“I had nothing but the truth and facts the whole time. Wrong is wrong and it can’t be made right. You can’t say it wasn’t wrong because it happened years ago. It was wrong.”

Those are the words of Catherine Corless. A woman who needs no introduction. The local historian and farmer from Co Galway, who despite obstacles in her way at every turn, uncovered and brought to light an unmarked mass grave containing hundreds of babies in a disused sewage tank on the old site of the Tuam Mother and Baby Home.

Before going to meet Catherine at her home outside Tuam, I visit the site where the babies are buried. I’ve been given directions. I follow them exactly. However, driving around the block of the housing estate for the fifth time, I start to think, I must have gone wrong.

Then I finally see it, a narrow road between two houses. Just enough room to fit a car. As the space opens up in front of me, again I think, this can’t be it. But the playground is there as described, big and eerie. Weeds and moss grow up through the surface, broken glass in the middle of it. No one comes the whole time I’m there. A swing in the corner sways and creeks in the winter breeze.

At the far side of the playground there’s a walled-off grassy plot. The apology from the Bon Secours Sisters, who ran the home, is laminated on an A4 sheet and tie-wrapped to the gate. I’m conscious that I’m walking on bodies.

On the wall is a noticeboard with the names of the 796 children born here whose burial records are missing. The noticeboard is fading now. Annie Begley died in 1938 aged three months.

There’s a grotto with a statue of Our Lady in the corner. All along the wall people have left tributes to the Tuam Babies – flowers, balloons, teddies and even a toy tractor.

At the beginning of this year the report from the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes came out, a six-year investigation into what happened in these institutions. Last week a redress scheme was announced. Both were met with strong disappointment from survivors.

In getting to this point, Catherine has worked for over a decade. The events in full since Catherine started this journey in 2010 certainly won’t fit within the parameters of these pages. They’re contained in her new book Belonging, nominated for Biography of the Year at the upcoming An Post book awards. The royalties from the book are going to Tír na nÓg Orphanage.

To understand what Catherine has done for the Tuam Babies, first we must understand a little about the woman herself.

Private past

Catherine grew up on a farm on the edge of Tuam. She always helped out. When she and her husband Aidan took over the running of his family beef and sheep farm, now their family farm, Catherine took on the majority of the work. Aidan says so himself as we chat in their kitchen.

Aidan was a salesman. Catherine always had and still has a love of the outdoors and farming. Also, Catherine has anxiety and is an introvert. She can find social situations difficult and so working at home on the farm suited her.

Catherine’s story with the Tuam Babies largely begins with her own mother. From her early years, Catherine knew her mother was withholding something from the family and was distant. She was from Armagh and didn’t speak about her family. Catherine wanted to know what was behind this.

Later in life, after her mother passed away, Catherine began to research her mother’s past. She found out she was, for want of far better words, ‘illegitimate’/‘born out of wedlock’, and had been fostered.

“I got in my mother’s bad books as a child, because I would press her,” Catherine recalls. “I was always asking her why she was in bad form. It annoyed her twice as much when I’d notice her bad form. She’d be away in her own mind, frustrated and kind of distant.

“I think that put a huge gap between us, because it irritated her a lot. She’d never sit down and explain anything to you or have time with you. Anything affectionate was out. She couldn’t handle that.

“I’d see mothers coming to school, picking up their kids and fussing over them. I was saying to myself, why can’t she be like that? She’d never take you even up in her lap or anything. She couldn’t because she hadn’t the knowhow. She hadn’t that herself, she never had it. I had a pain to find out why on Earth was she like that. When I found out, that was a breakthrough for me.”

Discovering her mother’s background had a profound effect on Catherine. Things made sense for her finally. This is part of the reason she goes to such lengths to help other people find out about their past through DNA and acquiring records, she knows the difference it will make to them.

“I think I blamed myself a lot for irritating my mother. I really blamed myself for being a pest and it was a healing in myself when I discovered her background. That’s why I’d be trying so hard for survivors; to help them make sense of their own lives, what they missed out on and what they should have had.

