided by the Anglo-Irish Treaty that established it.

The beet factory in Carlow in operation.

By summer 1922, pro- and anti-Treatyites were embroiled in a civil war and although their conflict was quick, ending the following summer, the enmity unloosed ossified around pro-treaty Cumann na nGaedheal/Fine Gael and anti-treaty Fianna Fáil, and thereafter an internationally unique form of adversarial party politics persisted until the two parties entered coalition last year.

Given the importance of agriculture to the Irish economy and to Irish society more widely, it is not surprising that Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil’s rivalry was played out in the different agricultural policies that each pursued over the past century.

For instance, Fianna Fáil’s 1930s opposition to the dynamics of the livestock-export trade, which it pursued through the Economic War, and Fine Gael’s contrasting support for it is well known.

What is probably less recognised now is how the partisanship of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael affected the State’s promotion of agriculture.

It was the Marshall planners, based in Dublin after the second world war, who were charged with disbursing the American funding that was intended to resuscitate Europe’s shattered economies, who recommended what became Teagasc.

An agricultural science laboratory at the Albert Agricultural College in Dublin. \ Bernard Kaye

The Marshall Plan office in Dublin was headed up first by Irish-American Joseph E. Carrigan.

He wanted Irish agricultural productivity to increase exponentially, providing a breadbasket to support post-war industrial growth in Europe, and he knew, as the organiser of the successful agricultural extension programme in the state of Vermont, that what had helped US farmers to maximise outputs were combined advisory, education and research services.

At that point, Ireland largely had integrated advisory and education services, provided largely through the county committees of agriculture, but it had no research service at all.

Even establishing a research service proved fraught as the alternating Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael-led governments of the era vied to impose their own agendas.

As an east-coast American, a Philadelphian, Carrigan would have been personally unfamiliar with the rodeo sports of the western US, but in the arena of Irish politics he would have seen as much wrangling over his proposals for Irish agricultural services as at any bull ride.

A plaque at Teagasc Oak Park recognising US sponsorship of An Foras Talúntais. \ Eilish Cray and Teagasc

The establishment of An Foras Talúntais (AFT), the Agricultural Research Institute, was delayed until 1958. For a long time afterwards, there was little political appetite for a full integration and only in the 1970s did it return to political prominence.

By then there was much understandable reluctance to merge AFT, as it had matured into a standalone institution. Fianna Fáil took up the cause for its preservation and Fine Gael for full integration, and there followed another decade of inaction.

In 1980, the county committees of agriculture were amalgamated into a nationally administered advisory and education service, ACOT: An Chomhairle Oiliúna Talmhaíochta, but full integration was mothballed.

When it did happen in 1988 it was in the context of the contemporary cost-cutting exigency of the parlous 1980s, rather than newfound party-political consensus on the value of combined advisory, education and research services for Irish farmers. The Civil War of 1922–1923 already has a lot for which to answer in the court of Irish opinion, and to this can be added the inordinate delay in the delivery of what is now Teagasc.

Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh is a member of the Social Sciences Research Centre at the National University of Ireland, Galway and the history lecturer at Dublin Business School, and this article is based on his recent publication Developing Rural Ireland: a history of the Irish Agricultural Advisory Services (Wordwell Books, 2021).

Unsolicited advice is interference

When the agricultural advisory service began to operate in the early 1900s many farmers immediately started to interact with advisers, or instructors as they were then called.

These were, conspicuously, progressive farmers, and they or their families could often be categorised as agricultural improvers, who may have worked with the predecessors of the public advisers, such as the ‘gentlemen’ agriculturalists that the RDS had commissioned over the previous two centuries, or the first State-sponsored advisers, who had been sent into the west by the Congested Districts Board from 1891.

They also tended to be bigger farmers, who were formally educated and who were, disproportionately Protestant, with Catholic farmers remaining, understandably, wary of British state agents – which is what the public advisers were before Irish independence in 1922.

In the early years of the advisory service, though, most farmers would not have interacted with advisers, for many reasons.

For several decades, the ratio of farmers to advisers was very high. This was because, in the first instance, properly trained advisers were small in number, with the Royal College of Science in Dublin struggling to attract suitable candidates for its internationally pioneering course.

Then, subsequently, the resources of the impecunious new Irish State were insufficient to employ adequate numbers of advisers in every county.

In addition, a lot of farmers reacted against the top-down approach of the early advisers, who, unlike today’s advisers, did not engage in peer-to-peer dialogue with farmers but, instead, lectured to them.

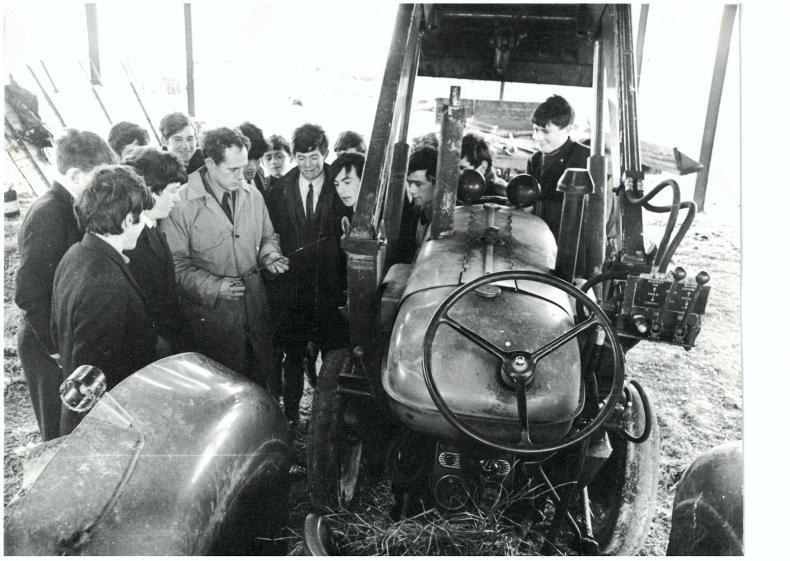

By way of some contrast, farmers’ sons were more receptive to the advisory service, attending in large numbers, for example, the winter classes that the advisers ran as part of their outreach programme from the outset.

