B y the time you have read this sentence, 40,000 Coca-Cola products will have been consumed around the world. A total of 1.9 billion servings of Coke alone are consumed every day in all but two countries around the world. It has been said the company’s vision is that Coke will some day flow from the kitchen tap.

Although the company name may lead you to think that it sells just one or two drinks, Coca-Cola has a product portfolio of more than 3,500 beverages with 500 brands, spanning water to energy drinks. It owns 17 of the 33 non-alcoholic billion-dollar brands – a brand that sells in excess of $1bn.

Coca-Cola is the best example of the power of branding. What was invented as a cough syrup has grown into a $47bn turnover company, with the Coca-Cola brand alone worth an estimated $79.2bn.

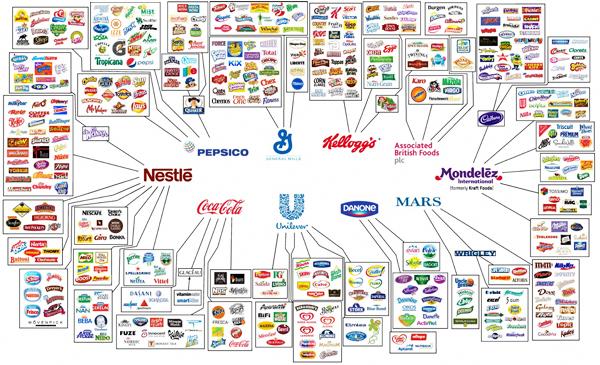

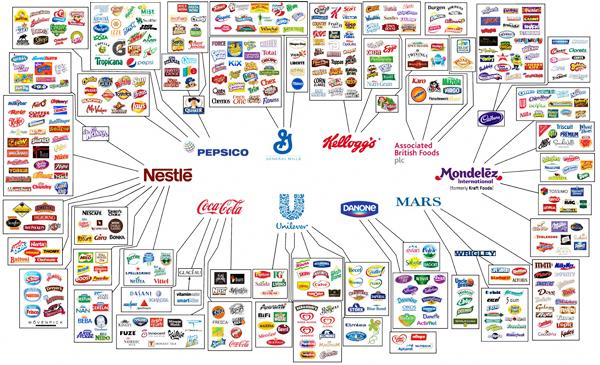

Ten mega food and drink producers control almost everything we buy from mayonnaise to coffee to cereals. Because of pressure from retailers, the food-producing sector has consolidated to the point where a handful of corporations produce the majority of the products on our supermarket shelves.

For example, the $200bn corporation Nestlé, the biggest food company in the world, owns nearly 2,000 different brands and employs 333,000 people. The corporate colossus, based in Geneva, sells over one billion products every day, with worldwide sales totalling $105bn last year. From Nescafé to KitKat, its products can be found on almost every aisle in supermarkets around the planet.

Unilever, with foundations in soap and butter (both fats), has 14 billion-dollar brands, which make up more than 54% of its business. The company behind the brands HB and Ben & Jerry’s had a turnover of $50bn in 2013. These large food producers have the ability to supply large volumes and varieties of products. The smaller, innovative food companies often have difficulty getting onto supermarket shelves or they get pushed off due to difficult contract terms or the low prices offered.

Of the new food companies that survive, many end up being bought out by the largest manufacturers. For example, last year, Cully & Sully, the Cork-based artisan food producer, was bought by the $2bn organic food specialist, Hain Celestial, for a deal worth an estimated €15m. Recently, we have seen large food company mergers and acquisitions. Kellogg’s became the world’s second-largest snack food company (after PepsiCo) by acquiring the Pringles brand from Procter & Gamble for $2.7bn. We also saw Kraft buy out Cadbury in 2010 for $18.5bn, while Bright Foods bought Weetabix.

Unilever has grown through acquisitions of well-known household brands to the point where two billion people now use one of the company’s products on any given day. It owns Slim Fast, Flora, Knorr, Colman’s Mustard and, in the second-largest cash acquisition in history, it acquired Hellman’s in 2000.

Route to market

These companies are key to Ireland’s success as a food exporter. Many Irish agribusinesses depend on these billion-dollar brand food producers to provide a route to market. For example, Dairygold is the third largest supplier of dairy ingredients to Danone’s infant formula division worldwide.

Cadbury, part of the food giant Mondelez, sources 80 million litres of milk annually from Kerry, Boherbue and Lee Strand for use in the manufacture of its chocolate crumb.

