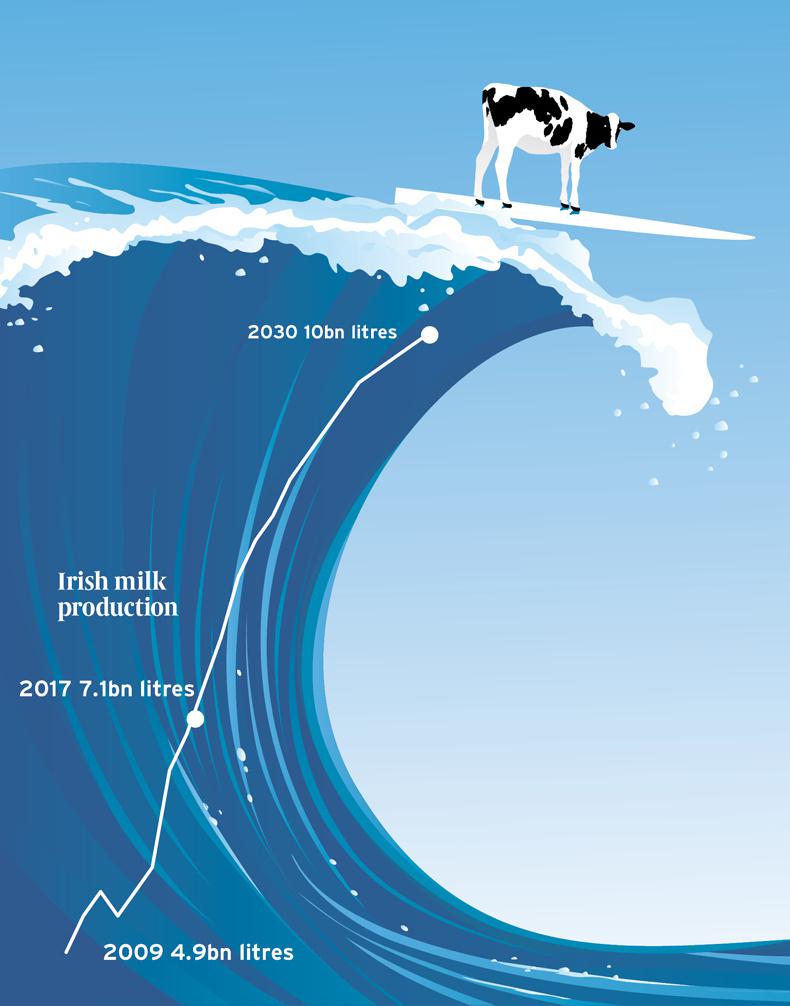

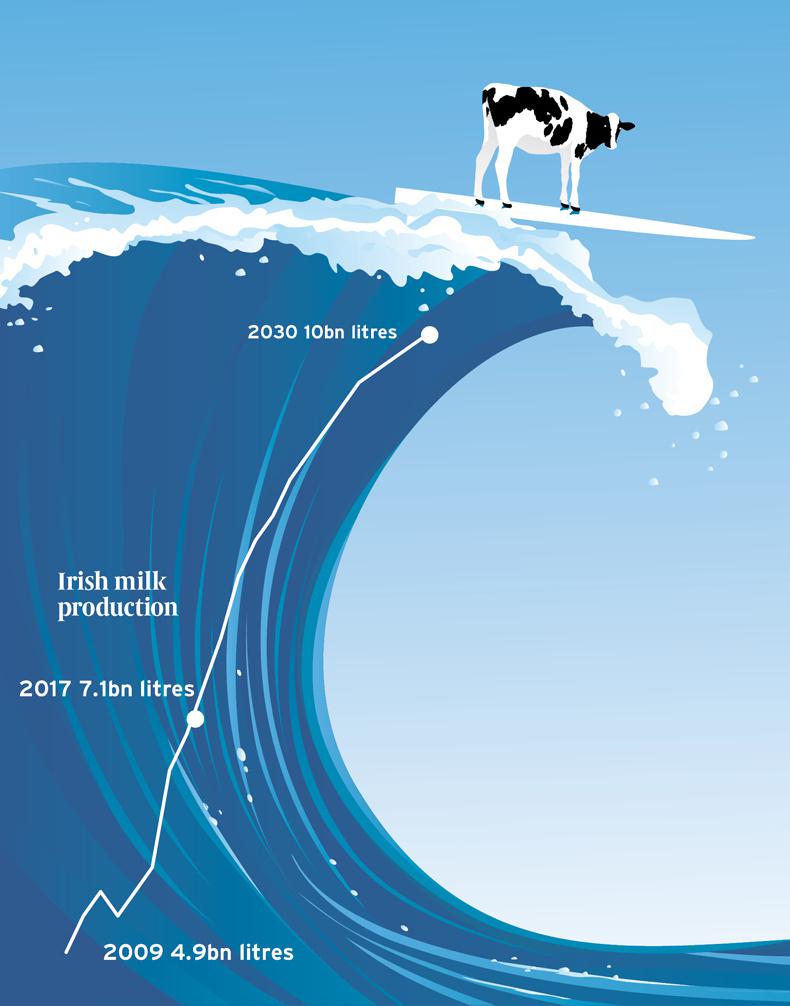

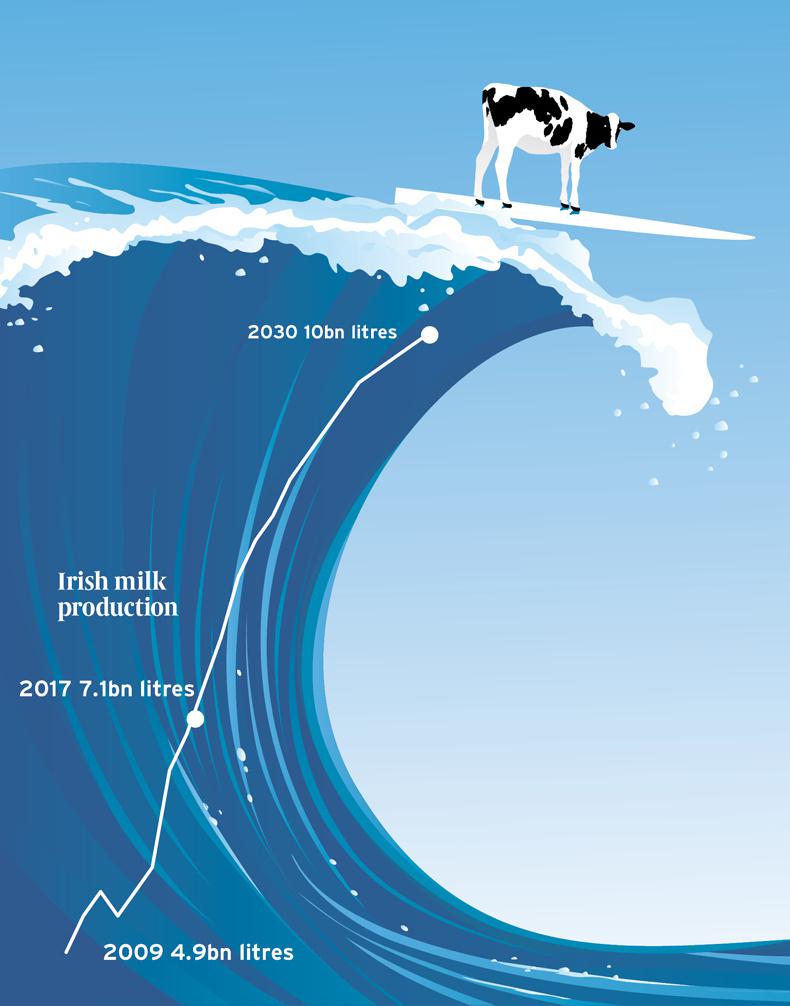

Irish milk production looks set to be up 7% to reach 7.1bn litres this year. Assuming this pace of growth continues next year, Ireland will have hit its Food Harvest 2020 targets of 50% milk output growth two years ahead of schedule. And the growth doesn’t look set to moderate anytime soon. A recent poll by the country’s largest dairy processor, Glanbia Ireland, forecast that its suppliers have the ambition to expand output by a further 30% between 2016 and 2020.

