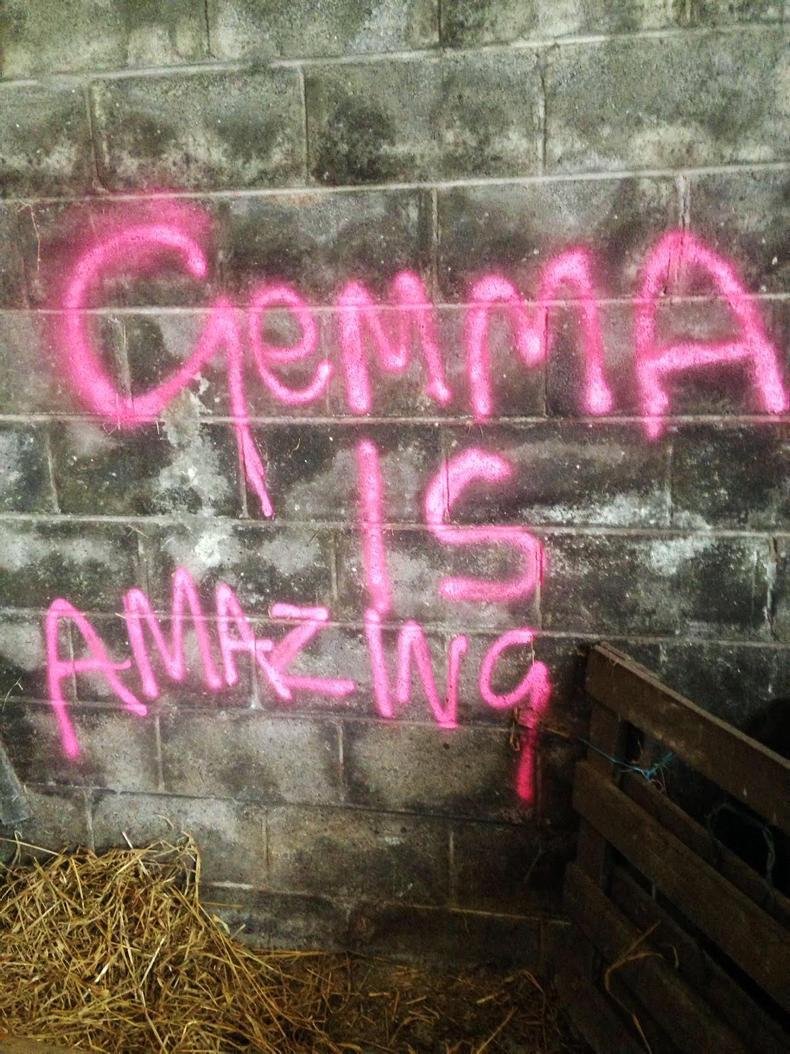

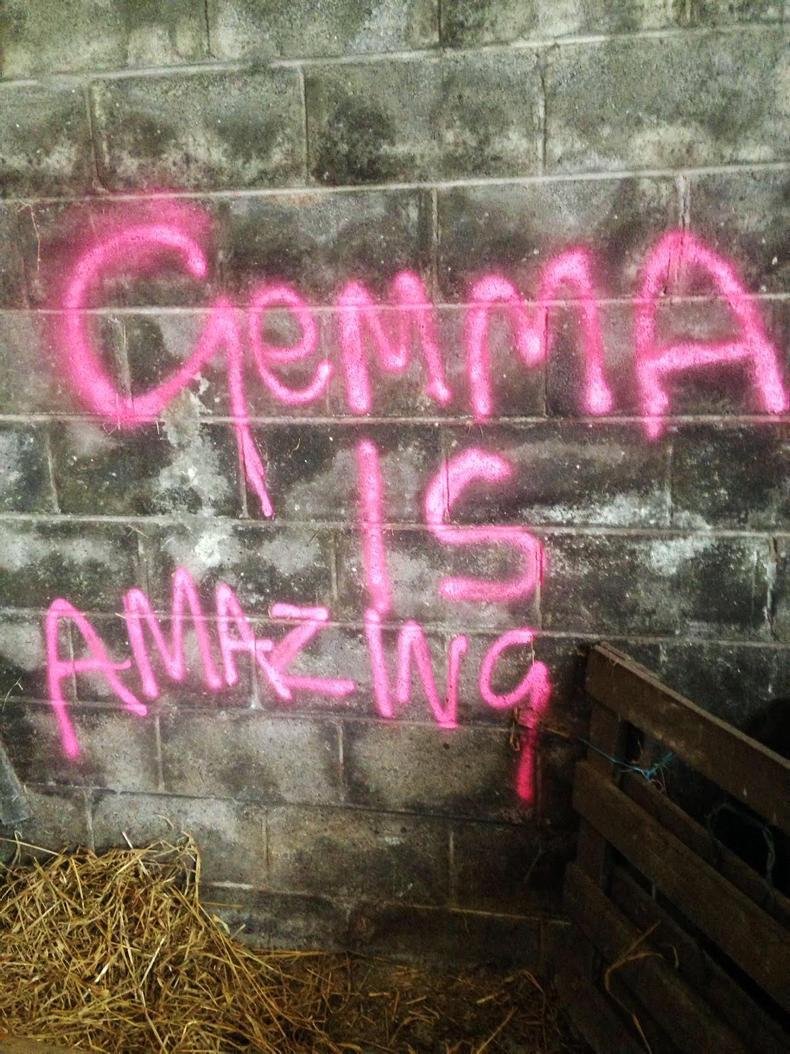

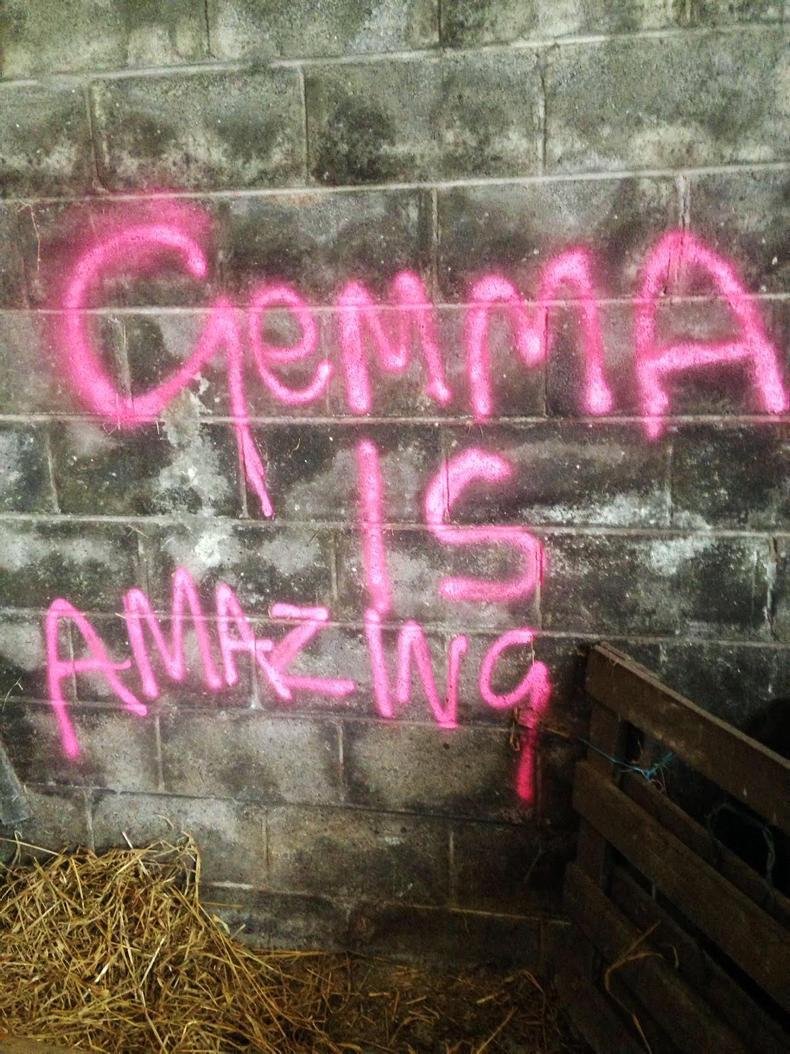

The words “Gemma Is Amazing” are written on a sheep shed wall on the Willis farm in Tullow, Co Carlow. The statement, in pink fluorescent paint, is the first thing you see when you open the door. The words bear testimony to the wonderful recovery from a very serious car accident of Gemma Willis, now 25.

