The breeding of elite crossbred cattle for exhibition at livestock shows has become a very popular pursuit among a new wave of young enthusiasts, both male and female, and has been instrumental in developing and retaining their interests in farming as well as other related careers including agricultural science and veterinary medicine.

Consistent with all aspects of agriculture and livestock production, those farmers involved in the breeding of elite beef cattle for showing have readily embraced and adopted new developments in scientific discovery in their relentless pursuit to breed the ‘perfect animal’.

Such innovations include reproductive programs for multiple ovulation and embryo transfer (MOET) and more recently in-vitro embryo production (IVP); use of information on the animal’s genome including specific genes and regions of DNA to more consistently select animals with a greater propensity for muscling or indeed coat colour; tailored nutritional and health regimes especially around vaccination and mineral requirements.

The advent of genomic technology, in particular, has facilitated a greater understanding of the genetic control of key traits in livestock production as well as providing tools to improve breeding decisions.

Indeed, Ireland has been to the fore, worldwide, in adopting these breeding innovations and making them available at a national scale. Two traits of particular interest to breeders of show calves are muscling and coat colour and some aspects of the underlying genomic control of these traits are briefly discussed here.

Myostatin gene’s role in controlling muscle development

While the overall muscular development of an animal will be influenced by the actions of many genes in conjunction with its nutritional and health management, myostatin is a gene recognised for its particular influence on body muscle growth and consequently carcass performance.

Under normal circumstances, the myostatin gene acts to control or apply a ‘brake’ on of muscle fibre development.

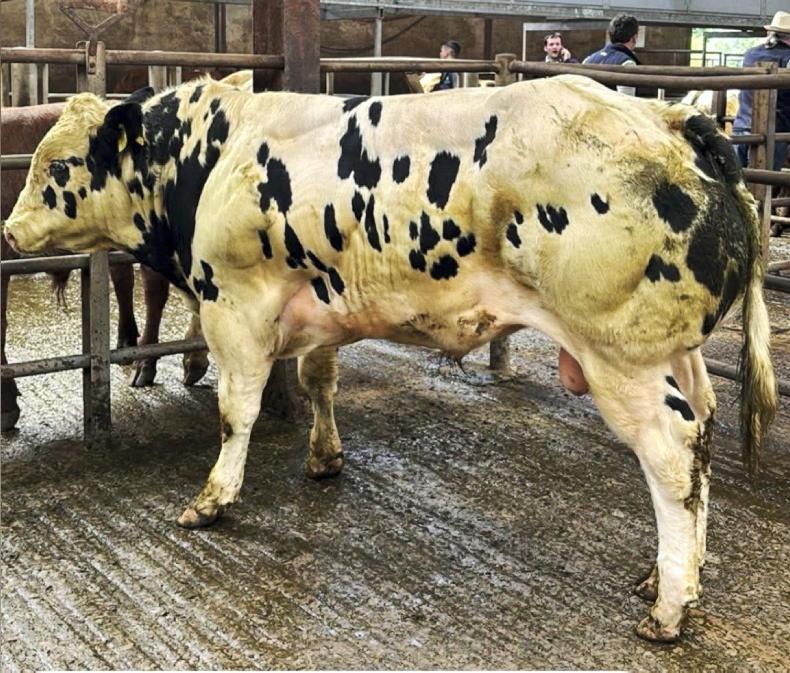

However, the action of a number of ‘mutations’ or abnormalities within the DNA sequence of the myostatin gene can result in the whole or partial loss of function of myostatin activity, leading to increased muscle mass, or the so-called ‘double-muscle’ phenotype.

This latter term is misleading in that cattle exhibiting this increased muscular physique have the same number and type of muscles, but have exaggerated multiplication and development of the constituent muscle fibres, compared with their conventional contemporaries.

Cattle exhibiting the double muscling phenotype have up to 20% more muscle mass than their contemporaries without myostatin mutations.

The extent of increased muscularity and carcase quality and consequences for other traits such as calving difficulty depends on the type and number (one or two) of mutations a calf inherits from its parents.

This has been described for Irish cattle breeds in research by beef cattle geneticist, Dr Cliona Ryan at Teagasc (see Figure 1).