While the Food Harvest 2020 target was set at 7.5bn litres, many dairy co-ops are now talking about the potential for Ireland to produce 10bn litres of milk in the future. Obviously the current pace of growth is unlikely to be sustained, but an annual growth rate of about 3% over the next 13 years would see Ireland producing 10bn litres by 2030.

But could this output be realistically achieved? Today Ireland has 1.4m dairy cows. To produce 10bn litres, the dairy herd would need to expand by 600,000hd to reach 2m cows. In a recent report, Teagasc forecast there will be 1.6m dairy cows in Ireland by 2025. Many have suggested these figures may be conservative. The optimism to continue expansion among dairy farmers is evident. However, the extra milk flowing from the farm gate raises a number of issues for the industry.

Where will the growth come from?

Currently the average density of dairy cows in Ireland is 1 cow/5ha. Cork, with 1 dairy cow/2ha has the highest density, while Leitrim with 1 cow/50ha has the lowest. On this basis, the counties with the largest potential to expand dairy numbers are located mainly in Leinster. Teagasc has also identified Roscommon as a county with significant potential. Outside of increasing cow numbers, the other options for expansion would require the cow to produce more than the current 5,000 litres average per year.

How much investment would be required?

As we have already seen, expansion requires significant investment at both processing and farm level. To date, farmers have invested at least €1bn on farm while €1bn has also been invested in processing capacity to process the extra 2bn litres we have seen to date. This works out at a total investment cost of 70-80c/l. This would suggest a further €2bn combined investment from farmers and processors could be required to reach 10bn litres.

Will environmental limitations be the new quota?

While growth is positive, the Irish dairy industry needs to be aware of its environmental limitations. We have seen how New Zealand and the Netherlands, having pushed the bounds of production, are now coming under environmental pressures. The last thing the country needs is a situation similar to the Netherlands, where after investments have been made, farmers are instructed to cull numbers and reduce stocking rates.

What will Ireland’s future product mix look like?

