Politics wasn’t designed for women. Politics was established at a time when women were excluded. So the very norms, the rules, the culture of politics really favours the male lifestyle.”

Those are the words of Claire McGing, a politics researcher at Maynooth University, when she sat down with Irish Country Living to discuss the political landscape for women in Ireland.

Before we look to increasing the number of women in politics and creating a better sphere in which they can operate, we must first understand the past, stresses Claire, who is from a farming background.

“The electoral system, the ways parties operate, the way everything is set up, it goes back to a historic institutional perspective. That’s why people often complain more broadly beyond gender.

“People ask: ‘Why is politics so slow to change?’ Politics is slow to change because institutions are slow to change. It’s very slow, that’s politics, that’s parliament, any organisation that has been around a long time.”

Lie of the land

On Friday 24 May in the local and EU elections we will decide upon another wave of public representatives. Recent elections, both national and local, have shown an increase in female candidates running and taking seats.

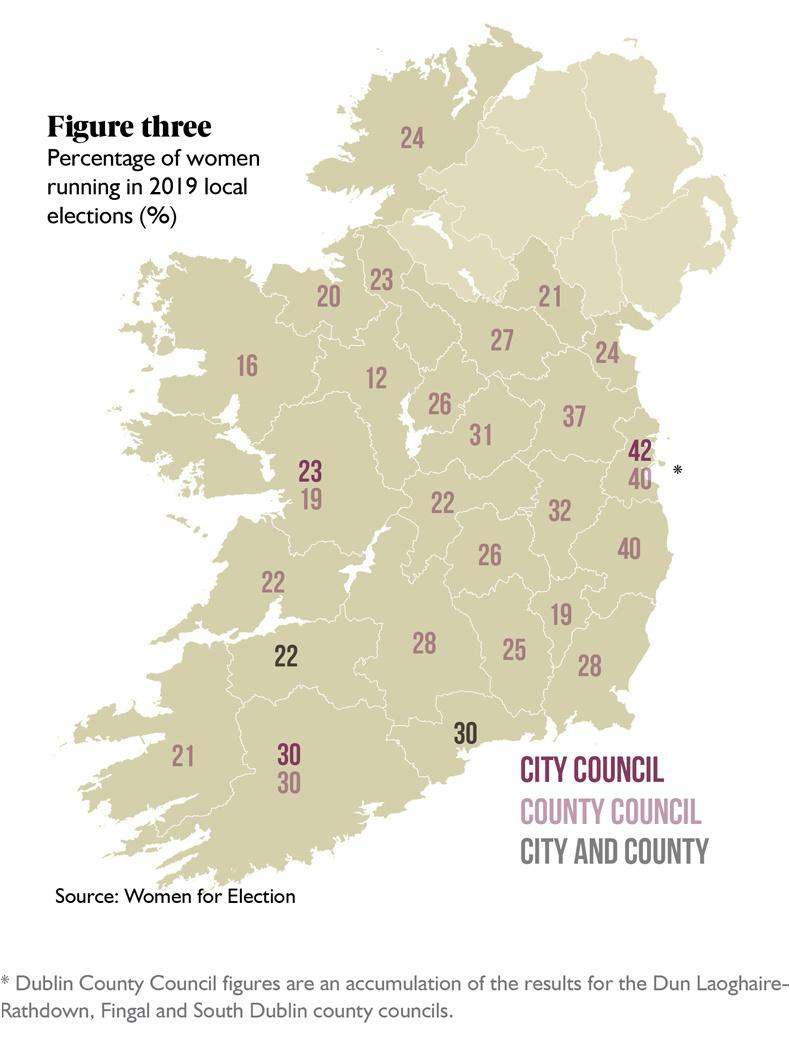

In the 2014 local elections, across the country 22% of candidates were female. From these, women went on to take 21% of seats. In this year’s local elections, just shy of 29% of candidates are women.

The fact that the percentage of women who ran in 2014 is virtually the same as the percentage of women elected shows that voters don’t distinguish on the basis of gender, explains Claire.

“The figures show that the proportion of women candidates was very low, well below the proportion of women in the population, but well below the proportion of women as party members as well.

“Across your four at least historical main parties – Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil, Labour and Sinn Féin –women counted for at least a third of members or more actually in some cases. So women were not coming through the party ranks to be selected as candidates in 2014.

“But, what it also shows is that when they are on the ballot paper, voters are not biased towards women. All things considered, the proportion of candidates is near matching the number of women taking seats. There’s no penalty to parties in running women, they should run women. You will ultimately argue that there’s no advantage to them running women either. Pragmatically speaking it’s neutral, it balances itself out.”

Women for Election

Ciairín de Buis is CEO of Women for Election, an organisation set up to provide training for and practical support to women who are thinking of running for politics. She agrees with Claire that gender does not influence voters’ decisions.

“We know from recent elections that when women run, they are just as likely to be elected as men. The barrier is getting women to run, getting women on to that ticket,” says Ciairín.

The obstacles to women running for election are described as the five Cs: cash, culture, confidence, childcare and (selection) conventions. “Our focus is on confidence, around equipping and inspiring women to run, and to run successfully.

“We provide training in three key areas: communications, confidence and campaigning,” explains the CEO, who is originally from Co Kerry.

“One of the things we have seen and recognise is the need for a woman to feel fully confident in her own abilities before she will put herself forward. That’s what our training does.”