Myostatin gene mutations and how they affect muscle development

Variations or interruptions in the DNA sequence of the myostatin gene occur at specific regions. Currently 21 such known variants are known but the three commonly referred to are: nt821 (mainly found in Belgian Blue), Q204X (mainly found in Charolais), F94L (mainly found in Limousin). These disruptions to the normal DNA sequence of the myostatin gene can have different effects on the extent of muscle development. For example:

Full breaks on the myostatin gene (eg, nt821, Q204X variants) disable the control of muscle growth, causing extreme (double) muscling.Partial breaks on the myostatin gene (eg, F94L mutation) weaken the control of the myostatin gene on muscle growth, resulting in improved muscularity without leading to extreme muscle mass.The importance of understanding the myostatin status of your cattle

Breeders intent on exploiting the undoubted benefits of manipulating the known variants in myostatin gene in order to produce cattle with increased and more consistent muscularity, must be aware of the myostatin gene variant status of the females in the herd as well as the bulls that they wish to use on these females, in order to avoid complications and unintended consequences, not least, calving difficulty.

For example, females that carry two copies of mutations such as nt821 or Q204X may have narrower pelvises, with the increased muscling also interrupting pelvic distension, or ‘springing’ making the birthing process more difficult. This risk is significantly increased if such females are bred to a bull that also carries two copies of the same mutation, as the resulting calf will, undoubtedly, have exaggerated muscle development thus further compounding the problem.

Breeders thus need to be prepared for a higher than normal incidence of veterinary intervention including caesarean section delivery whether their calves are born to their genetic dam or even to a recipient dam through MOET.

In addition to birthing difficulties, cattle exhibiting the ‘double muscled’ physique have been reported to have relatively lower heart and lung mass, a higher susceptibility to respiratory issues and other health problems, greater requirement for vitamin E and selenium (due to greater muscle mass) and potential skeletal abnormalities, such as congenital tendon contracture as well as reduced fertility and smaller genitalia in both males and females. The enlarged tongue muscle mass, typical of calves carrying two copies of myostatin gene mutations (homozygous), often leads to difficulties in the calves’ ability to latch onto the teat which, without considerable intervention, can affect colostrum consumption and subsequent immune status and viability.

Given the importance of maintaining a healthy coat of hair on their animals, another issue of note to show calf producers is the fact that researchers have recently observed an association between the mutation in the myostatin gene and susceptibility to psoroptic mange, a skin disease caused by Psoroptes ovis mites.

This is particularly manifested in the Belgian Blue breed but requires greater vigilance and prophylactic treatments in such cattle.

How is myostatin inherited?

A calf inherits one copy of its myostatin gene from its sire and the second copy from its dam. Thus, if both sire and dam are carriers (have one copy each), the resulting calf could:

Be normal (25% chance),Be a carrier and have one copy of the mutation (50% chance),Have two copies of the mutation (25% chance)—risking extreme calving difficulty if the mutation is either nt821 or Q204X.This random inheritance explains why one cow could have three very different calves when successively bred to the same bull: a normal sized calf, a moderately larger, well muscled calf, and a ‘double-muscled’ calf—all depending on which genes are passed on during each of the three matings.

That is why genotyping both the sire and the dam is essential to plan matings appropriately. Calves can inherit a single copy of two different myostatin gene mutations from each of its parents leading to it having one copy of each of two mutations (ie a single Q204x and a single nt821).

This will also lead to exaggerated muscle development relative to calves not carrying myostatin mutations or inheriting a single copy of one of the variants. Many show calf breeders are now utilising the genomic status of their female cattle for myostatin mutations and strategically selecting sires (across breeds) to mate with these females in order to reduce the incidence of calves carrying homozygous copies of some mutations (ie double nt821 or Q204x) but rather ‘mixing and matching’ to produce calves with a single copy of a particular variant ie one nt821 and one Q204x or a single copy of F94L with either Q204x or nt821.

The status of animals for major genes including myostatin variants can be viewed by logging on to the ICBF website and selecting the genomic herd profile option.