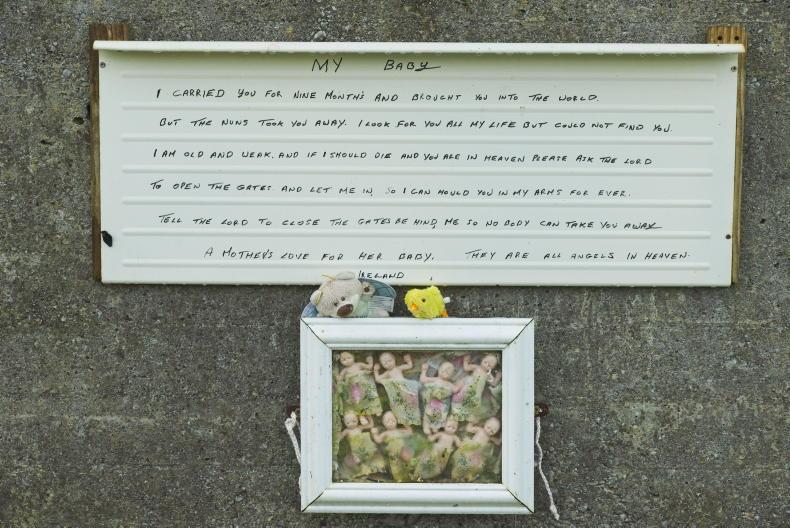

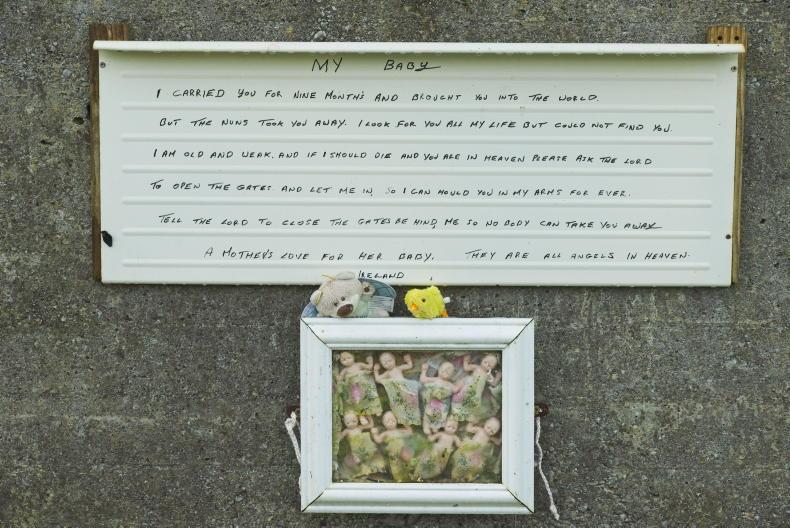

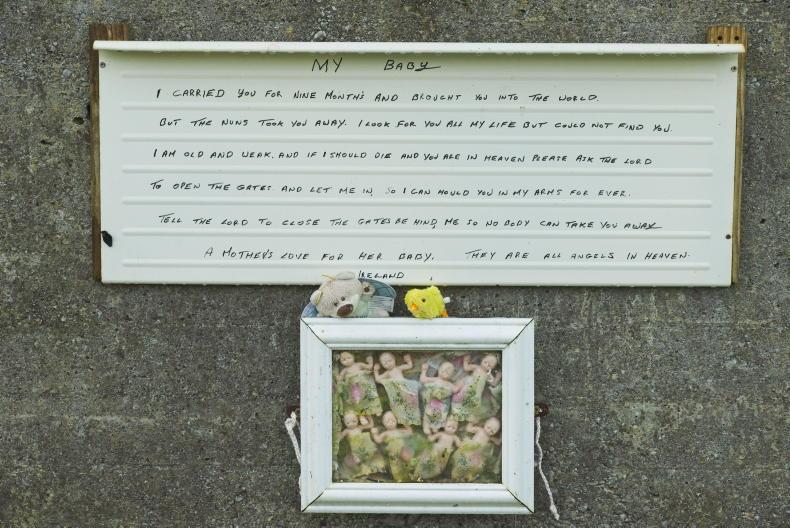

Soft toys left at the old site. \ David Ruffles

“I keep saying to them, ‘It’s not yer fault, it’s not yer shame, it’s not yer mother’s shame. Put the blame back on where it came from, back on the Church and back on society and back on authorities. Ye were totally innocent children, just remember that. And your mother was innocent as well. In her own way she was condemned and made give you up.’”

Shared past

Catherine’s research skills were honed while looking into her mother’s background. After this she decided to take a local history class, once a week for a year. She became captivated by different ways to find out information. This got her into local history.

She was approached by the Journal of the Old Tuam Society (JOTS). The editor had read some of what she wrote for the course and asked would she like to contribute. She decided to do an essay on the Tuam Mother and Baby home.

Her research for this was meticulous. In the 1970s, the aforementioned housing estate was built on the site of the home. She started by knocking on doors there. She heard stories of people finding bones in an unmarked grave in the plot behind the playground where the grotto is.

