The money a co-op makes from processing and selling milk, after it has paid its debt, can only be in two places – the milk price paid to farmers or in the co-op profit. If it is in neither, farmers would be right to ask questions of the long-term strategy and viability of their co-op.

The industry is in an unprecedented period of expansion, coupled with huge swings in global dairy markets.

Over the last three years alone, milk volumes have increased by some 25% and are expected to increase by a further 15% in the next three.

Stainless steel and driers cost money, which can only be paid out of profits which means out of the milk price.

Yes, higher-margin products are an option but the reality is that around 50% of the additional milk has ended up in powder commodity markets.

There is nothing wrong with this, once the structure of the industry behind it matches the leanest and tightest of our competitors, be they in Europe or further afield.

Supports

In credit to the Irish co-op model, as the market didn’t return the price required at farm level to make a profit, the co-ops say they supported milk prices in 2016.

In a year when farmers saw the average price of milk fall 2c/l to 27c/l, this included a support of 1.5c/l to 2c/l, according to the co-ops.

If this support had not been given by the co-ops, the milk price would have been even poorer at around 25c/l on average. This was the market reality in 2016.

But a supported milk price simply means the price a farmer received came directly out of co-op profits. Obviously this can be done for limited periods but it is not a sustainable strategy. It also means the co-op must be making enough profit to provide a support in the first place. If it is not, it will have to take it out of reserves which then impacts the balance sheet.

So what is a sustainable (operating) profit level for a co-op? If supports were not paid last year, processors would have made 3c/l to 4c/l on average, which is a respectable profit level.

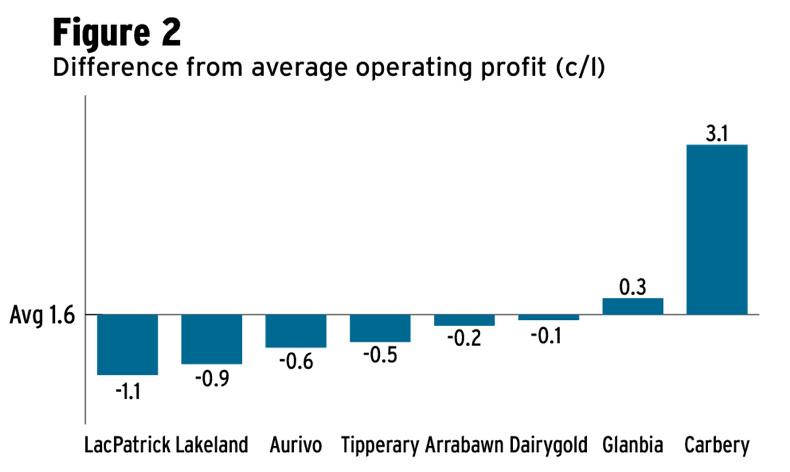

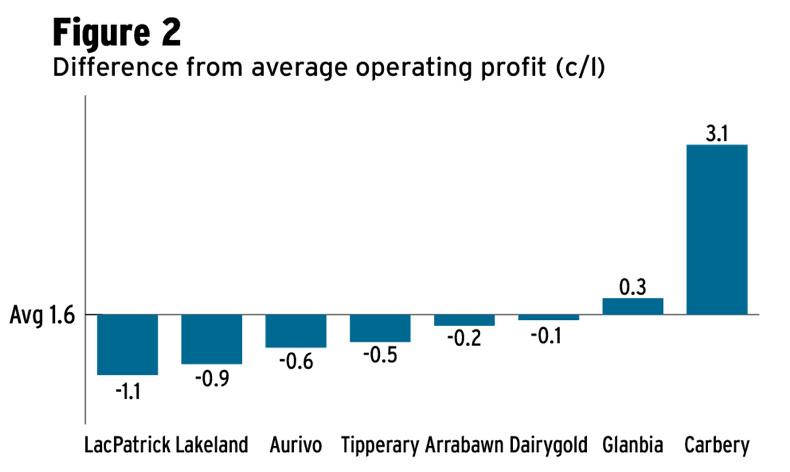

In reality, however, because of supports, it reduced average profits to 1.6c. This profit level is very thin and would not be sustainable to allow for reinvestment and build reserves.

Movement in revenues

No doubt 2016 was a tough year for dairy markets. Despite a 7% increase in milk volumes, turnover across co-ops was down around 2% to 4%. Lakeland was the only processor to record an increase in revenue helped by the Fane Valley acquisition in May 2016.

Depending on the product mix, other processors recorded varying falls in revenues.

For example, Glanbia (GII) and Dairygold which are more heavily weighted towards commodity powders, felt the vagaries of the volatile market. Carbery also saw a fall in turnover, but this mainly related to currency translations.

Liquid milk boosted turnover at Arrabawn as the shelf price of liquid milk remains the same despite weaker dairy markets. Aurivo saw its turnover drop after selling its shareholding in the timber processor ECC.

Movement in profits

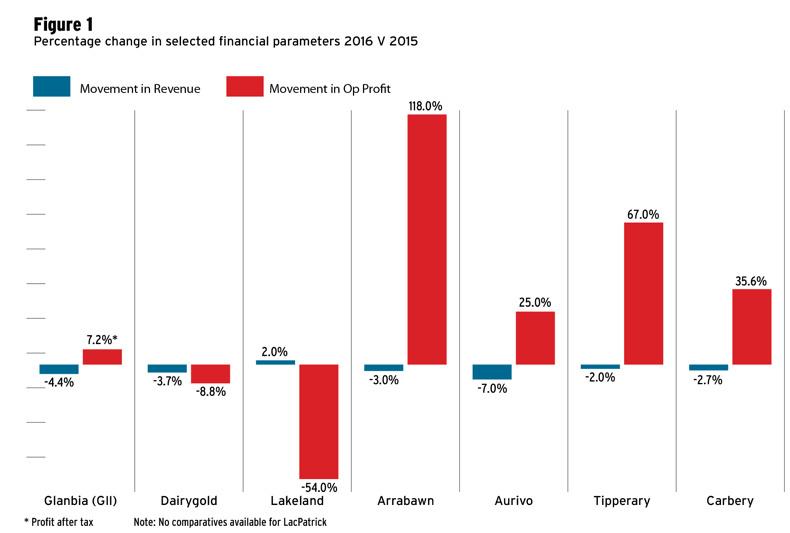

But revenue isn’t profit. Operating profit movements also showed huge degrees of variation (Figure 1). The majority of processors saw increases in profits, despite supporting prices during the year. However, the comparative year of 2015 also saw co-ops support prices to a similar level.

Dairygold and Lakeland were the only co-ops to record a fall in operating profits after they said they supported prices to the tune of €25m (Dairygold) and €16m (Lakeland). Profits at Tipperary were up after an exceptional year in its French business.

Aurivo saw its profits improve, but came from a low base. Profits at Arrabawn also increased significantly as cost savings came on stream along with improved plant utilisation. GII, which makes one of the highest profit margins, increased profits marginally. Carbery also recorded a strong increase in profits on a high margin level, driven by strong performance in its flavours business.

Farmers talk in cents per litre, and to better understand performance of a co-op it was decided to look at operating profit in terms of milk volumes processed. There is a slight disclaimer here in that co-ops also have other businesses which may contribute or affect profit levels. Nonetheless it gives an indication of profitability and where a co-op ranks relative to average performance.

As can be seen from Figure 2, the average profit level is 1.6c/l. GII, which has an in-built profit target of 2c/l along with Carbery, is the only processor above the average. Carbery is no doubt the star performer, delivering 3c/l above average.

This reflects the Carbery model where it returns a large chunk of the profits from its global flavours and ingredients business directly in the milk price. At the other end of the scale, LacPatrick has one of the lowest profit levels, 1c/l lower than the average.

But profit levels cannot be taken in isolation. Farmers need to consider where their co-op is placed on the milk league, where they rank in operating profit (cent per litre) and what level of investment has taken place.

Taking LacPatrick, it has one of the lowest operating profit levels, yet also paid one of the lowest milk prices. This is a co-op that is going through a huge period of change and is now investing after a period of little capital expenditure. In the past 18 months, it has invested some €35m.

Lakeland also ranks low on profit levels and milk price.

However, it hasn’t asked its farmers to provide any funding for the €90m it has invested over the last five years. This was a decision the board took. However, the payment of stainless steel can ultimately only come from one place – milk price.

Aurivo and Tipperary are some 0.5c lower than the average profit level. Dairygold and Arrabawn are achieving average profit levels.

Debt

The year 2016 showed the vulnerability of the sector during weak markets.

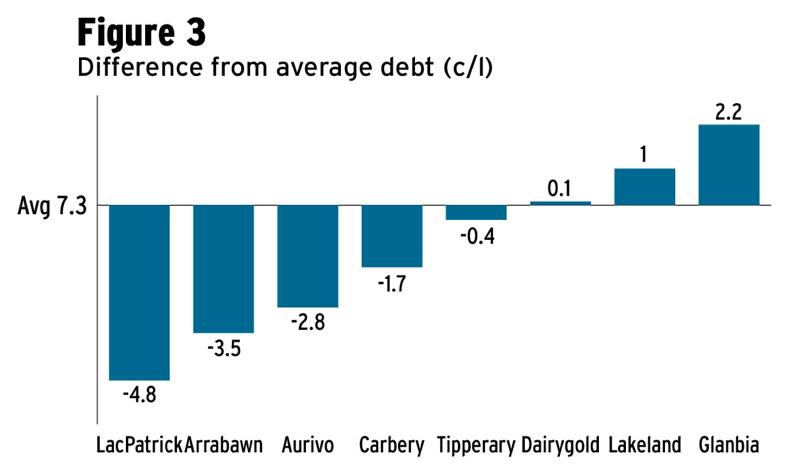

If we take 2016 to be a particularly weak year, with co-ops passing back as much as possible, through supports without making losses or damaging their balance sheets, the average profit level at processing is a thin 1.6c/l. This is not a problem once the co-op is not highly leveraged (overly borrowed) and has manageable debt levels.

The average debt level is 7.3c/l, which means it would take 2.7 years at these earnings levels to pay down all debt. This debt has arisen from the capacity expansion investments made over the last five years.

Almost €750m has been invested by these processors since 2012.

This is impressive considering the expansion and level of supports given over the last two years.

However, even with all the extra capacity, there is growing realisation among processors that further investment in capacity will be required as farmers continue to keep the milk tap flowing.

Board payments

Fees and expenses paid to members of Irish co-op and processor boards came to a cumulative €2.6m in 2016, with 161 individual board members receiving an average payment of more than €16,400 last year.

However, board fees vary hugely from processor to processor.

For instance, there are 18 members on the Lakeland board but no fees are paid. In contrast, there are 22 members on the GII board each receiving an average of almost €50,000 per annum in fees and expenses, which is the highest in the country.

Dairygold follows after GII, with the 12 members of its board paid a total of €383,000, or an average of just under €32,000 per board member. The 28 board members of Kerry co-op receive an average payment of €16,820 per annum in fees and expenses, while in Carbery the average board member gets €16,800.

At the lower end of the scale, Arrabawn and Tipperary co-ops both paid less than €5,000 in fees and expenses to board members.

The 24 board members of LacPatrick received an average of €7,000 last year, while Aurivo board members got €14,000 in fees.

Senior management remuneration

Since 2015, companies have been forced to report the remuneration of senior management under new accounting rules. Aside from the two plcs, this was the first time farmers got sight of pay levels at co-op level.

Excluding the Kerry Group, which does not break down pay for the senior management of its agribusiness division, the combined senior management teams of the remaining processors were paid more than €15.8m in salaries, bonuses, pension contributions and other benefits last year. With management teams varying between eight and 15 people for each of the processors, there are roughly 80 senior managers between the co-ops, excluding Kerry.

This means the average remuneration of a senior manager in an Irish dairy co-op or processor is €200,000.

Milk price review: Lisavaird regains top spot

The review: what it means for farmers

Converting volume to milk solids

KPMG milk review: churning the results

Full coverage of the KPMG / Irish Farmers Journal milk price review

SHARING OPTIONS