Coat colour

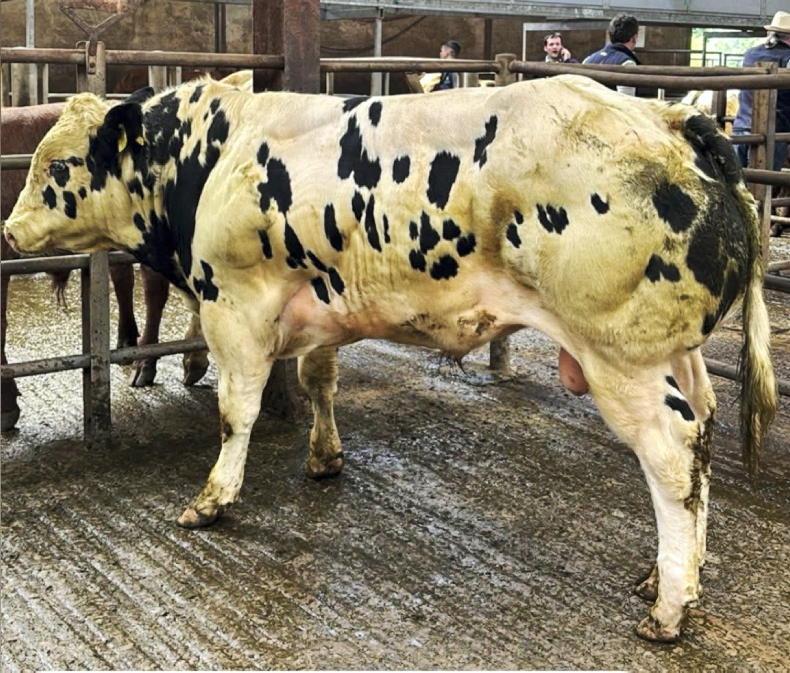

While physique and structural correctness will always be amongst the key breeding goals for show calf producers, aesthetic traits such as coat colour have increasingly become important in recent years.

Though a number of different genes influence coat colour, all animals have one base coat colour, which is either black or red. A gene called the melanocartin 1 receptor is involved in the production of red/black coat colour in cattle. Other colour variations such as spotting, dilution (eg white/grey), roan and brindle (striped pattern) are caused by certain other genes acting to modify this base coat colour.

Breeders need to be aware that breeding for a particular coat colour is not as simple as selecting those animals which visually express that coat colour. Several DNA tests are available that identify the underlying coat colour genetics of an animal, providing increased accuracy and the ability to change coat colour more rapidly than traditional visual selection on phenotype or indeed progeny testing.

The two main alleles for the melanocartin 1 receptor gene are Black (ED) or Red (e), while another allele, Wild Type (E+), is also present in a small percentage of animals (see: https://breedplan.une.edu.au/).

Like the aforementioned situation for the myostatin gene, each animal will inherit two alleles for coat colour, one from each parent, with the Black allele being dominant over both the Red and Wild Type alleles. As the Red allele is recessive, and an animal must carry two copies of the Red allele to have red coat colour.

The roan colour in cattle, is a variation of the above scenario and is caused by a mutation in the KITLG gene (also called the MGF or steel locus gene) on chromosome 5, which results in incomplete dominance and interacts with the melanocartin 1 receptor gene. A roan animal is a heterozygote with one functional KITLG allele and one non-functional allele, resulting in a mixture of coloured and white hairs.

Animals with two functional alleles are solid-coloured (ie Red), while those with two non-functional alleles are white. When these two homozygous genotypes are crossed, all of the resulting calves will be heterozygous having one copy of each allele (R/r) with both coloured and white hairs intermingled, creating the roan phenotype. However, when two heterozygous cattle (ie two roan coated) are crossed, 50% of the progeny will exhibit some element of the roan coat while 25% each of the progeny will exhibit solid colour and white respectively.

Thus, don’t expect that by crossing two roan coated cattle that all of your calves will have a roan coat!

Similar to selecting cattle for myostatin mutations there is some evidence that selection for roan coat colour can lead to a small proportion of animals suffering from potential reproductive abnormalities (ie White Heifer Disease) including anomalies of the female genital tract.

Thus, it is important to remember that like any trait, breeding of cattle for coat colour should always be balanced with selection for other traits of economic and functional importance. This is why the strategic use of information on major genes, coupled with genetic indexes which more comprehensively predict the animals true breeding merit is the best way forward.

The breeding of elite crossbred cattle for exhibition at livestock shows has become a very popular pursuit among a new wave of young enthusiasts, both male and female, and has been instrumental in developing and retaining their interests in farming as well as other related careers including agricultural science and veterinary medicine.