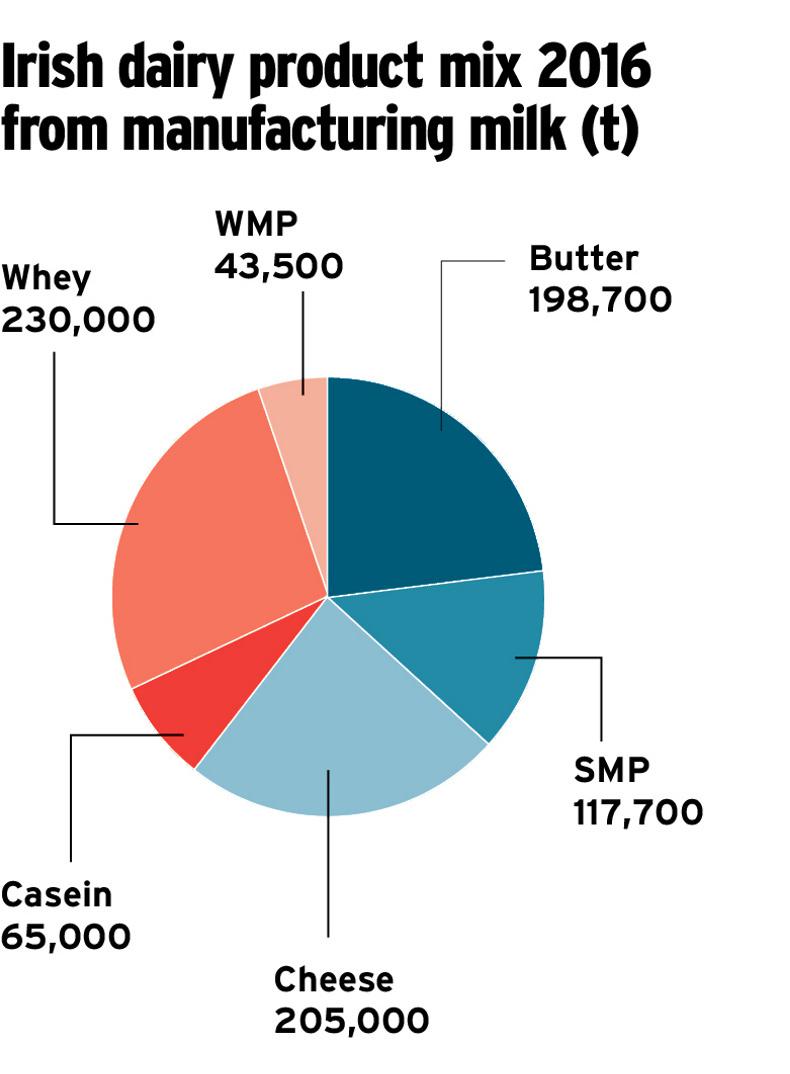

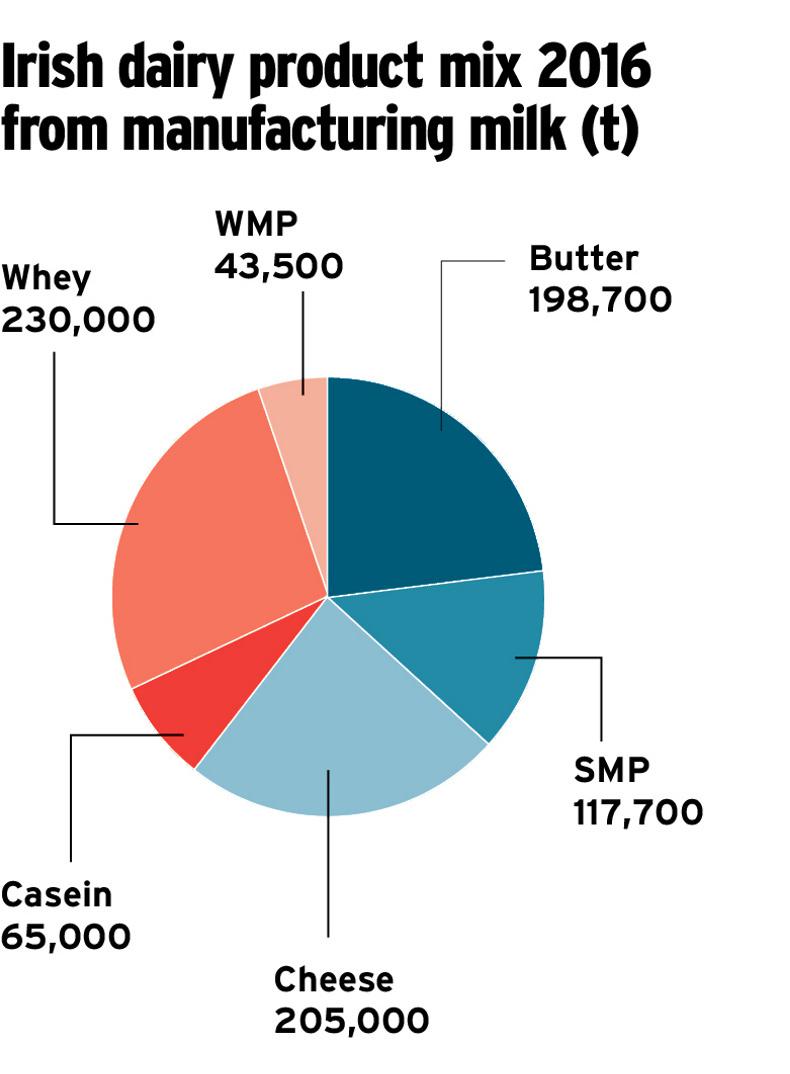

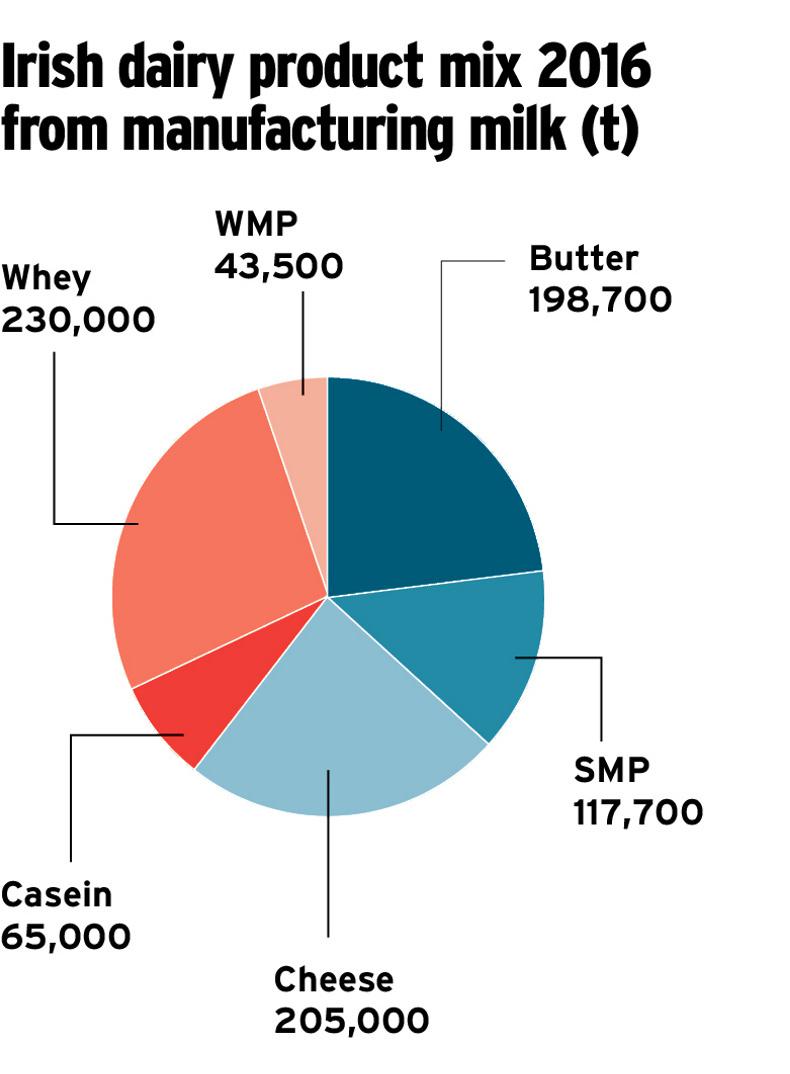

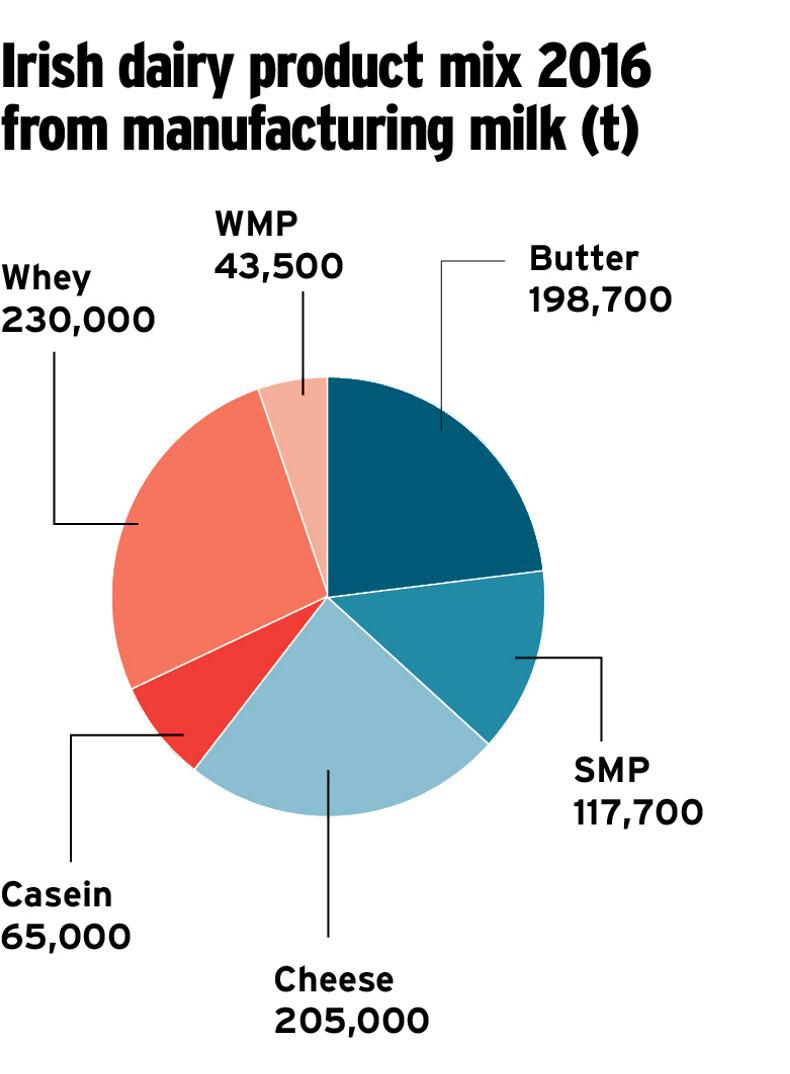

Excluding some 500m litres for liquid milk, Ireland had 6.2bn litres available for manufacturing in 2016. Around two-thirds or 4bn litres was processed into 200,000t of butter, which also yields around 120,000t of skim milk powder. Around half of the butter is sold under the Kerrygold brand.

Cheese production uses just under one-third or almost 2bn litres of Ireland’s manufacturing milk pool, with 200,000t produced last year. We also produces about 65,000t of casein. This cheese and casein production yields some 230,000t of whey, which is processed further into many ingredients including infant formula and sports nutrition. The balance or 5% of manufacturing milk is dried into whole milk powder (WMP).

Where will dairy exports go in the future?

According to the EU’s Milk Marketing Observatory, Ireland exported 170,000t of butter last year. Of this, 80% or 135,000t went to the EU. The UK imported 40,000t, with the largest market, Germany, taking almost 60,000t while the US imported almost 20,000t.

Almost two-thirds (140,000t) of Ireland’s cheese production went to the UK, with some 50,000t exported to markets outside the EU. While our butter and cheese exports are heavily weighted to the UK and EU markets, Irish dairy powder exports are split 50:50 between the EU and international markets.

