The performance of Ireland’s afforestation programme including meeting the 30% target for planting broadleaves has come under scrutiny in recent years. This is due to the drop in new planting since 2007 and the decrease in average broadleaf planting since 2012. The drop in broadleaf planting coincided with ash dieback, which wiped out the annual ash afforestation programme, then at 760ha or 30% of the overall broadleaf planting programme.

The reasons for the reduction in the coniferous afforestation programme are more complex. While income generation in annual premium payments and log prices is high and climate change benefits should be creating a positive environment for afforestation, the programme continues to falter. The reasons include land availability, or non-availability, planning restrictions, competing land use schemes and the replanting obligation. Also, factors such as ash dieback and windblow highlight the risk factors associated with investment in forestry.

The debate on increasing species diversity, especially broadleaf diversity, often takes place in the absence of the key stakeholders charged with the task of achieving a viable national afforestation programme, including a challenging native species mix. These are the forest owners or potential forest owners. Other stakeholders quite rightly have an important contribution to make in the forestry debate but the key is to find out why landowners – now mainly farmers – plant and what kind of forests they wish to establish and manage into the future. The recent debate among non-forest owner stakeholders gives the impression that forest owners in Ireland only wish to establish highly commercial forests in the shortest possible rotations.

Income generation is without doubt the main objective of most growers, but it’s not the only aim. For example in 2011, the year before ash dieback, the annual planting programme comprised Sitka spruce (48%), diverse conifers (15%) and broadleaves (37%). This trend would have been maintained if ash dieback had not decimated the broadleaf planting programme the following year as foresters and researchers still struggle to find an alternative native species.