Consistent with all aspects of agriculture and livestock production, those farmers involved in the breeding of elite beef cattle for showing have readily embraced and adopted new developments in scientific discovery in their relentless pursuit to breed the ‘perfect animal’.

Such innovations include reproductive programs for multiple ovulation and embryo transfer (MOET) and more recently in-vitro embryo production (IVP); use of information on the animal’s genome including specific genes and regions of DNA to more consistently select animals with a greater propensity for muscling or indeed coat colour; tailored nutritional and health regimes especially around vaccination and mineral requirements.

The advent of genomic technology, in particular, has facilitated a greater understanding of the genetic control of key traits in livestock production as well as providing tools to improve breeding decisions.

Indeed, Ireland has been to the fore, worldwide, in adopting these breeding innovations and making them available at a national scale. Two traits of particular interest to breeders of show calves are muscling and coat colour and some aspects of the underlying genomic control of these traits are briefly discussed here.

Myostatin gene’s role in controlling muscle development

While the overall muscular development of an animal will be influenced by the actions of many genes in conjunction with its nutritional and health management, myostatin is a gene recognised for its particular influence on body muscle growth and consequently carcass performance.

Under normal circumstances, the myostatin gene acts to control or apply a ‘brake’ on of muscle fibre development.

However, the action of a number of ‘mutations’ or abnormalities within the DNA sequence of the myostatin gene can result in the whole or partial loss of function of myostatin activity, leading to increased muscle mass, or the so-called ‘double-muscle’ phenotype.

This latter term is misleading in that cattle exhibiting this increased muscular physique have the same number and type of muscles, but have exaggerated multiplication and development of the constituent muscle fibres, compared with their conventional contemporaries.

Cattle exhibiting the double muscling phenotype have up to 20% more muscle mass than their contemporaries without myostatin mutations.

The extent of increased muscularity and carcase quality and consequences for other traits such as calving difficulty depends on the type and number (one or two) of mutations a calf inherits from its parents.

This has been described for Irish cattle breeds in research by beef cattle geneticist, Dr Cliona Ryan at Teagasc (see Figure 1).

Myostatin gene mutations and how they affect muscle development

Variations or interruptions in the DNA sequence of the myostatin gene occur at specific regions. Currently 21 such known variants are known but the three commonly referred to are: nt821 (mainly found in Belgian Blue), Q204X (mainly found in Charolais), F94L (mainly found in Limousin). These disruptions to the normal DNA sequence of the myostatin gene can have different effects on the extent of muscle development. For example:

Full breaks on the myostatin gene (eg, nt821, Q204X variants) disable the control of muscle growth, causing extreme (double) muscling.Partial breaks on the myostatin gene (eg, F94L mutation) weaken the control of the myostatin gene on muscle growth, resulting in improved muscularity without leading to extreme muscle mass.The importance of understanding the myostatin status of your cattle

Breeders intent on exploiting the undoubted benefits of manipulating the known variants in myostatin gene in order to produce cattle with increased and more consistent muscularity, must be aware of the myostatin gene variant status of the females in the herd as well as the bulls that they wish to use on these females, in order to avoid complications and unintended consequences, not least, calving difficulty.

For example, females that carry two copies of mutations such as nt821 or Q204X may have narrower pelvises, with the increased muscling also interrupting pelvic distension, or ‘springing’ making the birthing process more difficult. This risk is significantly increased if such females are bred to a bull that also carries two copies of the same mutation, as the resulting calf will, undoubtedly, have exaggerated muscle development thus further compounding the problem.

Breeders thus need to be prepared for a higher than normal incidence of veterinary intervention including caesarean section delivery whether their calves are born to their genetic dam or even to a recipient dam through MOET.

In addition to birthing difficulties, cattle exhibiting the ‘double muscled’ physique have been reported to have relatively lower heart and lung mass, a higher susceptibility to respiratory issues and other health problems, greater requirement for vitamin E and selenium (due to greater muscle mass) and potential skeletal abnormalities, such as congenital tendon contracture as well as reduced fertility and smaller genitalia in both males and females. The enlarged tongue muscle mass, typical of calves carrying two copies of myostatin gene mutations (homozygous), often leads to difficulties in the calves’ ability to latch onto the teat which, without considerable intervention, can affect colostrum consumption and subsequent immune status and viability.