At the beginning of this year the report from the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes came out, a six-year investigation into what happened in these institutions. Last week a redress scheme was announced. Both were met with strong disappointment from survivors. \ David Ruffles

She acquired birth certs for some of the children who had died in the home and found no burial records for them. Maps she accessed at the National University of Galway (NUIG) showed there was an old sewage tank where the bones were known to be.

Catherine printed this revelation in her essay in the JOTS, and then, nothing.

No one contacted her about it. But she couldn’t let it go, so she kept digging. She went on to buy the birth cert of every child on record who died in the home, 798 of them, she found out. She checked the ledgers for graveyards in Galway and Mayo. Two of these children showed as being buried in these graveyards, both were orphans.

This led her to be certain that these bones were not Famine bones as it had been said, but the remains of the ‘illegitimate’ children who died in the home.

Eventually the story gathered traction and was broken in the Mail on Sunday in 2014. It blew up instantly. From the silence her initial essay was met with, the story was suddenly attracting international attention.

Liam Neeson

I am by no means the first journalist to sit at this table. Catherine and Aidan laugh that the china I’m drinking from was bought for Liam Neeson, who is making a film based on the Tuam Babies scandal.

“Since 2014 in this kitchen there have been whole gangs of them coming and going – journalists, documentary makers,” Catherine says. “What amazed me was the interest outside Ireland. They were here from America. Al Jazeera, I didn’t expect them to come, they covered it very well. It just shows you the extent of people that were on to me. They came from Iceland, Australia, all the European countries and Northern Ireland.

Tributes left at the old site of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co Galway. \ David Ruffles

“I was happy to facilitate everyone who came this way, because only for that it would have died a quick death. I was about a year here trying to get it out in Tuam, whereas the story should have opened up immediately.”

When the story first broke in the national media, Catherine thought that would be the end of the road for her. People would co-operate and the right things would be done. Aidan was a bit more apprehensive. There have been many bumps in the road since in trying to get what both Catherine and the survivors want, the babies to be exhumed and reburied, which has still not happened.

“What’s not coming out is that there’s shuttering between the chambers and the tank, which means those chambers were designed to take the effluent from the tank. They’re inclined to keep that quiet, that it’s proven beyond doubt that’s where they put them,” Catherine says.

“That’s what the archaeologist found. Their remains are mingled, unfortunately because of all of the flood water coming in on top of them, swishing them around the place. It’s a horror story. The poor little things. Even Canon Law, their law, says that babies who are baptised get a Christian burial. That didn’t happen and there’s no fuss about that at all.”

Last week the redress scheme for survivors of mother and baby homes was announced by Minister for Children, Rodric O’Gorman. While it’s something she isn’t directly working on, Catherine supports people’s needs for redress. No redress was offered for babies and children who spent six months or less in a mother and baby home. She feels this is disrespectful.

“Rodric O’Gorman brought in that the baby up to six months didn’t matter. I think that has to be squashed, really and truly. The very beginning of a baby and mother, that’s the most important few minutes. Even when they’re born, they lay the little baby on your stomach to feel the closeness, to bond with the baby. To say that any baby under six months wouldn’t be affected, it just goes to show they haven’t a clue as regards humanity.”

Last year Catherine and Aidan met with Minister O’Gorman, who said he is currently in the process of passing legislation to allow for mass exhumation of the babies’ remains. She was told the bill should be passed by the end of the year and work should begin in early 2022. A special technical report has already been completed on how to exhume the babies.

Justice

Until then, we will have to wait and see. What is certain, however, is that the woman who started this won’t stop until she sees it through. A woman with a vast sense of justice and who kept her love of babies and children at the centre of this investigation always.

“They’re just a joy. The little bit of devilment and happiness in them, it bounces off them. The glee, the happiness and the innocence of them. That’s what tortures me, especially when I hold the youngest of the grandchildren, to think of parting with him after rearing him for a year. The savagery of that. How could a mother get over that? She never could.

“That’s savagery that went on. That’s what keeps me going. It was wrong. It was horrible. The fact that they didn’t want to do something about it and that fact that they tried to cover it up again, that must be the most hurtful thing I ever felt.”

The Tuam Babies, may they rest in peace. When will they rest in peace?

Read more

Damien’s Diary: Ireland’s greatest shame and atrocity

“I had nothing but the truth and facts the whole time. Wrong is wrong and it can’t be made right. You can’t say it wasn’t wrong because it happened years ago. It was wrong.”

