The news came about 7.30pm. It was the summer holidays so our son, Ronan, had gone off for the day with Brendan, and I was at home with Grace, who would turn three the following month.

“I was on the laptop booking our flights for our family holiday at Christmas. I had put in our four names and was literally on the second page booking in our baggage when a car drove into the yard. It was Brendan’s brother and his brother-in-law. I was saying: ‘Come in, have a cup of tea’; but he told me there had been an accident…

“Brendan and I first met in a pub in Nenagh called The Railway Bar. I used to play traditional music at a session there every Saturday night and he was a customer. Brendan had a great sense of humour. He enjoyed a good yarn and was able to tell one himself. He looked very like the film actor Chuck Norris, so he was regularly stopped for photographs. He was easy going and would never get flustered about anything. I would be the type of person who would panic about things, but he was always able to bring me down to earth. We balanced each other out that way.

“We were living in a house in Nenagh that had a great big yard suitable for tractors to turn in, which was the main reason this house was bought. But the dream was to eventually live on the farm and we had the plans drawn up. He wanted me to look after this, as he used to say that he would be happy to live in a hen house.

“Another dream of his was to live on one of the Canary Islands for the winter months. We were looking at job prospects over there, but he still planned on coming back to Ireland for the summer months to go at silage and corn. He just couldn’t give it up.

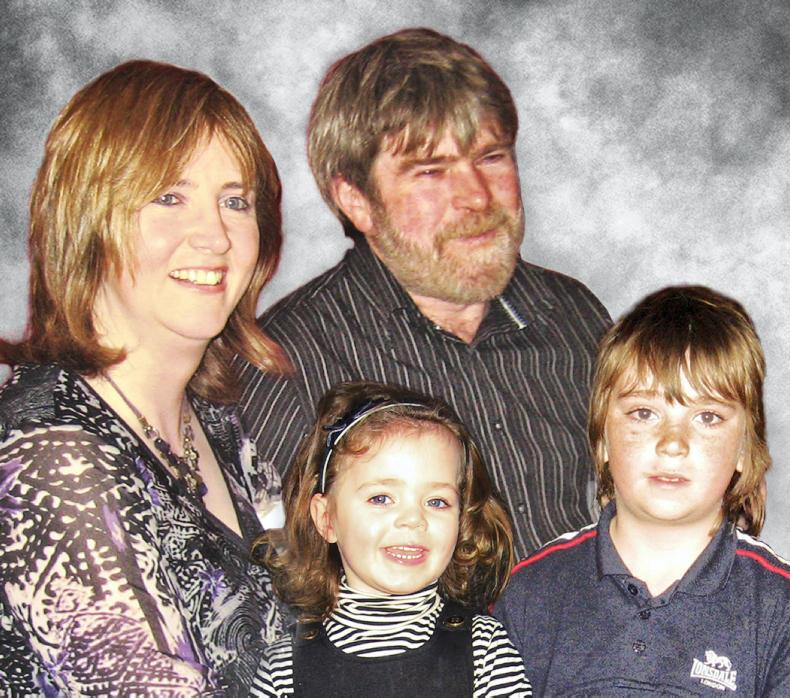

Brendan Kelly on holidays with his children, Ronan and Grace.

“He was a very hard worker, passionate about farming and mad into machinery, so he was a very popular contractor. Somebody told me at the funeral that if there was an awkward corner in the field that they didn’t know how to tackle, Brendan was the man to call.

“The day of the accident was lovely and warm; perfect conditions for silage. I was going to be finishing work the next day for six weeks. As I left the office that evening, throwing my post into the out-tray and smiling, my boss joked: ‘What are you so happy about?’ I had seen Brendan at home at lunch and we had just finalised our holiday plans. That was the last time we spoke.

“Brendan had been about to start baling, but there was a build-up of dust in the machine that had to be released. As he went to release it, the machine collapsed on top of him. He was killed instantly. But when they told me there had been an accident and Brendan was dead, I just remember saying: ‘Are you sure? Are you sure?’ You know, thinking they’d got it wrong.

“The lead-up to the funeral is a bit of a blur. Grace had no clue what was going on. She kept saying: ‘Wake up daddy, wake up.’ The house was filled with people and I remember at one stage I just wanted to go outside and scream my head off, but I felt I couldn’t. No matter where I turned, there were people everywhere.

“What had happened consumed my whole being; but I was trying to stay strong for the kids. You felt that this terrible thing was after happening to you, but life was continuing on for everybody else as normal. I went a long time not wanting to go out to see people, not doing things like grocery shopping. My sisters and my mother were very good to me, but I remember the first time I went out shopping myself and thinking of the stuff I used to buy for Brendan and now I was no longer buying it for him. I found it difficult to get through that first shop.