Given the importance of maintaining a healthy coat of hair on their animals, another issue of note to show calf producers is the fact that researchers have recently observed an association between the mutation in the myostatin gene and susceptibility to psoroptic mange, a skin disease caused by Psoroptes ovis mites.

This is particularly manifested in the Belgian Blue breed but requires greater vigilance and prophylactic treatments in such cattle.

How is myostatin inherited?

A calf inherits one copy of its myostatin gene from its sire and the second copy from its dam. Thus, if both sire and dam are carriers (have one copy each), the resulting calf could:

Be normal (25% chance),Be a carrier and have one copy of the mutation (50% chance),Have two copies of the mutation (25% chance)—risking extreme calving difficulty if the mutation is either nt821 or Q204X.This random inheritance explains why one cow could have three very different calves when successively bred to the same bull: a normal sized calf, a moderately larger, well muscled calf, and a ‘double-muscled’ calf—all depending on which genes are passed on during each of the three matings.

That is why genotyping both the sire and the dam is essential to plan matings appropriately. Calves can inherit a single copy of two different myostatin gene mutations from each of its parents leading to it having one copy of each of two mutations (ie a single Q204x and a single nt821).

This will also lead to exaggerated muscle development relative to calves not carrying myostatin mutations or inheriting a single copy of one of the variants. Many show calf breeders are now utilising the genomic status of their female cattle for myostatin mutations and strategically selecting sires (across breeds) to mate with these females in order to reduce the incidence of calves carrying homozygous copies of some mutations (ie double nt821 or Q204x) but rather ‘mixing and matching’ to produce calves with a single copy of a particular variant ie one nt821 and one Q204x or a single copy of F94L with either Q204x or nt821.

The status of animals for major genes including myostatin variants can be viewed by logging on to the ICBF website and selecting the genomic herd profile option.

Coat colour

While physique and structural correctness will always be amongst the key breeding goals for show calf producers, aesthetic traits such as coat colour have increasingly become important in recent years.

Though a number of different genes influence coat colour, all animals have one base coat colour, which is either black or red. A gene called the melanocartin 1 receptor is involved in the production of red/black coat colour in cattle. Other colour variations such as spotting, dilution (eg white/grey), roan and brindle (striped pattern) are caused by certain other genes acting to modify this base coat colour.

Breeders need to be aware that breeding for a particular coat colour is not as simple as selecting those animals which visually express that coat colour. Several DNA tests are available that identify the underlying coat colour genetics of an animal, providing increased accuracy and the ability to change coat colour more rapidly than traditional visual selection on phenotype or indeed progeny testing.

The two main alleles for the melanocartin 1 receptor gene are Black (ED) or Red (e), while another allele, Wild Type (E+), is also present in a small percentage of animals (see: https://breedplan.une.edu.au/).

Like the aforementioned situation for the myostatin gene, each animal will inherit two alleles for coat colour, one from each parent, with the Black allele being dominant over both the Red and Wild Type alleles. As the Red allele is recessive, and an animal must carry two copies of the Red allele to have red coat colour.

The roan colour in cattle, is a variation of the above scenario and is caused by a mutation in the KITLG gene (also called the MGF or steel locus gene) on chromosome 5, which results in incomplete dominance and interacts with the melanocartin 1 receptor gene. A roan animal is a heterozygote with one functional KITLG allele and one non-functional allele, resulting in a mixture of coloured and white hairs.

Animals with two functional alleles are solid-coloured (ie Red), while those with two non-functional alleles are white. When these two homozygous genotypes are crossed, all of the resulting calves will be heterozygous having one copy of each allele (R/r) with both coloured and white hairs intermingled, creating the roan phenotype. However, when two heterozygous cattle (ie two roan coated) are crossed, 50% of the progeny will exhibit some element of the roan coat while 25% each of the progeny will exhibit solid colour and white respectively.

Thus, don’t expect that by crossing two roan coated cattle that all of your calves will have a roan coat!

Similar to selecting cattle for myostatin mutations there is some evidence that selection for roan coat colour can lead to a small proportion of animals suffering from potential reproductive abnormalities (ie White Heifer Disease) including anomalies of the female genital tract.

Thus, it is important to remember that like any trait, breeding of cattle for coat colour should always be balanced with selection for other traits of economic and functional importance. This is why the strategic use of information on major genes, coupled with genetic indexes which more comprehensively predict the animals true breeding merit is the best way forward.

SHARING OPTIONS