Those are the words of Catherine Corless. A woman who needs no introduction. The local historian and farmer from Co Galway, who despite obstacles in her way at every turn, uncovered and brought to light an unmarked mass grave containing hundreds of babies in a disused sewage tank on the old site of the Tuam Mother and Baby Home.

Before going to meet Catherine at her home outside Tuam, I visit the site where the babies are buried. I’ve been given directions. I follow them exactly. However, driving around the block of the housing estate for the fifth time, I start to think, I must have gone wrong.

Then I finally see it, a narrow road between two houses. Just enough room to fit a car. As the space opens up in front of me, again I think, this can’t be it. But the playground is there as described, big and eerie. Weeds and moss grow up through the surface, broken glass in the middle of it. No one comes the whole time I’m there. A swing in the corner sways and creeks in the winter breeze.

At the far side of the playground there’s a walled-off grassy plot. The apology from the Bon Secours Sisters, who ran the home, is laminated on an A4 sheet and tie-wrapped to the gate. I’m conscious that I’m walking on bodies.

On the wall is a noticeboard with the names of the 796 children born here whose burial records are missing. The noticeboard is fading now. Annie Begley died in 1938 aged three months.

There’s a grotto with a statue of Our Lady in the corner. All along the wall people have left tributes to the Tuam Babies – flowers, balloons, teddies and even a toy tractor.

At the beginning of this year the report from the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes came out, a six-year investigation into what happened in these institutions. Last week a redress scheme was announced. Both were met with strong disappointment from survivors.

In getting to this point, Catherine has worked for over a decade. The events in full since Catherine started this journey in 2010 certainly won’t fit within the parameters of these pages. They’re contained in her new book Belonging, nominated for Biography of the Year at the upcoming An Post book awards. The royalties from the book are going to Tír na nÓg Orphanage.

To understand what Catherine has done for the Tuam Babies, first we must understand a little about the woman herself.

Private past

Catherine grew up on a farm on the edge of Tuam. She always helped out. When she and her husband Aidan took over the running of his family beef and sheep farm, now their family farm, Catherine took on the majority of the work. Aidan says so himself as we chat in their kitchen.

Aidan was a salesman. Catherine always had and still has a love of the outdoors and farming. Also, Catherine has anxiety and is an introvert. She can find social situations difficult and so working at home on the farm suited her.

Catherine’s story with the Tuam Babies largely begins with her own mother. From her early years, Catherine knew her mother was withholding something from the family and was distant. She was from Armagh and didn’t speak about her family. Catherine wanted to know what was behind this.

Later in life, after her mother passed away, Catherine began to research her mother’s past. She found out she was, for want of far better words, ‘illegitimate’/‘born out of wedlock’, and had been fostered.

“I got in my mother’s bad books as a child, because I would press her,” Catherine recalls. “I was always asking her why she was in bad form. It annoyed her twice as much when I’d notice her bad form. She’d be away in her own mind, frustrated and kind of distant.

“I think that put a huge gap between us, because it irritated her a lot. She’d never sit down and explain anything to you or have time with you. Anything affectionate was out. She couldn’t handle that.

“I’d see mothers coming to school, picking up their kids and fussing over them. I was saying to myself, why can’t she be like that? She’d never take you even up in her lap or anything. She couldn’t because she hadn’t the knowhow. She hadn’t that herself, she never had it. I had a pain to find out why on Earth was she like that. When I found out, that was a breakthrough for me.”

Discovering her mother’s background had a profound effect on Catherine. Things made sense for her finally. This is part of the reason she goes to such lengths to help other people find out about their past through DNA and acquiring records, she knows the difference it will make to them.

“I think I blamed myself a lot for irritating my mother. I really blamed myself for being a pest and it was a healing in myself when I discovered her background. That’s why I’d be trying so hard for survivors; to help them make sense of their own lives, what they missed out on and what they should have had.

Soft toys left at the old site. \ David Ruffles

“I keep saying to them, ‘It’s not yer fault, it’s not yer shame, it’s not yer mother’s shame. Put the blame back on where it came from, back on the Church and back on society and back on authorities. Ye were totally innocent children, just remember that. And your mother was innocent as well. In her own way she was condemned and made give you up.’”

Shared past

Catherine’s research skills were honed while looking into her mother’s background. After this she decided to take a local history class, once a week for a year. She became captivated by different ways to find out information. This got her into local history.

She was approached by the Journal of the Old Tuam Society (JOTS). The editor had read some of what she wrote for the course and asked would she like to contribute. She decided to do an essay on the Tuam Mother and Baby home.