“Nights were long, lonely and emotional and I spent that time putting together a family tree and also a photobook of Brendan with photos I had been given from his family from when he was a baby. I listened to all those songs relating to the loss of someone and the words would make me cry, especially the Enya song, “if I could be where you are”. I read stories about people who had died and what happened to them at the moment of death. I searched the internet for outside support of people in a similar situation, but found very little.

Angela Hogan with her late partner, Brendan Kelly.

“I was lucky that I was able to take time off work in the civil service; but instantly I was faced with decisions of what to do with the farm. I looked to see if there was some sort of a course I could do, over a short space of time, which would give me the skills I needed to run a farm. What made matters more difficult was the fact that we weren’t married and there was no will in place. Brendan’s farm account was frozen. Being a contractor, he collected a lot of the money due to him towards the end of the year when things weren’t so busy and he paid all his bills also at this time. Because his account was frozen, no funds were available to pay these rather huge bills, so we collected money due to him from his customers. Ninety percent of the farmers paid their dues. With this money the farm bills could be paid and I could continue to run the farm with the help of his brothers, but still his account remained frozen.

“Almost all of the household bills were in Brendan’s name and trying to get them changed to my name proved to be a nightmare, as the person on the other side of the phone could only speak to the account holder or get the solicitor to deal with it. The fear was always there because of our marital situation that the farm would have to be sold to pay any inheritance tax.

“I ended up having to employ two sets of solicitors – a solicitor for myself and a solicitor for the children – and while we were covered by the cohabitants act and had the full support of Brendan’s family, it was a long process. I had a mountain of paper work, solicitors’ letters nearly every day, phone calls; and it took until May 2017 for the court case that finally declared me as spouse. It was very emotional; even the solicitor was crying with me.

“But I believe that there needs to be greater awareness in families about making a will and discussing what should happen to the farm in the event of an accident. I would say to everyone to make a plan in the event of tragedy, especially if one partner is not from a farming background.

“Eventually, I decided to sell off the machinery as it was just getting older and the farm has been leased out, but Ronan is now studying agri-mechanisation at Pallaskenry and is mad for farming. You would think that the accident might have put him off, but he loved going out with Brendan every chance that he could.

“I first came across Embrace Farm (a farm accident support group) when I saw something on Facebook about a remembrance service. I emailed them about our story, and the founder, Brian Rohan, got in touch and explained that there were lots of widows in the same situation, so I went to the remembrance service.

“At the service, they had a leaflet with a survey that asked if you would be interested in attending a counselling session. I decided to attend a group session, and even though none of us knew each other, I felt a connection with the rest of the people in the group and that you could tell your story without being judged.

“After that first remembrance service, Embrace Farm formed a board of directors and this includes representatives from families who have experienced farm accidents, as well as professionals working in the agri industry. I feel very privileged to have been invited to be a director.

“I think it’s important for other women and families to know that there is an organisation there that knows exactly what you are going through. And by sharing my experience, I hope to keep Brendan’s memory alive as well.”

Visit https://embracefarm.com/

Read more

Love and loss: 'Mam was elegant, but with a wild streak'

Goodbye, My Son: Marian O'Mahony on coping with the terminal illness of a child

The news came about 7.30pm. It was the summer holidays so our son, Ronan, had gone off for the day with Brendan, and I was at home with Grace, who would turn three the following month.

“I was on the laptop booking our flights for our family holiday at Christmas. I had put in our four names and was literally on the second page booking in our baggage when a car drove into the yard. It was Brendan’s brother and his brother-in-law. I was saying: ‘Come in, have a cup of tea’; but he told me there had been an accident…

“Brendan and I first met in a pub in Nenagh called The Railway Bar. I used to play traditional music at a session there every Saturday night and he was a customer. Brendan had a great sense of humour. He enjoyed a good yarn and was able to tell one himself. He looked very like the film actor Chuck Norris, so he was regularly stopped for photographs. He was easy going and would never get flustered about anything. I would be the type of person who would panic about things, but he was always able to bring me down to earth. We balanced each other out that way.

“We were living in a house in Nenagh that had a great big yard suitable for tractors to turn in, which was the main reason this house was bought. But the dream was to eventually live on the farm and we had the plans drawn up. He wanted me to look after this, as he used to say that he would be happy to live in a hen house.

“Another dream of his was to live on one of the Canary Islands for the winter months. We were looking at job prospects over there, but he still planned on coming back to Ireland for the summer months to go at silage and corn. He just couldn’t give it up.

Brendan Kelly on holidays with his children, Ronan and Grace.