Gemma Willis.

Focusing on the positive

Gemma Willis has big plans for 2020. She will be sailing on a Tall Ship from Cadiz to Lisbon as part of the Parade of Sails race and she will be part of the crew. She may even be hoisted up to the crow’s nest in her wheelchair, but that doesn’t worry her.

“I am terrified of heights, but you’ve got to take these opportunities,” says the girl who was seriously injured in a road traffic accident on 5 August 2015 at the age of 21 and who is now inspiring others with her story of recovery and resilience.

There was still more challenge to come. Complaining of her head hurting six months after the accident, a scan showed that spinal fluid had leaked into her brain

Four years on from that day she tells her story to help others, and in aid of the two hospitals where she was “put back together” as she calls it – the Mater in Dublin and the National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH) in Dun Laoghaire.

Gemma’s list of injuries is long. Put into an induced coma for six weeks, surgeons worked steadfastly to repair the damage – a severed spine that means she has metal rods either side of her spine now, a ruptured bowel, one kidney that couldn’t be saved and a broken cheekbone. It didn’t stop there. Her right leg had to be amputated due to artery damage and the toes on her left foot also had to be removed. There was still more challenge to come. Complaining of her head hurting six months after the accident, a scan showed that spinal fluid had leaked into her brain. Surgery followed immediately.

He told me that there were seven surgeons standing round me trying to decide was it worth their while doing anything as my injuries were so bad

All in all, Gemma had 14 operations in the 16 months she was in hospital. That period included seven months in the NRH learning how to adapt to life in a wheelchair.

She relates what one doctor told her since.

“He told me that there were seven surgeons standing round me trying to decide was it worth their while doing anything as my injuries were so bad,” she says. “It’s shocking to think that. It makes me even more thankful for being alive and doing so well.”

While life now has many challenges including needing a wheelchair, an ileostomy bag and catheter, Gemma focuses on the positive and celebrates the fact that she can be as independent as she is.

“One surgeon that I see constantly for check-ups is amazed to see how I am doing. When I tell him I can change my own stoma bag and can get into the wheelchair myself he is delighted as there was so little hope for me at all in the early days. I had setbacks too so they can’t get over how well I came out of it all.”

Gemma is philosophical about the accident that she has no recollection of. “I always say, ‘For whatever messed up reason, this happened, it was meant to happen’.”

For the 16 months Gemma’s mother stayed with her in the hospital and her Dad, Robert, travelled up and down to the farm.

Take nothing for granted

She admits that acceptance of her situation took time.

“Getting to that point was a mixture of everything – faith and time and understanding. In times of trauma, you need to believe in something, but also you have to grieve and that takes time. You have to understand the real extent of your injuries, also, before you can start to even process it all.”

Gemma says that she had no awareness of disability before her accident.

“I never had contact with wheelchairs before – never pushed one, never sat into one, was never up close to one.”

Now she prefers the one she can push along herself, with its colourful wheels, to an electric one.

I don’t want to know anything about the accident because you can’t change it

“I felt so unindependent when I tried one,” she says.

Gemma and her mother had been travelling back from Naas Hospital in August 2015 where she had had an eye condition treated when the collision occurred.

“I don’t want to know anything about the accident because you can’t change it,” she says.

But isn’t talking about what happened difficult for her?

“No, I’m used to it, and I like talking to Transition Year students about it, for example. I tell them not to take anything for granted, that you might make big plans but that challenging things can happen in life but that good can come out of them. And that friendship is so important. My friends I’ve had since school have been wonderful and I’ll always be thankful for that.”

Gemma now attends a gym in Athy once a week where she swims and lifts weights to build up arm strength.

She is looking forward to Christmas 2019 and because of her cookery skills (she was training to be a pastry chef in Mount Wolseley Hotel before her accident) she will be in charge of making the dessert on Christmas Day for the family and friends gathering of 10 people.