The EU is a mature market where demand growth for butter and cheese is forecast at a steady 1-2% per year over the next 10 years. International markets have been the largest driver of dairy export growth in recent years, with China now our second largest export market for dairy products in value terms. Therefore, the most obvious market for most of the next 3bn litres is outside the EU.

If this is the case, then it is likely that more milk will be dried into powders destined for Asian markets. Farmers will need to understand this will have a profound impact on our dairy product mix and ultimately on how the milk price is calculated.

Assuming we reach 10bn litres, and additional capacity is installed to dry milk (as happened up to now), the shape of Ireland’s product mix will change dramatically. Assuming 15% EU demand growth for butter and cheese between now and 2030, demand will increase to 235,000t for cheese and 230,000t for butter. This will push more than a quarter of all manufacturing milk into powders. This would see a fivefold increase in powder production from today’s 44,000t to in excess of 300,000t per year.

This would mean Ireland would need to grow its market share of the world powder market from 2% today to 10% by 2030.

The impact of this could be threefold. Firstly, it puts us firmly on the playing field with giants such as Fonterra, which accounts for 50% of global WMP exports. Secondly, selling commodity milk powder into emerging markets makes it very difficult to differentiate your product.

Thirdly, and most important for farmers, there is the impact of exporting dairy powders to global markets has on milk prices. Today, the farmgate milk price is predominantly influenced by butter and cheese markets. In the future, increased powder exports will further expose the milk price to the volatility of global powder markets.

Ireland’s dairy industry has decisions to make

If you asked an Irish dairy farmer what their competitive advantage is, they would tell you it is producing milk from grass. At processing level, it could be argued our competitive advantage is our butter industry. Not only does making butter use two-thirds of our milk, Ireland’s butter through the Kerrygold brand commands a premium in every market in which it is sold.

While Ireland accounts for as little as 4% of the EU’s total milk pool, it accounts for 10% of all butter production in Europe. We are now the third largest producer of butter in Europe, behind Germany and France. Ireland has also become the EU’s largest butter exporter to international markets, overtaking France for the first time last year. Meanwhile, Kerrygold is the number one imported butter into the US.