From the ground up

To see more women in politics and for them to progress up the ranks, local elections are crucial, says Claire. Three-quarters of TDs have sat on councils at some stage of their political lives.

“It’s more significant for women than it is for men, women are more likely statistically to need local government experience to become deputies, because they have to build a base to get elected. That means, because there are so few of them (female councillors) in rural Ireland, there’s no pipeline for women to progress into the Dáil from rural Ireland.”

Gender quotas were introduced for the first time in the 2016 general election. Political parties had to run 30% women candidates or face a sanction to their electoral funding.

From this there was a massive increase in female candidacy levels and a record number of 35 female TDs were elected to the Dáil, 22% of sitting TDs. Of these 35, 26 were in Dublin and the rest of Leinster, meaning that only nine were elected across Munster, Connacht and Ulster.

Both recent national and local elections show an urban/rural divide in relation to women in politics. “The north-west statistically speaking is one of the worst regions in the country, but having said that there are parts of Munster that are not great either,” says Claire.

Interestingly, when contrasting the local or national elections with the European elections, the percentage of female candidates is much higher. In this year’s elections to the European Parliament, 47% of candidates in Dublin, 39% of candidates in the south and 35% of candidates in the midlands-northwest are women.

There are a number factors in this, says Claire. Firstly, European elections are more like “mini-presidential elections”, in that there is a culture of high-profile people running, making it easier for women to get on the ballot paper. Secondly, geographically the constituencies are much bigger, particularly in the south and midlands-northwest. Meaning they take in rural, urban and commuter areas, which all have varying levels of female representation at local and national level.

Leadership

In getting more women running and elected in areas where representation is low, both the Government’s policy around women in politics and the parties’ attitudes within these constituencies is key, reflects Claire.

“There’s another layer even before councils; who emerges into leadership positions in your party branch? Who’s the chair? Who’s the secretary?

“They can often be highly gendered, because the chair has the power, but the secretary does a lot of the functional work. The data we have from a number of years ago shows that women are much more likely to be the secretary of a party branch, rather than the chair. The chair also often identifies candidates and they identify candidates within their own networks, that tend to be male.”

The general election constituency of Limerick county, formerly Limerick west, has never elected a woman to the Dáil. The last time a woman contested a general election here was 1997. Two women ran that year; Mary Kelly, Labour, and Jeanette McDonnell, Progressive Democrats.

Mary Kelly is a former councillor and senator from Newcastle West, Co Limerick. She was a sitting councillor from 1991-1999 on what was then Limerick County Council for the Newcastle West municipal district. She ran in both the 1992 and 1997 general elections and was elected to the Seanad in 1993.

Speaking with Irish Country Living, Mary discusses what political life was like for her and what can be done to get more female politicians in rural areas.

The catalyst

There were a number of social issues that prompted Mary to get involved in the Labour Party in the 1980s, despite the fact that her father was a Fianna Fáil man. She felt strongly about the ban on contraceptives and divorce, and wanted to see change in these areas. It also didn’t sit well with her that when she went to take out a Credit Union loan she needed her husband’s permission, despite the fact that she had her own salary as a teacher.

The late Jim Kemmy, a former Labour TD in Limerick, was a big promoter of women in the party. He encouraged Mary to stand for local election, as he did with Jan O’Sullivan and others.

“We were known as Kemmy’s femmies,” Mary says. “He deliberately went out to see if there was an able woman active in the party and he said, ‘You should go, you should stand’. It’s important to have someone like that. To have someone of Jim’s stature and vision promoting you meant a great deal.”

Woman in the bookshop

It was the strength of second preference votes that got Mary elected to Limerick County Council, coupled with the fact that many women in the area knew Mary, a mother of six, from buying school books in her shop.

“At that time I had opened up my own bookshop, and as you know the job of buying school books rests a great deal with the woman of the house. So I was a household name to many of the families in west Limerick. When I would come to the door I’d get, ‘Oh, you’re the woman in the bookshop’.

I only got elected, to be perfectly honest with you, on the strength of second preference votes

“At first the pundits in the public houses would say: ‘Sure nobody knows her.’ They forgot that the other half of the house’s vote counts for exactly the same as theirs. When I was elected it was the tart commentary, ‘Oh sure it was the women elected her’ – in other words, I was a second-class councillor as well as a second-class citizen.

“I only got elected, to be perfectly honest with you, on the strength of second preference votes. I figured an awful lot of local women voted maybe for their party first and then I got the number two.”

Political life

At the time Mary was one of only three women on Limerick County Council, as well as being the sole Labour councillor. This compounded a difficult atmosphere. Many of her male colleagues were gentlemen, but some less so.

“Particularly when I was elected to the Seanad in 1993 (you could be both a councillor and a senator at the time). I felt it was knives out by some in Limerick County Council. It was obvious to me that there were some with an intention to ‘bring her down’.

“That was the toughest part of the job – it wasn’t meeting the people, it wasn’t doing the work for the people, it wasn’t actually going to meetings; it was that you knew when you stood up and said something there was sniggering, there was laughing, there was bad behaviour.”

Mary expresses that thankfully local politics has moved on from this.

In the upcoming local elections there is no woman standing in her area, the Newcastle West municipal district.

“I think there has to be a decision by the parties’ headquarters to promote women into positions of power within the party structures. They’ll have to be proactive in spotting talent, going out and getting her involved. Women are not just for making tea.”

Mary did not seek re-election in 1999.

SHARING OPTIONS