“It will be a Terry’s Chocolate Orange cheesecake,” she says. “It will be my contribution to dinner.”

Gemma spent one Christmas Day in hospital – not a great experience – but had the joy of getting home before Christmas 2016.

In hospital, everything is on level ground and there is someone close all the time, but when you’re home there’s no button to press. It was scary in ways

“Getting home was so nice! I could have a lie-in!”

While she was a bit apprehensive moving from a hospital setting to a home once again her courage grew over time.

“In hospital, everything is on level ground and there is someone close all the time, but when you’re home there’s no button to press. It was scary in ways but I knew it (hospital) wasn’t normal life. The good thing about the Rehab was that when the adjustments were made to the house I used to come home for weekends so the transition was gradual. It’s a case of building up your confidence over time.”

She was glad to get home to her mother’s cooking too.

“Hospital food isn’t the best and it’s funny the things you long for – lamb chops and cheese toasties and homemade soups and, of course, having a sweet tooth and being a chef I was always yearning for interesting desserts so getting home was good!”

She missed the farm also when she was away, she says.

“Lambing was always my favourite time of year. In ways I feel so helpless now but I still try to help when I can, like with bottle feeding or when moving sheep I’ll be the one stopping the gaps.”

What Gemma thinks of our health service

Based on her experience since her accident is she happy with the Irish health service?

“You have to fight for everything,” she says immediately. “To get a wheelchair upgrade, to get your medical card renewed, for physiotherapy, for plastic gloves...

It’s ridiculous the fighting you have to go through. When you have things like an ileostomy bag your situation is not going to change

“My prescription costs about €1000 euro each month so the medical card is vital. Spinal Injuries Ireland, an organisation that I’m now linked in with and with whom I’ll be travelling on the Tall Ships, are campaigning for those with serious spinal injury to automatically get the medical card because it is an illness for life. It’s like the HSE are trying to say it’s not an illness for life. It’s ridiculous the fighting you have to go through. When you have things like an ileostomy bag your situation is not going to change.”

Gemma enjoyed pointing out a few things to Minister for Health Simon Harris when he visited her local clinic, she adds.

The first one was that the gradient of the slope at the building was too steep.

“That’s a new build. Why don’t planners and builders have people in wheelchairs and occupational therapists checking out that everything is right? It’s nonsensical.”

The second was about having an automatically opening door.

“I could get to the door but would have to wait for my mother to open it for me. There is a buzzer on it now that I can press. I’m always delighted when I see it,” she says.

Her opinions about what’s needed for those with disability extends to the new NRH that isn’t open yet.

“The Minister seemed a bit taken aback when I told him that all single cubicles in the new National Rehabilitation Hospital wouldn’t be a good idea. I told him that when you are recovering from something like this you need people around you, someone to talk to. It’s not good for you to be on your own.”

I hated the infection control nurse. She didn’t want anything on my locker whereas I needed everything at hand’s reach

He pointed out that the single cubicles were for infection control reasons.

“I said ‘don’t get me started on that!” she said. “I hated the infection control nurse. She didn’t want anything on my locker whereas I needed everything at hand’s reach, otherwise I would be pressing the bell all the time to ask someone to hand me my toothbrush or whatever. It takes away your independence.”

On the need for wards rather than single cubicles she recalls something she said to a fellow patient in the NRH.

“He hadn’t accepted what had happened to him. I had a lot time to accept it and I said ‘Look, if you are paralysed, you’re paralysed. You can’t change it, you just have to learn to live with it’. It was better him hearing it from me – someone who is living it and breathing it – than from somebody who isn’t. That’s why you need to be around people in hospital, not isolated in single rooms.”

Working as crew we will have to do a different job every four hours. Being a chef they will probably want to keep me in the galley but I want to try everything

In the future Gemma hopes to be able to drive again but in the meantime she has her Tall Ships trip to look forward to.

“I’m very excited about it. I’m hoping for a new lighter weight wheelchair before then. Working as crew we will have to do a different job every four hours. Being a chef they will probably want to keep me in the galley but I want to try everything!”

Gemma is an ambassador for the Mater Foundation which is fund-raising to raise €140,000 for two life-support machines.