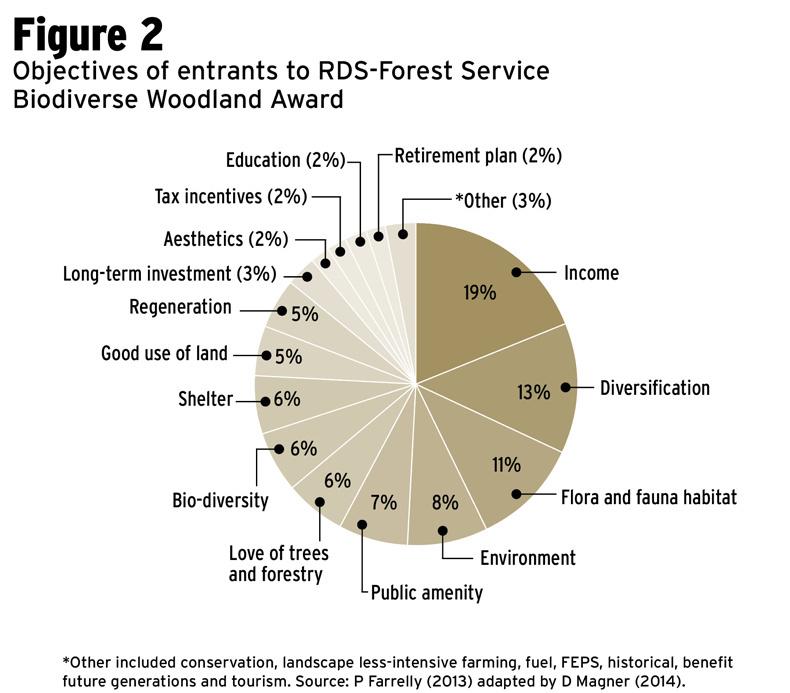

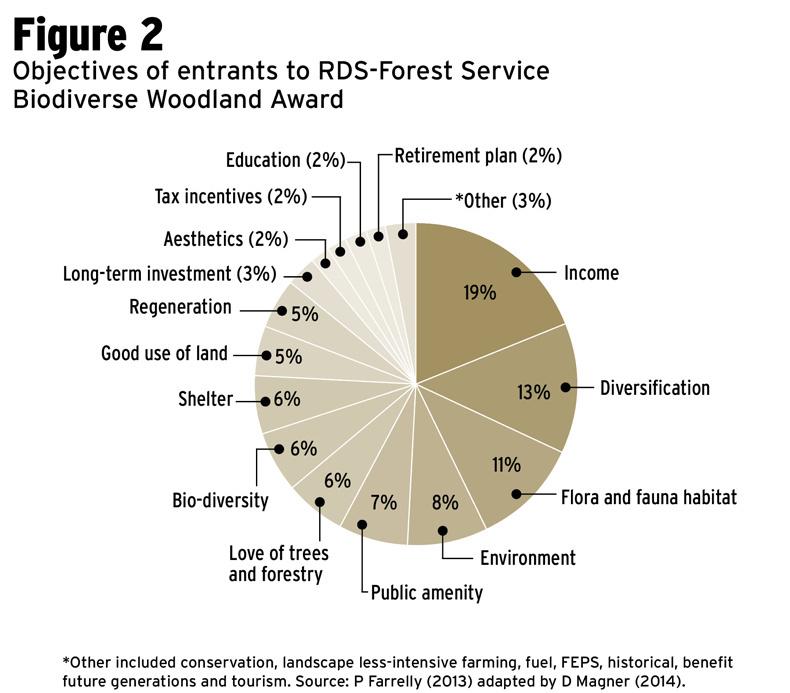

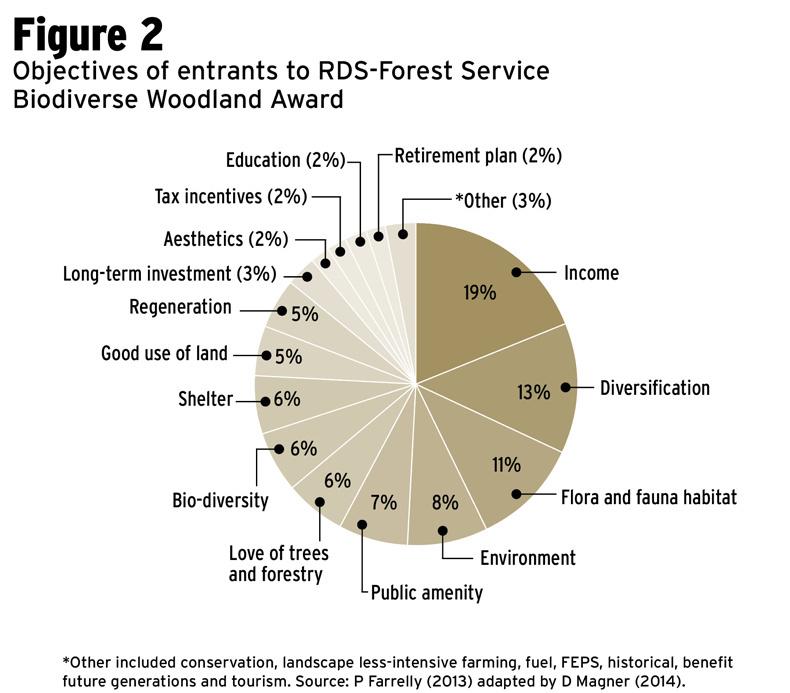

Forest owners’ approach to forestry as a multipurpose land use is obvious to those who take the time to ask growers what they expect from their forests. For example, a study carried out by the RDS in 2013 demonstrated that forest owners who entered the RDS-Forest Service Forestry Awards rated income generation highly but also had a diverse range of other objectives in mind.

This study carried out by Paul Farrelly on behalf of the RDS is worth revisiting. It listed 26 objectives rated on a multiple-point system in a detailed questionnaire sent to all forest owners who entered the then Farm Forestry Award and the Biodiverse Woodland Award.

The main preferences of Farm Forestry Award entrants (Figure 1) were income generation (21%), diversification (20%), environment (8%), good use of land (8%), love of trees and forestry (8%) and habitat enhancement (7%). Objectives such as shelter, long-term investment, tax incentives and public amenity were rated at 4% and lower.

The main preferences of Biodiverse Woodland Award entrants (Figure 2) were more evenly spread. Income generation (19%) and diversification (13%) were lower for Biodiverse Award entrants while habitat enhancement (11%), environment (8%) and public amenity (7%) were rated higher.

The study was confined to award entrants and may not reflect the views of all private forest owners but it does reflect a divergence of objectives among award entrants, all of whom place a strong emphasis on growing quality forests.

These, along with producers groups, forest owners, foresters and forestry companies are the key stakeholders because they make the land available and then manage the resource. Multifunctional forestry has multipurpose objectives, but the overriding aim is to grow quality, regardless of species and land type. Growing quality ensures that a myriad of wood and non-wood benefits flow.

Listening to the people who work the land and create the resource is an obvious prerequisite to achieving a sustainable forestry programme that will, in the words of Seamus Heaney “keep the green lungs of the country breathing and the dark roots drinking”.

Premium and grant rates in revised Native Woodland Scheme

In a recent article on changes to the Native Woodland Scheme (NWS), we omitted grant and premium rates due to pressure of space. This Forest Service scheme has been welcomed by forestry stakeholders as it applies to both native woodland establishment and conservation projects.

The NWS Framework includes a new Scenario 5 which is designed to encourage the establishment of native woodlands in sites classified as “Highly Modified Peat & Peaty Podzols/Pioneer Birch Woodland”.

Scenario 5 provides opportunities to reconnect with the upland pine and birch forests in a scheme similar to the recolonisation and recreation of the Caledonian Forest in Scotland.

It will support the planting of modified and improved, infertile upland acid brown earths and peaty podzols to include moderately acid, drained improved peat sites and peaty gleys in both upland (blanket bog) and lowland (raised bog) habitats.

Foresters and landowners – mainly farmers – believe the introduction of Scenario 5 could be a game changer in helping achieve the 30% target for broadleaves and native species.