Her research for this was meticulous. In the 1970s, the aforementioned housing estate was built on the site of the home. She started by knocking on doors there. She heard stories of people finding bones in an unmarked grave in the plot behind the playground where the grotto is.

At the beginning of this year the report from the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes came out, a six-year investigation into what happened in these institutions. Last week a redress scheme was announced. Both were met with strong disappointment from survivors. \ David Ruffles

She acquired birth certs for some of the children who had died in the home and found no burial records for them. Maps she accessed at the National University of Galway (NUIG) showed there was an old sewage tank where the bones were known to be.

Catherine printed this revelation in her essay in the JOTS, and then, nothing.

No one contacted her about it. But she couldn’t let it go, so she kept digging. She went on to buy the birth cert of every child on record who died in the home, 798 of them, she found out. She checked the ledgers for graveyards in Galway and Mayo. Two of these children showed as being buried in these graveyards, both were orphans.

This led her to be certain that these bones were not Famine bones as it had been said, but the remains of the ‘illegitimate’ children who died in the home.

Eventually the story gathered traction and was broken in the Mail on Sunday in 2014. It blew up instantly. From the silence her initial essay was met with, the story was suddenly attracting international attention.

Liam Neeson

I am by no means the first journalist to sit at this table. Catherine and Aidan laugh that the china I’m drinking from was bought for Liam Neeson, who is making a film based on the Tuam Babies scandal.

“Since 2014 in this kitchen there have been whole gangs of them coming and going – journalists, documentary makers,” Catherine says. “What amazed me was the interest outside Ireland. They were here from America. Al Jazeera, I didn’t expect them to come, they covered it very well. It just shows you the extent of people that were on to me. They came from Iceland, Australia, all the European countries and Northern Ireland.

Tributes left at the old site of the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co Galway. \ David Ruffles

“I was happy to facilitate everyone who came this way, because only for that it would have died a quick death. I was about a year here trying to get it out in Tuam, whereas the story should have opened up immediately.”

When the story first broke in the national media, Catherine thought that would be the end of the road for her. People would co-operate and the right things would be done. Aidan was a bit more apprehensive. There have been many bumps in the road since in trying to get what both Catherine and the survivors want, the babies to be exhumed and reburied, which has still not happened.

“What’s not coming out is that there’s shuttering between the chambers and the tank, which means those chambers were designed to take the effluent from the tank. They’re inclined to keep that quiet, that it’s proven beyond doubt that’s where they put them,” Catherine says.

“That’s what the archaeologist found. Their remains are mingled, unfortunately because of all of the flood water coming in on top of them, swishing them around the place. It’s a horror story. The poor little things. Even Canon Law, their law, says that babies who are baptised get a Christian burial. That didn’t happen and there’s no fuss about that at all.”

Last week the redress scheme for survivors of mother and baby homes was announced by Minister for Children, Rodric O’Gorman. While it’s something she isn’t directly working on, Catherine supports people’s needs for redress. No redress was offered for babies and children who spent six months or less in a mother and baby home. She feels this is disrespectful.

“Rodric O’Gorman brought in that the baby up to six months didn’t matter. I think that has to be squashed, really and truly. The very beginning of a baby and mother, that’s the most important few minutes. Even when they’re born, they lay the little baby on your stomach to feel the closeness, to bond with the baby. To say that any baby under six months wouldn’t be affected, it just goes to show they haven’t a clue as regards humanity.”

Last year Catherine and Aidan met with Minister O’Gorman, who said he is currently in the process of passing legislation to allow for mass exhumation of the babies’ remains. She was told the bill should be passed by the end of the year and work should begin in early 2022. A special technical report has already been completed on how to exhume the babies.

Justice

Until then, we will have to wait and see. What is certain, however, is that the woman who started this won’t stop until she sees it through. A woman with a vast sense of justice and who kept her love of babies and children at the centre of this investigation always.

“They’re just a joy. The little bit of devilment and happiness in them, it bounces off them. The glee, the happiness and the innocence of them. That’s what tortures me, especially when I hold the youngest of the grandchildren, to think of parting with him after rearing him for a year. The savagery of that. How could a mother get over that? She never could.

“That’s savagery that went on. That’s what keeps me going. It was wrong. It was horrible. The fact that they didn’t want to do something about it and that fact that they tried to cover it up again, that must be the most hurtful thing I ever felt.”

The Tuam Babies, may they rest in peace. When will they rest in peace?

Read more

Damien’s Diary: Ireland’s greatest shame and atrocity

SHARING OPTIONS