The words “Gemma Is Amazing” are written on a sheep shed wall on the Willis farm in Tullow, Co Carlow. The statement, in pink fluorescent paint, is the first thing you see when you open the door. The words bear testimony to the wonderful recovery from a very serious car accident of Gemma Willis, now 25.

Gemma Willis.

Focusing on the positive

Gemma Willis has big plans for 2020. She will be sailing on a Tall Ship from Cadiz to Lisbon as part of the Parade of Sails race and she will be part of the crew. She may even be hoisted up to the crow’s nest in her wheelchair, but that doesn’t worry her.

“I am terrified of heights, but you’ve got to take these opportunities,” says the girl who was seriously injured in a road traffic accident on 5 August 2015 at the age of 21 and who is now inspiring others with her story of recovery and resilience.

There was still more challenge to come. Complaining of her head hurting six months after the accident, a scan showed that spinal fluid had leaked into her brain

Four years on from that day she tells her story to help others, and in aid of the two hospitals where she was “put back together” as she calls it – the Mater in Dublin and the National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH) in Dun Laoghaire.

Gemma’s list of injuries is long. Put into an induced coma for six weeks, surgeons worked steadfastly to repair the damage – a severed spine that means she has metal rods either side of her spine now, a ruptured bowel, one kidney that couldn’t be saved and a broken cheekbone. It didn’t stop there. Her right leg had to be amputated due to artery damage and the toes on her left foot also had to be removed. There was still more challenge to come. Complaining of her head hurting six months after the accident, a scan showed that spinal fluid had leaked into her brain. Surgery followed immediately.

He told me that there were seven surgeons standing round me trying to decide was it worth their while doing anything as my injuries were so bad

All in all, Gemma had 14 operations in the 16 months she was in hospital. That period included seven months in the NRH learning how to adapt to life in a wheelchair.

She relates what one doctor told her since.

“He told me that there were seven surgeons standing round me trying to decide was it worth their while doing anything as my injuries were so bad,” she says. “It’s shocking to think that. It makes me even more thankful for being alive and doing so well.”

While life now has many challenges including needing a wheelchair, an ileostomy bag and catheter, Gemma focuses on the positive and celebrates the fact that she can be as independent as she is.

“One surgeon that I see constantly for check-ups is amazed to see how I am doing. When I tell him I can change my own stoma bag and can get into the wheelchair myself he is delighted as there was so little hope for me at all in the early days. I had setbacks too so they can’t get over how well I came out of it all.”

Gemma is philosophical about the accident that she has no recollection of. “I always say, ‘For whatever messed up reason, this happened, it was meant to happen’.”

For the 16 months Gemma’s mother stayed with her in the hospital and her Dad, Robert, travelled up and down to the farm.

Take nothing for granted

She admits that acceptance of her situation took time.

“Getting to that point was a mixture of everything – faith and time and understanding. In times of trauma, you need to believe in something, but also you have to grieve and that takes time. You have to understand the real extent of your injuries, also, before you can start to even process it all.”

Gemma says that she had no awareness of disability before her accident.

“I never had contact with wheelchairs before – never pushed one, never sat into one, was never up close to one.”

Now she prefers the one she can push along herself, with its colourful wheels, to an electric one.

I don’t want to know anything about the accident because you can’t change it

“I felt so unindependent when I tried one,” she says.

Gemma and her mother had been travelling back from Naas Hospital in August 2015 where she had had an eye condition treated when the collision occurred.

“I don’t want to know anything about the accident because you can’t change it,” she says.

But isn’t talking about what happened difficult for her?

“No, I’m used to it, and I like talking to Transition Year students about it, for example. I tell them not to take anything for granted, that you might make big plans but that challenging things can happen in life but that good can come out of them. And that friendship is so important. My friends I’ve had since school have been wonderful and I’ll always be thankful for that.”

Gemma now attends a gym in Athy once a week where she swims and lifts weights to build up arm strength.

She is looking forward to Christmas 2019 and because of her cookery skills (she was training to be a pastry chef in Mount Wolseley Hotel before her accident) she will be in charge of making the dessert on Christmas Day for the family and friends gathering of 10 people.