Ireland’s dairy industry needs to be clear on its strategy on where it will find a home for more milk. We know investment will be required, but how can the industry invest in capacity while moving up the value chain at the same time? Otherwise we will be small players competing with giants.

The easiest option is to dry milk into powder so it can be cost-effectively moved around the world.

However, the main problem with selling milk powders is that it’s very hard to differentiate yourself when these markets can have just a single specification for milk powder and there are 10 suppliers trying to capture that market.

But if we look at milk as a source of protein, does drying really maximise its nutritional value? Is there a more functional approach we can take to processing milk in the future?

Butter is a rich-world product. As an island, sitting between continental Europe and North America, we are located within reach of the wealthiest consumers in the world. We know these consumers want nutrient-dense quality food. Irish milk has it in abundance.

What is clear is that there is a clear decision facing the industry. Do we invest in logistics or do we invest in science? Investing in logistics means building drying capacity that allows us to move dairy nutrients as cheaply as possible around the world.

However, if we invest in science it will allow us to extract the maximum nutrient value from milk that not only adds value to customers but also to farmers.

Read more

Dairy Day: industry needs strategy before further expansion

Dairy Day: Kerry and Arrabawn plan up to €80m investment

Full coverage: Dairy Day 2017

Irish milk production looks set to be up 7% to reach 7.1bn litres this year. Assuming this pace of growth continues next year, Ireland will have hit its Food Harvest 2020 targets of 50% milk output growth two years ahead of schedule. And the growth doesn’t look set to moderate anytime soon. A recent poll by the country’s largest dairy processor, Glanbia Ireland, forecast that its suppliers have the ambition to expand output by a further 30% between 2016 and 2020.

While the Food Harvest 2020 target was set at 7.5bn litres, many dairy co-ops are now talking about the potential for Ireland to produce 10bn litres of milk in the future. Obviously the current pace of growth is unlikely to be sustained, but an annual growth rate of about 3% over the next 13 years would see Ireland producing 10bn litres by 2030.

But could this output be realistically achieved? Today Ireland has 1.4m dairy cows. To produce 10bn litres, the dairy herd would need to expand by 600,000hd to reach 2m cows. In a recent report, Teagasc forecast there will be 1.6m dairy cows in Ireland by 2025. Many have suggested these figures may be conservative. The optimism to continue expansion among dairy farmers is evident. However, the extra milk flowing from the farm gate raises a number of issues for the industry.

Where will the growth come from?

Currently the average density of dairy cows in Ireland is 1 cow/5ha. Cork, with 1 dairy cow/2ha has the highest density, while Leitrim with 1 cow/50ha has the lowest. On this basis, the counties with the largest potential to expand dairy numbers are located mainly in Leinster. Teagasc has also identified Roscommon as a county with significant potential. Outside of increasing cow numbers, the other options for expansion would require the cow to produce more than the current 5,000 litres average per year.

How much investment would be required?

As we have already seen, expansion requires significant investment at both processing and farm level. To date, farmers have invested at least €1bn on farm while €1bn has also been invested in processing capacity to process the extra 2bn litres we have seen to date. This works out at a total investment cost of 70-80c/l. This would suggest a further €2bn combined investment from farmers and processors could be required to reach 10bn litres.

Will environmental limitations be the new quota?

While growth is positive, the Irish dairy industry needs to be aware of its environmental limitations. We have seen how New Zealand and the Netherlands, having pushed the bounds of production, are now coming under environmental pressures. The last thing the country needs is a situation similar to the Netherlands, where after investments have been made, farmers are instructed to cull numbers and reduce stocking rates.

What will Ireland’s future product mix look like?

Excluding some 500m litres for liquid milk, Ireland had 6.2bn litres available for manufacturing in 2016. Around two-thirds or 4bn litres was processed into 200,000t of butter, which also yields around 120,000t of skim milk powder. Around half of the butter is sold under the Kerrygold brand.