Interestingly, the farming sons were almost proxies for their fathers, who were curious about what the advisers had to say but were just not convinced of the value of it.

Equally, farmers’ wives and daughters were more receptive to the advisory service, as they fell into a quick and easy rapport with the poultry-keeping and butter-making instructresses, who were their female counterparts.

This latter relationship was crucial to the growth in the Irish poultry industry, especially and prodigiously, in the period leading up to the first world war (1914–18).

Gradually, as advisers moderated their approach and both they and adult male farmers, moreover, became increasingly comfortable with each other, a mutual esteem would develop that would encourage greater interaction and would lay the foundation for the dynamic in adviser-farmer exchange and knowledge transfer today.

Timeline of State intervention for rural Ireland in the

20th Century

1900 – Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction opened at 1–5 Merrion Street Upper, Dublin.

1900 – Royal College of Science, then on St Stephen’s Green, took in its first trainee agricultural instructors.

1900 – Albert Agricultural College, Glasnevin, began training horticultural and beekeeping instructors.

1900 – County-administered nationwide and specialised agricultural advisory service inaugurated. Each county would have its own advisory team, consisting of agricultural; horticultural and beekeeping; and poultry-keeping and butter-making instructors.

1904 – First rural domestic economy school for girls established at Portumna.

1904 – First agricultural school for boys established at Mountbellew.

1905 – Munster Institute, Cork, started to train poultry-keeping and butter-making instructresses.

1922 – Patrick Hogan became first Irish minister for agriculture.

1922 – Commission on Agriculture convened.

1923 – Hogan’s land act completed land transfer from landlords.

1927 – Dairy Disposal Company and Agricultural Credit Corporation created.

1933 – Fianna Fáil government founded Comhlucht Siúicre Éireann.

1934 – Project bringing Irish-speaking farmers from west to Meath began.

1940 – Wexford strawberry industry started.

1945 – National Soil Survey programme established at Johnstown Castle.

1949 – Minister for Agriculture James Dillon launched Land Rehabilitation Project.

1955 – Dillon launched Parish Plan.

1958 – Economic Development, White Paper by Department of Finance secretary TK Whitaker produced, with 11 of 24 chapters devoted to agriculture.

1958 – An Foras Talúntais (AFT) created.

1958 – Moorepark research centre established.

1959 – Winter farm schools introduced.

1959 – Farm Management Survey inaugurated.

1959 – Grange research centre founded.

1961 – Bord Bainne established, Kerrygold launched soon after.

1962 – Role of farm home management adviser created to supersede role of poultry-keeping and butter-making instructress.

1963 – Taoiseach Seán Lemass recommissioned Inter-Departmental Committee on the Problems of Small Western Farms.

1963 – Nítrigin Éireann Teoranta established to supply farmers with fertilisers.

1964 – Agriculture in the Second Programme for Economic Expansion published to guide policymaking in Lemass’s new economic dispensation.

1964 – ‘Pilot areas’ for agricultural development in west established.

1964 – Oak Park research centre opened.

1965 – Telefís Feirme, hosted by Justin Keating, began broadcasting on RTÉ.

1971 – Agriculture in the west of Ireland, or Scully report, published.

1972 – National Farm Survey established.

1973 – Ireland entered European Economic Community and started to participate in Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

1974 – Farm Modernisation Scheme began.

1975 – Disadvantaged Areas Scheme, leading to Western Drainage Scheme, began.

1977 – Prudent price policy introduced.

1970s – ‘Dairymis’, dairy herd management system, created.

1980 – County-administered advisory service amalgamated into nationally administered service, An Chomhairle Oiliúna Talmhaíochta (ACOT).

1981 – Western Package for rural development in west brought forward.

1982 – ‘Green Cert’ introduced.

1984 – Milk quotas introduced.

1984 – Farm home management advisers started to be retrained as socio-economic advisers.

1985 – Farm Improvement Programme began.

1987 – Bord Glas established.

1988 – ACOT and AFT integrated into amalgamated advisory, educational and research institute, Teagasc.

1988 – Coillte created.

1988 – LEADER began.

1989 – Operational Programme for Rural Development and Programme for Integrated Rural Development initiated.

1989 – Control of Farmyard Pollution scheme started.

1980s – Farm training centres constructed.

1992 – ‘MacSharry Reforms’ of CAP.

1992 – Small Farm Development Programme inaugurated.

1993 – Moorepark Technology Ltd opened.

1994 – Rural Environment Protection Scheme (REPS) launched.

1994 – Bord Bia created.

1994 – Scheme of Investment Aid for the Upgrading of On-Farm Dairying Facilities initiated.

1996 – ‘Cash-in-on-Grass’, ‘Responding to BSE’ and ‘Protein 3.50’ launched.

1997 – ‘Sheep 2-3-4’ unveiled.

1999 – Agenda 2000 amendments to CAP.

SHARING OPTIONS