It hardly needs to be mentioned that life is strange for a sports journalist during a time of a global pandemic.

Previously when asked about my work and its viability, especially for a freelancer that isn’t tied to any one organisation, the answer has been that there’ll always be matches to attend and that was the case until it wasn’t.

Still, don’t cry for me, Irish Country Living readers – the increase in free time has allowed other projects to receive the care and attention necessary.

By the time you read this, I will hopefully have finished, or be about to finish, the first draft of Believe, the autobiography of former Cork footballer Larry Tompkins.

The proof of ‘making it’ in the GAA is that you can be identified by just one name. Micko, DJ, Henry, for example, are guys who don’t need any more of an introduction. In Cork, Billy, Jimmy and Teddy stand out, among others, and so does Larry.

It’s probably hard to explain to someone who wasn’t there at the time, but the late 1980s were a transformative time for Cork football and the arrival of Tompkins was a catalyst for that. A Kildare native, he had fallen out with his home county’s county board in 1985 after he returned home from New York for a game only to find that those in charge wouldn’t pay for his flight back.

He might have remained in the Big Apple as the greatest footballer you never saw, but through playing for Donegal GFC, he came into contact with Corkmen Anthony and Vincie Collins, Martin O’Mahony and Martin Connolly, who spoke of a place where they take football as seriously as Larry did.

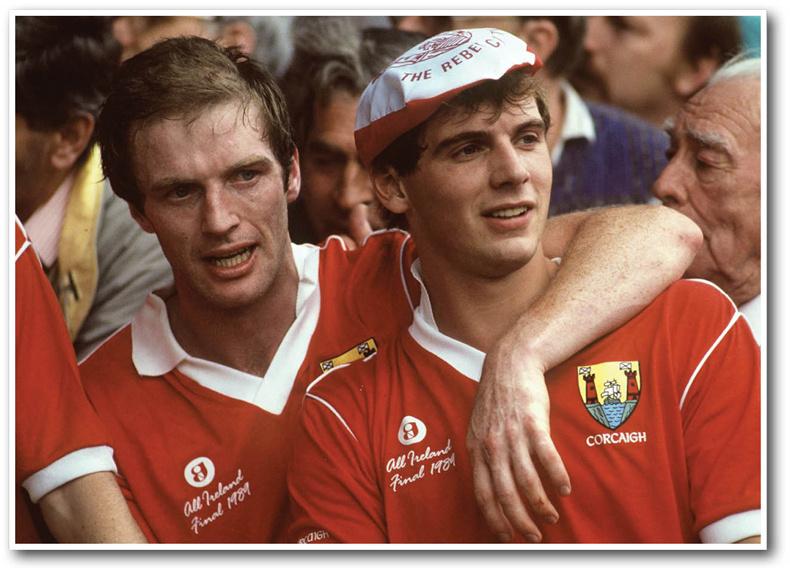

Tompkins, left, with John O’Driscoll after the 1989 All-Ireland final. \ Sportsfile

That place was Castlehaven and the course of Cork footballing history, at club and inter-county level, changed with his decision to throw his lot in with the Castletownshend/Union Hall club.

By any measure, he is an ideal candidate for an autobiography and I am exceedingly lucky to be the person to help tell that story. It’s perhaps odd that, of the Cork double-winning teams of 1990, only Teddy McCarthy and Billy Morgan have previously put pen to paper. There was also a fine tome produced last year by Adrian Russell entitled The Double and Larry’s contributions to that helped to bring the story to life. Now, the hope is that we can do justice to the rest of his life.

I have read many sporting autobiographies, some excellent and some not even worth looking at if your local second-hand shop was paying you to take it away. Almost always – albeit with notable exceptions, such as Joe Schmidt and Paul Galvin in recent times – a ghost-writer is used, as I am in this case. You might say that it makes the whole thing more synthetic and less true to life but – unsurprisingly – I would beg to differ.

Firstly, the reason that your favourite sportsperson isn’t writing his or her book themselves is because, rather than spending their time honing their writing skills, instead they spent it becoming the top-class athlete that made them a household name. Secondly – and this is something that Schmidt and Galvin arguably fell down on – a ghostwriter will ask questions that the subject may not necessarily ask him or herself.

The keys to producing something people want to read are honesty, which is obvious, and making sure you capture the voice of the person whose name is on the cover.

I have just finished reading Straight 8, by the recently retired New Zealand rugby captain Kieran Read. The All Black comes across as a stand-up guy, one who maximised his gifts and won it all, but the pacing and timing of the release were questionable. The book was obviously intended to be the crowning glory on a third straight World Cup win, with Read as captain; instead, it ends abruptly with a nine-page chapter on the World Cup, leaving him downbeat but somewhat phlegmatic, but realistically without being able to process it all.

In addition, Read is only just 34 – he has a lot of living to do yet. Larry Tompkins is nearly 57 and recounting his life at enough of a remove to analyse it properly.

The big area in which Read’s book struggles though is that his ghost, Scotty Stevenson, is a lovely writer but that comes across too much.