It has the potential to provide ecological and aesthetic benefits while timber production will also be achieved but over much longer rotations than conventional commercial forestry.

The establishment of native woodlands requires intensive management and maintenance which is reflected in the grant and tax-free premium rates outlined in Table 1.

The performance of Ireland’s afforestation programme including meeting the 30% target for planting broadleaves has come under scrutiny in recent years. This is due to the drop in new planting since 2007 and the decrease in average broadleaf planting since 2012. The drop in broadleaf planting coincided with ash dieback, which wiped out the annual ash afforestation programme, then at 760ha or 30% of the overall broadleaf planting programme.

The reasons for the reduction in the coniferous afforestation programme are more complex. While income generation in annual premium payments and log prices is high and climate change benefits should be creating a positive environment for afforestation, the programme continues to falter. The reasons include land availability, or non-availability, planning restrictions, competing land use schemes and the replanting obligation. Also, factors such as ash dieback and windblow highlight the risk factors associated with investment in forestry.

The debate on increasing species diversity, especially broadleaf diversity, often takes place in the absence of the key stakeholders charged with the task of achieving a viable national afforestation programme, including a challenging native species mix. These are the forest owners or potential forest owners. Other stakeholders quite rightly have an important contribution to make in the forestry debate but the key is to find out why landowners – now mainly farmers – plant and what kind of forests they wish to establish and manage into the future. The recent debate among non-forest owner stakeholders gives the impression that forest owners in Ireland only wish to establish highly commercial forests in the shortest possible rotations.

Income generation is without doubt the main objective of most growers, but it’s not the only aim. For example in 2011, the year before ash dieback, the annual planting programme comprised Sitka spruce (48%), diverse conifers (15%) and broadleaves (37%). This trend would have been maintained if ash dieback had not decimated the broadleaf planting programme the following year as foresters and researchers still struggle to find an alternative native species.

Forest owners’ approach to forestry as a multipurpose land use is obvious to those who take the time to ask growers what they expect from their forests. For example, a study carried out by the RDS in 2013 demonstrated that forest owners who entered the RDS-Forest Service Forestry Awards rated income generation highly but also had a diverse range of other objectives in mind.

This study carried out by Paul Farrelly on behalf of the RDS is worth revisiting. It listed 26 objectives rated on a multiple-point system in a detailed questionnaire sent to all forest owners who entered the then Farm Forestry Award and the Biodiverse Woodland Award.

The main preferences of Farm Forestry Award entrants (Figure 1) were income generation (21%), diversification (20%), environment (8%), good use of land (8%), love of trees and forestry (8%) and habitat enhancement (7%). Objectives such as shelter, long-term investment, tax incentives and public amenity were rated at 4% and lower.

The main preferences of Biodiverse Woodland Award entrants (Figure 2) were more evenly spread. Income generation (19%) and diversification (13%) were lower for Biodiverse Award entrants while habitat enhancement (11%), environment (8%) and public amenity (7%) were rated higher.

The study was confined to award entrants and may not reflect the views of all private forest owners but it does reflect a divergence of objectives among award entrants, all of whom place a strong emphasis on growing quality forests.

These, along with producers groups, forest owners, foresters and forestry companies are the key stakeholders because they make the land available and then manage the resource. Multifunctional forestry has multipurpose objectives, but the overriding aim is to grow quality, regardless of species and land type. Growing quality ensures that a myriad of wood and non-wood benefits flow.

Listening to the people who work the land and create the resource is an obvious prerequisite to achieving a sustainable forestry programme that will, in the words of Seamus Heaney “keep the green lungs of the country breathing and the dark roots drinking”.

Premium and grant rates in revised Native Woodland Scheme

In a recent article on changes to the Native Woodland Scheme (NWS), we omitted grant and premium rates due to pressure of space. This Forest Service scheme has been welcomed by forestry stakeholders as it applies to both native woodland establishment and conservation projects.

The NWS Framework includes a new Scenario 5 which is designed to encourage the establishment of native woodlands in sites classified as “Highly Modified Peat & Peaty Podzols/Pioneer Birch Woodland”.

Scenario 5 provides opportunities to reconnect with the upland pine and birch forests in a scheme similar to the recolonisation and recreation of the Caledonian Forest in Scotland.

It will support the planting of modified and improved, infertile upland acid brown earths and peaty podzols to include moderately acid, drained improved peat sites and peaty gleys in both upland (blanket bog) and lowland (raised bog) habitats.

Foresters and landowners – mainly farmers – believe the introduction of Scenario 5 could be a game changer in helping achieve the 30% target for broadleaves and native species.

It has the potential to provide ecological and aesthetic benefits while timber production will also be achieved but over much longer rotations than conventional commercial forestry.

The establishment of native woodlands requires intensive management and maintenance which is reflected in the grant and tax-free premium rates outlined in Table 1.

SHARING OPTIONS