Cheese production uses just under one-third or almost 2bn litres of Ireland’s manufacturing milk pool, with 200,000t produced last year. We also produces about 65,000t of casein. This cheese and casein production yields some 230,000t of whey, which is processed further into many ingredients including infant formula and sports nutrition. The balance or 5% of manufacturing milk is dried into whole milk powder (WMP).

Where will dairy exports go in the future?

According to the EU’s Milk Marketing Observatory, Ireland exported 170,000t of butter last year. Of this, 80% or 135,000t went to the EU. The UK imported 40,000t, with the largest market, Germany, taking almost 60,000t while the US imported almost 20,000t.

Almost two-thirds (140,000t) of Ireland’s cheese production went to the UK, with some 50,000t exported to markets outside the EU. While our butter and cheese exports are heavily weighted to the UK and EU markets, Irish dairy powder exports are split 50:50 between the EU and international markets.

The EU is a mature market where demand growth for butter and cheese is forecast at a steady 1-2% per year over the next 10 years. International markets have been the largest driver of dairy export growth in recent years, with China now our second largest export market for dairy products in value terms. Therefore, the most obvious market for most of the next 3bn litres is outside the EU.

If this is the case, then it is likely that more milk will be dried into powders destined for Asian markets. Farmers will need to understand this will have a profound impact on our dairy product mix and ultimately on how the milk price is calculated.

Assuming we reach 10bn litres, and additional capacity is installed to dry milk (as happened up to now), the shape of Ireland’s product mix will change dramatically. Assuming 15% EU demand growth for butter and cheese between now and 2030, demand will increase to 235,000t for cheese and 230,000t for butter. This will push more than a quarter of all manufacturing milk into powders. This would see a fivefold increase in powder production from today’s 44,000t to in excess of 300,000t per year.

This would mean Ireland would need to grow its market share of the world powder market from 2% today to 10% by 2030.

The impact of this could be threefold. Firstly, it puts us firmly on the playing field with giants such as Fonterra, which accounts for 50% of global WMP exports. Secondly, selling commodity milk powder into emerging markets makes it very difficult to differentiate your product.

Thirdly, and most important for farmers, there is the impact of exporting dairy powders to global markets has on milk prices. Today, the farmgate milk price is predominantly influenced by butter and cheese markets. In the future, increased powder exports will further expose the milk price to the volatility of global powder markets.

Ireland’s dairy industry has decisions to make

If you asked an Irish dairy farmer what their competitive advantage is, they would tell you it is producing milk from grass. At processing level, it could be argued our competitive advantage is our butter industry. Not only does making butter use two-thirds of our milk, Ireland’s butter through the Kerrygold brand commands a premium in every market in which it is sold.

While Ireland accounts for as little as 4% of the EU’s total milk pool, it accounts for 10% of all butter production in Europe. We are now the third largest producer of butter in Europe, behind Germany and France. Ireland has also become the EU’s largest butter exporter to international markets, overtaking France for the first time last year. Meanwhile, Kerrygold is the number one imported butter into the US.

Ireland’s dairy industry needs to be clear on its strategy on where it will find a home for more milk. We know investment will be required, but how can the industry invest in capacity while moving up the value chain at the same time? Otherwise we will be small players competing with giants.

The easiest option is to dry milk into powder so it can be cost-effectively moved around the world.

However, the main problem with selling milk powders is that it’s very hard to differentiate yourself when these markets can have just a single specification for milk powder and there are 10 suppliers trying to capture that market.

But if we look at milk as a source of protein, does drying really maximise its nutritional value? Is there a more functional approach we can take to processing milk in the future?

Butter is a rich-world product. As an island, sitting between continental Europe and North America, we are located within reach of the wealthiest consumers in the world. We know these consumers want nutrient-dense quality food. Irish milk has it in abundance.

What is clear is that there is a clear decision facing the industry. Do we invest in logistics or do we invest in science? Investing in logistics means building drying capacity that allows us to move dairy nutrients as cheaply as possible around the world.

However, if we invest in science it will allow us to extract the maximum nutrient value from milk that not only adds value to customers but also to farmers.

Read more

Dairy Day: industry needs strategy before further expansion

Dairy Day: Kerry and Arrabawn plan up to €80m investment

Full coverage: Dairy Day 2017

SHARING OPTIONS