“It was a beautiful Northland affair, the scorching sun drying off the long grass in the hay paddocks, the pohutukawa in full crimson bloom above sand as white as bleached bones, the whirr and click of cicadas providing the seasonal soundtrack” – beautiful imagery, but we can say with almost cast-iron certainty that it’s not what Read felt when he saw such things.

There won’t be any florid language from Larry about a verdant Croke Park sward or mention of the crimson fire of the Cork jersey. Instead, it will be his words, as told to me in our many interviews going all the way back to last September.

Sometimes, the problem can be in finding enough worthwhile information to fill the allotted space; with Larry’s book, the issue is deciding what to cut, but it’s a nice headache. All going well, it will be in the shops come June. Hopefully, it will be worth the wait.

It hardly needs to be mentioned that life is strange for a sports journalist during a time of a global pandemic.

Previously when asked about my work and its viability, especially for a freelancer that isn’t tied to any one organisation, the answer has been that there’ll always be matches to attend and that was the case until it wasn’t.

Still, don’t cry for me, Irish Country Living readers – the increase in free time has allowed other projects to receive the care and attention necessary.

By the time you read this, I will hopefully have finished, or be about to finish, the first draft of Believe, the autobiography of former Cork footballer Larry Tompkins.

The proof of ‘making it’ in the GAA is that you can be identified by just one name. Micko, DJ, Henry, for example, are guys who don’t need any more of an introduction. In Cork, Billy, Jimmy and Teddy stand out, among others, and so does Larry.

It’s probably hard to explain to someone who wasn’t there at the time, but the late 1980s were a transformative time for Cork football and the arrival of Tompkins was a catalyst for that. A Kildare native, he had fallen out with his home county’s county board in 1985 after he returned home from New York for a game only to find that those in charge wouldn’t pay for his flight back.

He might have remained in the Big Apple as the greatest footballer you never saw, but through playing for Donegal GFC, he came into contact with Corkmen Anthony and Vincie Collins, Martin O’Mahony and Martin Connolly, who spoke of a place where they take football as seriously as Larry did.

Tompkins, left, with John O’Driscoll after the 1989 All-Ireland final. \ Sportsfile

That place was Castlehaven and the course of Cork footballing history, at club and inter-county level, changed with his decision to throw his lot in with the Castletownshend/Union Hall club.

By any measure, he is an ideal candidate for an autobiography and I am exceedingly lucky to be the person to help tell that story. It’s perhaps odd that, of the Cork double-winning teams of 1990, only Teddy McCarthy and Billy Morgan have previously put pen to paper. There was also a fine tome produced last year by Adrian Russell entitled The Double and Larry’s contributions to that helped to bring the story to life. Now, the hope is that we can do justice to the rest of his life.

I have read many sporting autobiographies, some excellent and some not even worth looking at if your local second-hand shop was paying you to take it away. Almost always – albeit with notable exceptions, such as Joe Schmidt and Paul Galvin in recent times – a ghost-writer is used, as I am in this case. You might say that it makes the whole thing more synthetic and less true to life but – unsurprisingly – I would beg to differ.

Firstly, the reason that your favourite sportsperson isn’t writing his or her book themselves is because, rather than spending their time honing their writing skills, instead they spent it becoming the top-class athlete that made them a household name. Secondly – and this is something that Schmidt and Galvin arguably fell down on – a ghostwriter will ask questions that the subject may not necessarily ask him or herself.

The keys to producing something people want to read are honesty, which is obvious, and making sure you capture the voice of the person whose name is on the cover.

I have just finished reading Straight 8, by the recently retired New Zealand rugby captain Kieran Read. The All Black comes across as a stand-up guy, one who maximised his gifts and won it all, but the pacing and timing of the release were questionable. The book was obviously intended to be the crowning glory on a third straight World Cup win, with Read as captain; instead, it ends abruptly with a nine-page chapter on the World Cup, leaving him downbeat but somewhat phlegmatic, but realistically without being able to process it all.

In addition, Read is only just 34 – he has a lot of living to do yet. Larry Tompkins is nearly 57 and recounting his life at enough of a remove to analyse it properly.

The big area in which Read’s book struggles though is that his ghost, Scotty Stevenson, is a lovely writer but that comes across too much.

“It was a beautiful Northland affair, the scorching sun drying off the long grass in the hay paddocks, the pohutukawa in full crimson bloom above sand as white as bleached bones, the whirr and click of cicadas providing the seasonal soundtrack” – beautiful imagery, but we can say with almost cast-iron certainty that it’s not what Read felt when he saw such things.

There won’t be any florid language from Larry about a verdant Croke Park sward or mention of the crimson fire of the Cork jersey. Instead, it will be his words, as told to me in our many interviews going all the way back to last September.

Sometimes, the problem can be in finding enough worthwhile information to fill the allotted space; with Larry’s book, the issue is deciding what to cut, but it’s a nice headache. All going well, it will be in the shops come June. Hopefully, it will be worth the wait.

SHARING OPTIONS