“He was a very hard worker, passionate about farming and mad into machinery, so he was a very popular contractor. Somebody told me at the funeral that if there was an awkward corner in the field that they didn’t know how to tackle, Brendan was the man to call.

“The day of the accident was lovely and warm; perfect conditions for silage. I was going to be finishing work the next day for six weeks. As I left the office that evening, throwing my post into the out-tray and smiling, my boss joked: ‘What are you so happy about?’ I had seen Brendan at home at lunch and we had just finalised our holiday plans. That was the last time we spoke.

“Brendan had been about to start baling, but there was a build-up of dust in the machine that had to be released. As he went to release it, the machine collapsed on top of him. He was killed instantly. But when they told me there had been an accident and Brendan was dead, I just remember saying: ‘Are you sure? Are you sure?’ You know, thinking they’d got it wrong.

“The lead-up to the funeral is a bit of a blur. Grace had no clue what was going on. She kept saying: ‘Wake up daddy, wake up.’ The house was filled with people and I remember at one stage I just wanted to go outside and scream my head off, but I felt I couldn’t. No matter where I turned, there were people everywhere.

“What had happened consumed my whole being; but I was trying to stay strong for the kids. You felt that this terrible thing was after happening to you, but life was continuing on for everybody else as normal. I went a long time not wanting to go out to see people, not doing things like grocery shopping. My sisters and my mother were very good to me, but I remember the first time I went out shopping myself and thinking of the stuff I used to buy for Brendan and now I was no longer buying it for him. I found it difficult to get through that first shop.

“Nights were long, lonely and emotional and I spent that time putting together a family tree and also a photobook of Brendan with photos I had been given from his family from when he was a baby. I listened to all those songs relating to the loss of someone and the words would make me cry, especially the Enya song, “if I could be where you are”. I read stories about people who had died and what happened to them at the moment of death. I searched the internet for outside support of people in a similar situation, but found very little.

Angela Hogan with her late partner, Brendan Kelly.

“I was lucky that I was able to take time off work in the civil service; but instantly I was faced with decisions of what to do with the farm. I looked to see if there was some sort of a course I could do, over a short space of time, which would give me the skills I needed to run a farm. What made matters more difficult was the fact that we weren’t married and there was no will in place. Brendan’s farm account was frozen. Being a contractor, he collected a lot of the money due to him towards the end of the year when things weren’t so busy and he paid all his bills also at this time. Because his account was frozen, no funds were available to pay these rather huge bills, so we collected money due to him from his customers. Ninety percent of the farmers paid their dues. With this money the farm bills could be paid and I could continue to run the farm with the help of his brothers, but still his account remained frozen.

“Almost all of the household bills were in Brendan’s name and trying to get them changed to my name proved to be a nightmare, as the person on the other side of the phone could only speak to the account holder or get the solicitor to deal with it. The fear was always there because of our marital situation that the farm would have to be sold to pay any inheritance tax.

“I ended up having to employ two sets of solicitors – a solicitor for myself and a solicitor for the children – and while we were covered by the cohabitants act and had the full support of Brendan’s family, it was a long process. I had a mountain of paper work, solicitors’ letters nearly every day, phone calls; and it took until May 2017 for the court case that finally declared me as spouse. It was very emotional; even the solicitor was crying with me.

“But I believe that there needs to be greater awareness in families about making a will and discussing what should happen to the farm in the event of an accident. I would say to everyone to make a plan in the event of tragedy, especially if one partner is not from a farming background.

“Eventually, I decided to sell off the machinery as it was just getting older and the farm has been leased out, but Ronan is now studying agri-mechanisation at Pallaskenry and is mad for farming. You would think that the accident might have put him off, but he loved going out with Brendan every chance that he could.

“I first came across Embrace Farm (a farm accident support group) when I saw something on Facebook about a remembrance service. I emailed them about our story, and the founder, Brian Rohan, got in touch and explained that there were lots of widows in the same situation, so I went to the remembrance service.

“At the service, they had a leaflet with a survey that asked if you would be interested in attending a counselling session. I decided to attend a group session, and even though none of us knew each other, I felt a connection with the rest of the people in the group and that you could tell your story without being judged.

“After that first remembrance service, Embrace Farm formed a board of directors and this includes representatives from families who have experienced farm accidents, as well as professionals working in the agri industry. I feel very privileged to have been invited to be a director.

“I think it’s important for other women and families to know that there is an organisation there that knows exactly what you are going through. And by sharing my experience, I hope to keep Brendan’s memory alive as well.”

Visit https://embracefarm.com/

Read more

Love and loss: 'Mam was elegant, but with a wild streak'

Goodbye, My Son: Marian O'Mahony on coping with the terminal illness of a child

SHARING OPTIONS