“It will be a Terry’s Chocolate Orange cheesecake,” she says. “It will be my contribution to dinner.”

Gemma spent one Christmas Day in hospital – not a great experience – but had the joy of getting home before Christmas 2016.

In hospital, everything is on level ground and there is someone close all the time, but when you’re home there’s no button to press. It was scary in ways

“Getting home was so nice! I could have a lie-in!”

While she was a bit apprehensive moving from a hospital setting to a home once again her courage grew over time.

“In hospital, everything is on level ground and there is someone close all the time, but when you’re home there’s no button to press. It was scary in ways but I knew it (hospital) wasn’t normal life. The good thing about the Rehab was that when the adjustments were made to the house I used to come home for weekends so the transition was gradual. It’s a case of building up your confidence over time.”

She was glad to get home to her mother’s cooking too.

“Hospital food isn’t the best and it’s funny the things you long for – lamb chops and cheese toasties and homemade soups and, of course, having a sweet tooth and being a chef I was always yearning for interesting desserts so getting home was good!”

She missed the farm also when she was away, she says.

“Lambing was always my favourite time of year. In ways I feel so helpless now but I still try to help when I can, like with bottle feeding or when moving sheep I’ll be the one stopping the gaps.”

What Gemma thinks of our health service

Based on her experience since her accident is she happy with the Irish health service?

“You have to fight for everything,” she says immediately. “To get a wheelchair upgrade, to get your medical card renewed, for physiotherapy, for plastic gloves...

It’s ridiculous the fighting you have to go through. When you have things like an ileostomy bag your situation is not going to change

“My prescription costs about €1000 euro each month so the medical card is vital. Spinal Injuries Ireland, an organisation that I’m now linked in with and with whom I’ll be travelling on the Tall Ships, are campaigning for those with serious spinal injury to automatically get the medical card because it is an illness for life. It’s like the HSE are trying to say it’s not an illness for life. It’s ridiculous the fighting you have to go through. When you have things like an ileostomy bag your situation is not going to change.”

Gemma enjoyed pointing out a few things to Minister for Health Simon Harris when he visited her local clinic, she adds.

The first one was that the gradient of the slope at the building was too steep.

“That’s a new build. Why don’t planners and builders have people in wheelchairs and occupational therapists checking out that everything is right? It’s nonsensical.”

The second was about having an automatically opening door.

“I could get to the door but would have to wait for my mother to open it for me. There is a buzzer on it now that I can press. I’m always delighted when I see it,” she says.

Her opinions about what’s needed for those with disability extends to the new NRH that isn’t open yet.

“The Minister seemed a bit taken aback when I told him that all single cubicles in the new National Rehabilitation Hospital wouldn’t be a good idea. I told him that when you are recovering from something like this you need people around you, someone to talk to. It’s not good for you to be on your own.”

I hated the infection control nurse. She didn’t want anything on my locker whereas I needed everything at hand’s reach

He pointed out that the single cubicles were for infection control reasons.

“I said ‘don’t get me started on that!” she said. “I hated the infection control nurse. She didn’t want anything on my locker whereas I needed everything at hand’s reach, otherwise I would be pressing the bell all the time to ask someone to hand me my toothbrush or whatever. It takes away your independence.”

On the need for wards rather than single cubicles she recalls something she said to a fellow patient in the NRH.

“He hadn’t accepted what had happened to him. I had a lot time to accept it and I said ‘Look, if you are paralysed, you’re paralysed. You can’t change it, you just have to learn to live with it’. It was better him hearing it from me – someone who is living it and breathing it – than from somebody who isn’t. That’s why you need to be around people in hospital, not isolated in single rooms.”

Working as crew we will have to do a different job every four hours. Being a chef they will probably want to keep me in the galley but I want to try everything

In the future Gemma hopes to be able to drive again but in the meantime she has her Tall Ships trip to look forward to.

“I’m very excited about it. I’m hoping for a new lighter weight wheelchair before then. Working as crew we will have to do a different job every four hours. Being a chef they will probably want to keep me in the galley but I want to try everything!”

Gemma is an ambassador for the Mater Foundation which is fund-raising to raise €140,000 for two life-support machines.

SHARING OPTIONS