Other bluechip customers that are an important route to market for Irish produce include McDonald’s for Dawn Meats, Nestlé for Lakeland and Starbucks for Aryzta.

Foodopoly

The major food companies can be seen in every shopping aisle all over the world. Even in developing countries like Nigeria, the coffee, cereal and dairy aisles are dominated by Nestlé. While the Nescafé coffee brand is well known here, it has only 4% of the US coffee market. This is in contrast to the other categories where it dominates, including 73% in baby food, the leading position in pizzas, 41% in bottled water and 34% in frozen meals.

A recent US study found that the top companies controlled an average of 63% of the sales of 100 types of groceries. For example, Kellogg’s, General Mills, PepsiCo and Post Foods control 80% of cereal sales, making shoppers hard-pressed to find a box of cereal that isn’t owned by one of the big companies.

The choice that consumers have in the cereal aisle comes largely from the variation of the big companies’ brands they select.

In the fridge, Unilever controls 24% of the butter/margarine market with brands like I can’t Believe It’s Not Butter. Danone, with brands like Activia, holds 30% of the yoghurt market, while General Mills holds 30% with Yoplait.

Similarly, in Ireland, five brands owned by three companies control 86% of the carbonated soft drinks market – Coca-Cola, Pepsico and C+C. In the cereal aisle, five brands owned by three companies control 41% of the breakfast cereal market – Weetabix, Flahavan’s and Kellogg’s. Coca-Cola remains the largest selling brand in Irish grocery, retaining a 10-year position at the top, while Avonmore is the second largest brand in Ireland.

Almost 50% of the top 100 brands bought in Ireland are owned by the billion-dollar food producers.

The rise of own label

Brands today are fighting a tough battle with the new shopper and the emergence of private label. Being a well-established brand is not necessarily enough anymore – even the mighty Coca-Cola is regularly engaged in multibuy deals in all the major multiples.

The popularity and market share of own-brand products has grown strongly in recent years.

Own-brand labels are growing at 2.3% year-on-year as shoppers try to make savings. They account for 47% of the retail market today in Ireland.

The reasons are twofold as price-conscious consumers opt for cheaper alternatives and, in response to this demand, the quality of the products has increased dramatically.

With 150 million people entering the wealthy middle class every year in emerging markets like China and Africa, these big-brand food producers are focusing their attention on these areas. For example, 57% of Unilever’s turnover now comes from emerging markets.

Brand investment

To maintain their position at the top, these companies spend heavily on advertising. For example, Coca-Cola spends about $2.6bn per year on advertising, equivalent to 5% of turnover. No wonder the logo is recognised by 94% of the world’s population. Industry analysts say their competitor PepsiCo will spend $1.7bn this year on marketing its beverages, up 50%.

Amazingly, Unilever spent the same amount on advertising last year as the turnover of the Kerry group – $8bn.

And the spending doesn’t stop there. These companies invest heavily in R&D to develop new products to ensure consumers continue to choose their brands.

Last year, for example, Unilever spent $1.4bn on R&D, while Nestlé invests around $1.7bn in R&D every year.

Kellogg’s, too, invests heavily in its brands, spending more than $1bn annually on advertising. In the 1980s, the US market share of Kellogg’s hit a low of 37% and analysts called it “a fine company that’s past its prime” and stated that the breakfast cereal market was “mature”. In effect, it had not spent enough on advertising and R&D. It then switched its focus and emphasised cereal’s convenience and nutritional value, persuading consumers to eat 26% more cereal.

The Kerrygold brand, with retail sales of €0.5bn globally, had record sales with 350m packets sold worldwide in 2013. It remains the number one brand in Germany, with a 17% market share and 55% branded share. In the UK, it had its highest market share in 20 years and held the number three position. In Ireland, it is the number one selling butter brand.

IDB invested €36m in the Kerrygold brand in 2013. The brand was created in 1962 and is Ireland’s only truly internationally-known food brand. The brand originally started out with butter but it has now expanded into products such as cheese and milk powder. The IDB has made significant investments in R+D, for example, producing a new spreadable butter under the Kerrygold brand.

According to Kevin Lane, CEO of the Irish Dairy Board: “While brands chase the market on the up, when prices are rising, they lag it on the way down and this is when the real power and value of a brand comes into play.”

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: