Northern Ireland is a success story when it comes to developing an anaerobic digestion (AD) industry from scratch. In the space of a few years, the country went from a handful of commercial and agricultural AD plants to having over 90 in operation today.

Virtually all of these AD plants are producing biogas to power combined heat and power plants and produce electricity. These plants are supported under the Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation which closed in 2017 and will run to 2037.

Northern Ireland (NI) will soon see another wave of AD development but this time, the plants will be upgrading the biogas to biomethane for injection into the gas grid. This was the topic of the recent Anaerobic Digestion and Bioresources Association forum in Northern Ireland.

Scale of development

Under NI’s new climate change legislation, the country has a 2030 target to cut emissions by 48% when compared to a 1990 baseline, and achieve net zero emissions of all greenhouse gases (except methane) by 2050. Similar to the Republic of Ireland (ROI), decarbonising the heat, transport and agricultural sectors will prove particularly challenging, but biomethane is poised to play a role in all three.

The question then turns to where these new plants will be located and how they will be supplied. Arguably the best way to create biomethane is with waste, especially food waste. This should always be the target.

However, waste is very competitive and is already in short supply which poses a challenge. If the sector is to sustainably develop to its full potential, then there is no option but to use agricultural resources. But this is why biomethane offers such an opportunity to the agricultural sector. Essentially, the biomethane sector can’t develop without farmers building, operating and supplying these plants.

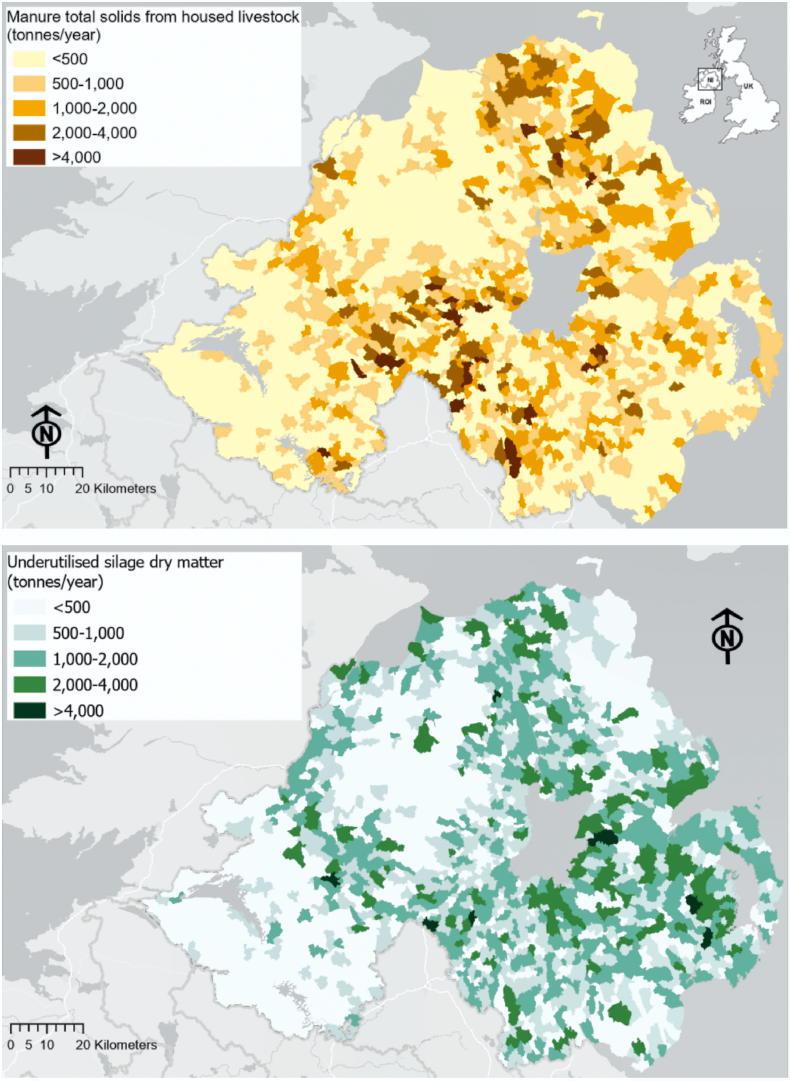

David Rooney of Queens University Belfast spoke at the forum and gave an outline of what agricultural resources are currently available for biomethane production across NI.

Using geospatial analysis, he looked at the volume of slurries and underutilised grass silage which are available across NI to produce biomethane. Underutilised grass silage is defined as the difference between a farm’s silage (DM) requirement and an average dry matter target of 10t DM/ha. Farms producing over 10t DM/ha were excluded.

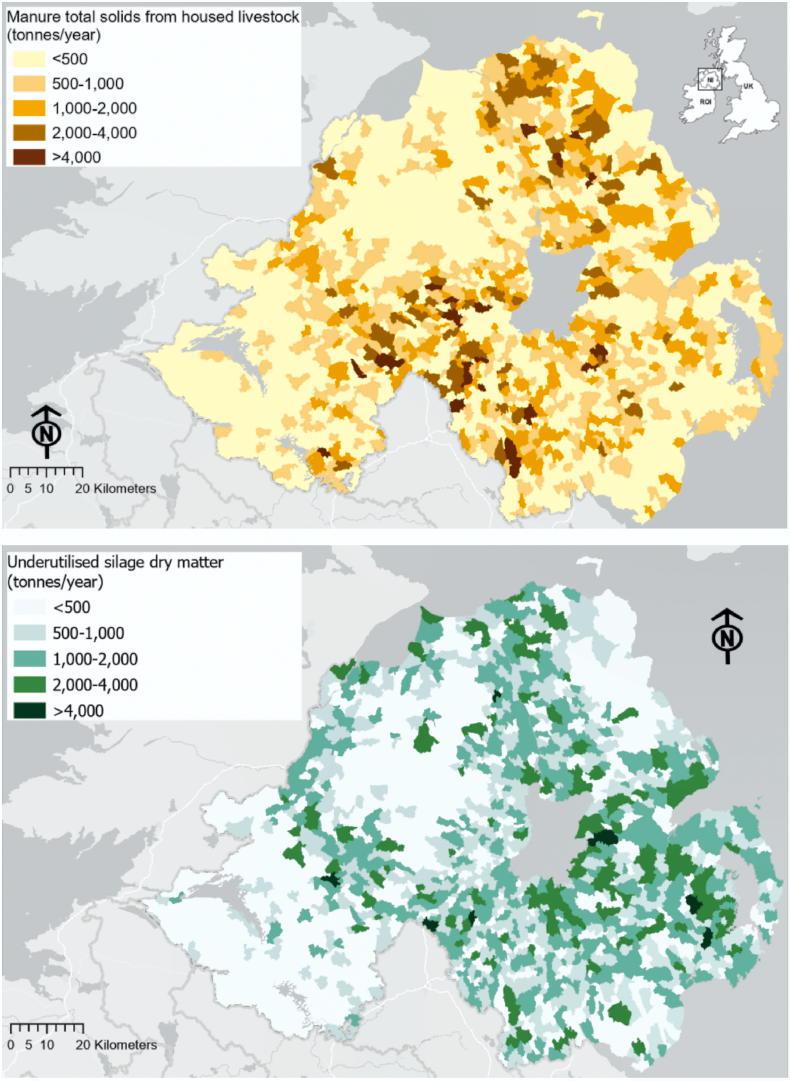

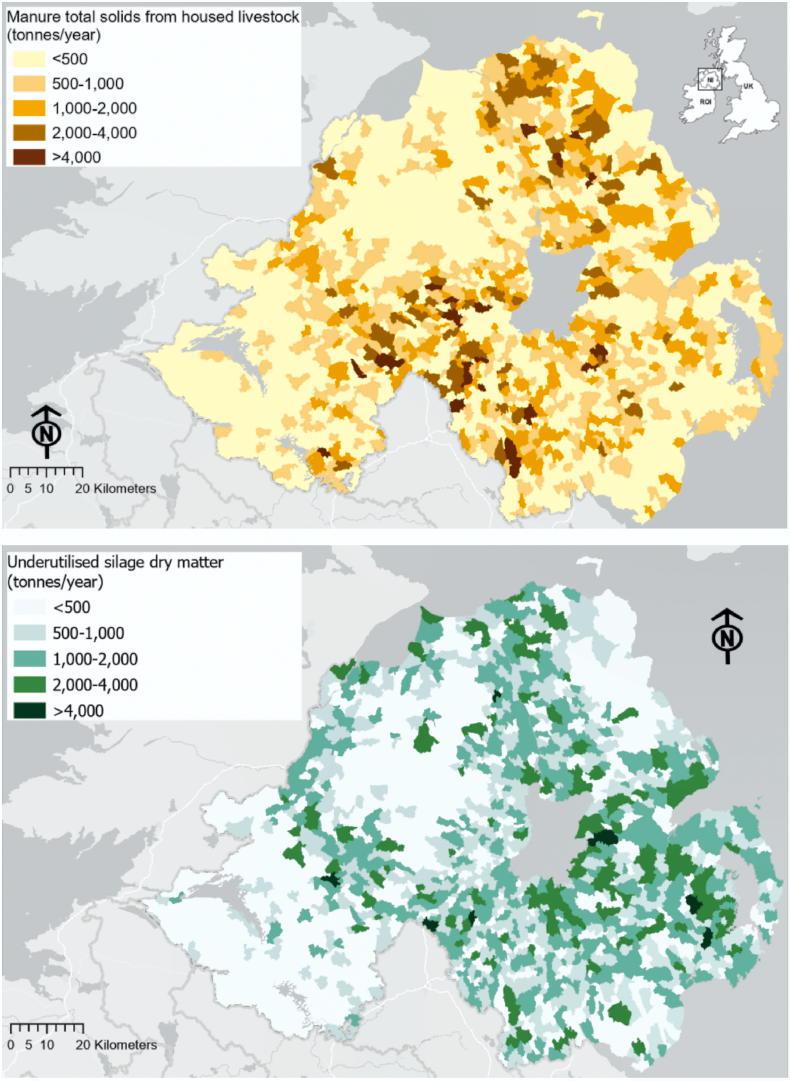

Figure 2 and 3:Map of housed slurry (yellow) and underutilised grass (green)

Figures 2 and 3 shows this data mapped.

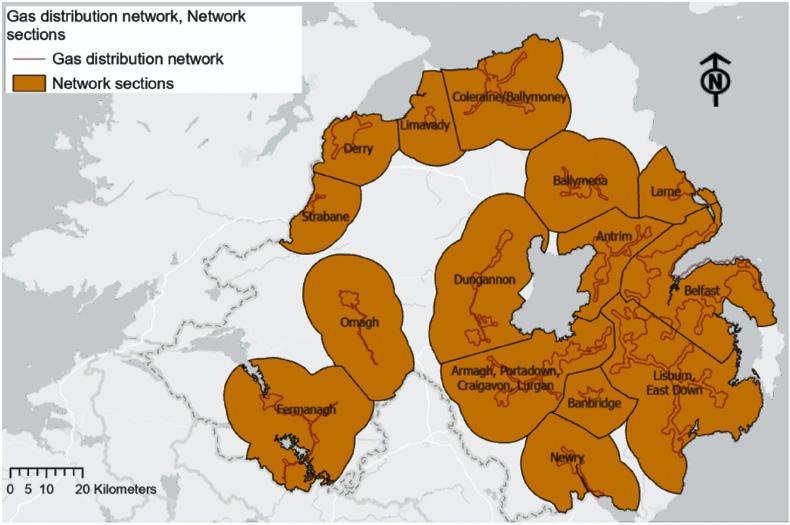

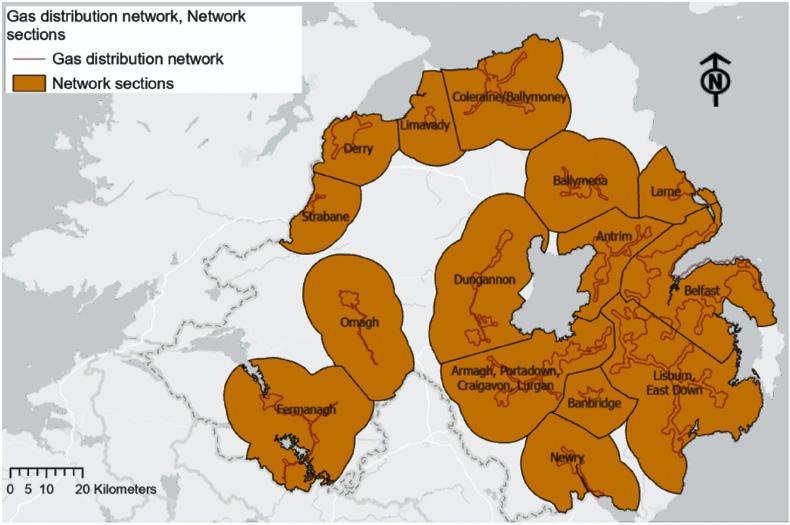

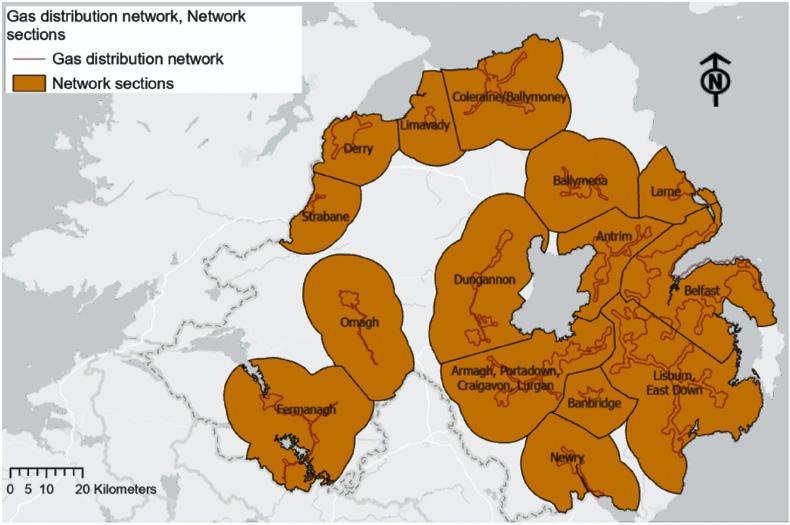

They then considered the infrastructure required to develop an AD plant, namely a gas grid connection, and looked at the slurry and grass silage resources 10km either side of the grid (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Zones around NI gas grid which would see 70 new AD plants develop

The analysis shows there are enough resources in these zones to produce enough biomethane to meet 80% of NI’s gas demand or 6.3TWh worth of biomethane (see Table 1).

Realistic

While this shows what is possible, it’s questionable if it’s realistic. Instead, Russell Smyth of KPMG presented findings from a new report which has yet to be released.

The report outlines how a target of 1.4TWh of biomethane production capacity could be achieved by 2030. This target would require the construction of around 70 new 20gigawatt hours (GWh) AD plants. A 20GWh AD plant refers to the primary output of biomethane from that plant and this would be similar in size to a 1MW AD plant which produces electricity.

A typical plant of that size requires around 1,000ac of grass silage and 10,000-15,000t of slurry.

Seventy biomethane plants would displace about 6% of energy emissions and around 9% of natural gas demand, creating an estimated 1,400 jobs in the process.

However, considering that no biomethane is currently being injected into the gas grid in NI yet (compared to 7TWh in Britain and 32TWh in Europe), the challenge is great. The first grid injection in NI likely won’t happen until next year.

Supports

Similar to ROI, a viable biomethane industry is not possible without government supports and everyone accepted that. A significant amount of work is ongoing with the NI civil service around biomethane development, however.

Minister Gordon Lyons, who opened the conference, announced the establishment of a new inter-departmental biomethane group to explore the development of the technology in NI. The group consists of DAERA, the Department of Economy, the Department of Infrastructure, the Utility Regulator, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute, NI Water and the strategic investment board.

Minister Lyons also outlined how his Department is working to establish a regulated biomethane market specific to NI where the cost to buy and sell biomethane is disconnected from global gas prices.

Russell Smyth said interest from investors in AD is high: “For the first time I’m absolutely confident that a credible biomethane plant can get funding without challenge; that was not the case 12 months ago.”

However, funders will only invest when there is market certainty and a support scheme is essential to this. A typical 20GWh AD plant will cost in excess of €10m to build. Russell outlined three possible designs of schemes which could be put in place to fund the sector:.

Feed-in-tariffs: This is a common scheme design where an AD operator is given a set price for their gas via a tariff. Obligation scheme: An obligation scheme places an obligation on suppliers to source a minimum percentage off renewables. It doesn’t set the price but instead creates demand through a legal obligation. This is the policy with which the ROI is proceeding but Russell questions if this is actually fundable as there is little price certainty. Contracts for difference: This is in operation in the UK electricity market and is likely to be the most suitable for biomethane, explains Russell. The AD operator will bid for a strike price. When the market goes below this price, the government steps in and makes up the difference.

Northern Ireland is a success story when it comes to developing an anaerobic digestion (AD) industry from scratch. In the space of a few years, the country went from a handful of commercial and agricultural AD plants to having over 90 in operation today.

Virtually all of these AD plants are producing biogas to power combined heat and power plants and produce electricity. These plants are supported under the Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation which closed in 2017 and will run to 2037.

Northern Ireland (NI) will soon see another wave of AD development but this time, the plants will be upgrading the biogas to biomethane for injection into the gas grid. This was the topic of the recent Anaerobic Digestion and Bioresources Association forum in Northern Ireland.

Scale of development

Under NI’s new climate change legislation, the country has a 2030 target to cut emissions by 48% when compared to a 1990 baseline, and achieve net zero emissions of all greenhouse gases (except methane) by 2050. Similar to the Republic of Ireland (ROI), decarbonising the heat, transport and agricultural sectors will prove particularly challenging, but biomethane is poised to play a role in all three.

The question then turns to where these new plants will be located and how they will be supplied. Arguably the best way to create biomethane is with waste, especially food waste. This should always be the target.

However, waste is very competitive and is already in short supply which poses a challenge. If the sector is to sustainably develop to its full potential, then there is no option but to use agricultural resources. But this is why biomethane offers such an opportunity to the agricultural sector. Essentially, the biomethane sector can’t develop without farmers building, operating and supplying these plants.

David Rooney of Queens University Belfast spoke at the forum and gave an outline of what agricultural resources are currently available for biomethane production across NI.

Using geospatial analysis, he looked at the volume of slurries and underutilised grass silage which are available across NI to produce biomethane. Underutilised grass silage is defined as the difference between a farm’s silage (DM) requirement and an average dry matter target of 10t DM/ha. Farms producing over 10t DM/ha were excluded.

Figure 2 and 3:Map of housed slurry (yellow) and underutilised grass (green)

Figures 2 and 3 shows this data mapped.

They then considered the infrastructure required to develop an AD plant, namely a gas grid connection, and looked at the slurry and grass silage resources 10km either side of the grid (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Zones around NI gas grid which would see 70 new AD plants develop

The analysis shows there are enough resources in these zones to produce enough biomethane to meet 80% of NI’s gas demand or 6.3TWh worth of biomethane (see Table 1).

Realistic

While this shows what is possible, it’s questionable if it’s realistic. Instead, Russell Smyth of KPMG presented findings from a new report which has yet to be released.

The report outlines how a target of 1.4TWh of biomethane production capacity could be achieved by 2030. This target would require the construction of around 70 new 20gigawatt hours (GWh) AD plants. A 20GWh AD plant refers to the primary output of biomethane from that plant and this would be similar in size to a 1MW AD plant which produces electricity.

A typical plant of that size requires around 1,000ac of grass silage and 10,000-15,000t of slurry.

Seventy biomethane plants would displace about 6% of energy emissions and around 9% of natural gas demand, creating an estimated 1,400 jobs in the process.

However, considering that no biomethane is currently being injected into the gas grid in NI yet (compared to 7TWh in Britain and 32TWh in Europe), the challenge is great. The first grid injection in NI likely won’t happen until next year.

Supports

Similar to ROI, a viable biomethane industry is not possible without government supports and everyone accepted that. A significant amount of work is ongoing with the NI civil service around biomethane development, however.

Minister Gordon Lyons, who opened the conference, announced the establishment of a new inter-departmental biomethane group to explore the development of the technology in NI. The group consists of DAERA, the Department of Economy, the Department of Infrastructure, the Utility Regulator, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute, NI Water and the strategic investment board.

Minister Lyons also outlined how his Department is working to establish a regulated biomethane market specific to NI where the cost to buy and sell biomethane is disconnected from global gas prices.

Russell Smyth said interest from investors in AD is high: “For the first time I’m absolutely confident that a credible biomethane plant can get funding without challenge; that was not the case 12 months ago.”

However, funders will only invest when there is market certainty and a support scheme is essential to this. A typical 20GWh AD plant will cost in excess of €10m to build. Russell outlined three possible designs of schemes which could be put in place to fund the sector:.

Feed-in-tariffs: This is a common scheme design where an AD operator is given a set price for their gas via a tariff. Obligation scheme: An obligation scheme places an obligation on suppliers to source a minimum percentage off renewables. It doesn’t set the price but instead creates demand through a legal obligation. This is the policy with which the ROI is proceeding but Russell questions if this is actually fundable as there is little price certainty. Contracts for difference: This is in operation in the UK electricity market and is likely to be the most suitable for biomethane, explains Russell. The AD operator will bid for a strike price. When the market goes below this price, the government steps in and makes up the difference.

SHARING OPTIONS