It’s a word that was thrown around a lot over the seven weeks of the Nuffield Global Focus Programme that I completed in July of this year. It made me think about it a lot, not because it was topical. I wanted to know what does it actually mean?

China

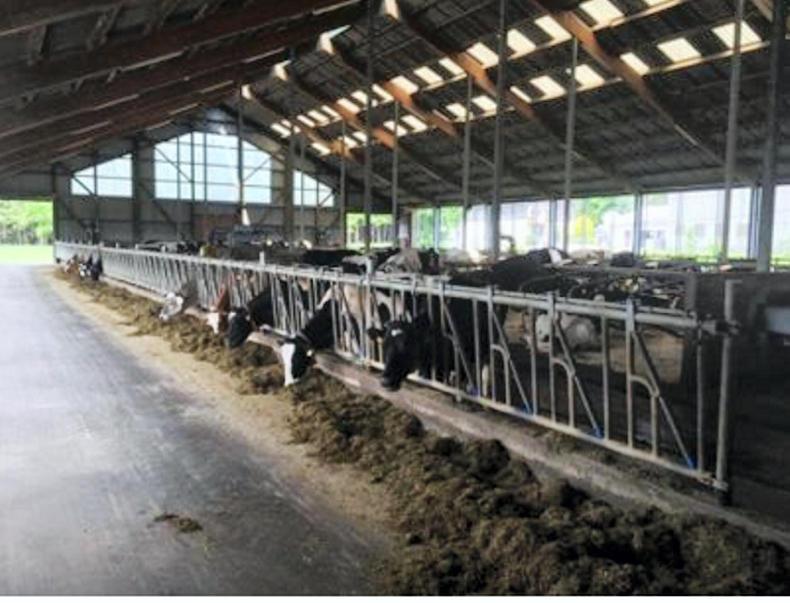

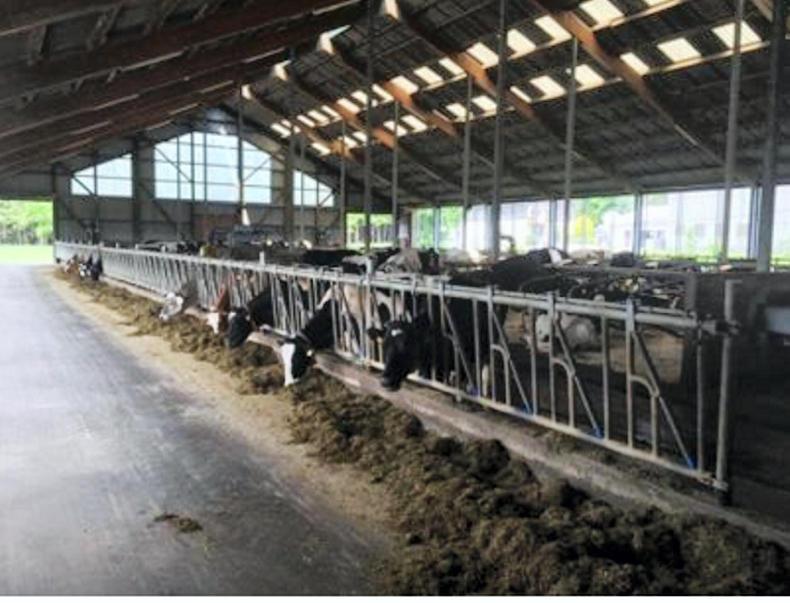

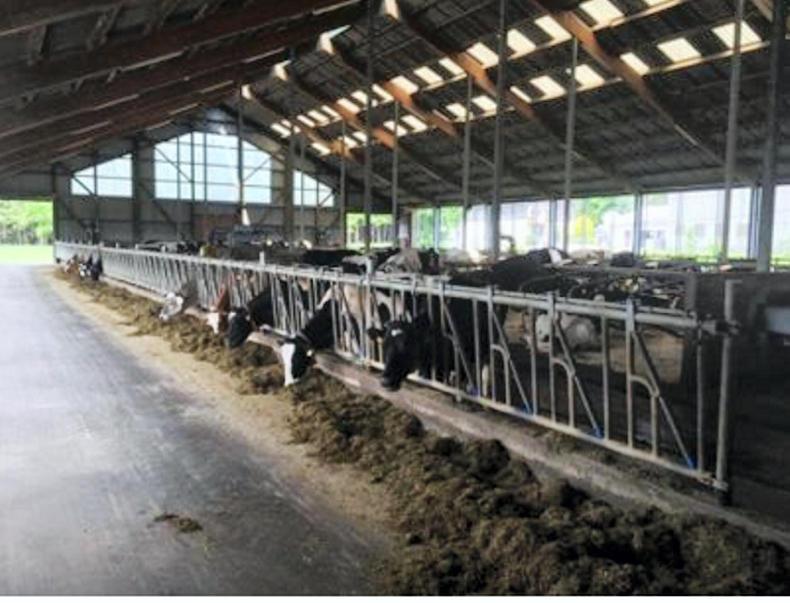

Our group was blown away when we travelled to one of China’s super dairies in the Shandong province.

This 50ha site houses 3,500 cows indoors, which are fed a total mixed ration (TMR) diet consisting of 25% alfalfa imported from California.

The herd itself was black and white, imported from New Zealand.

The cows are producing 33kg of milk at 3.7% butterfat and 3.6% protein, doing 2.4kg solids/head per day.

This was impressive to say the least especially considering this was a first calving herd.

The facilities were superb; purpose-built sheds with bio-digesters and full in-house laboratories with animal health and milk tests provided on site.

Self -sufficient

How could you not be impressed?

The nearest city, Jinan, has a population of eight million people.

With dairy consumption growing rapidly, you could see why the Chinese would want to be self-sufficient and to achieve this in a sustainable way. How could you not be impressed?

The Shandong province, China.

Germany

In Germany, we visited two dairy farms, both indoor, high input-high output, robotic milking farms.

The German work ethic and cleanliness shone through on both of these farms. Everything was done to perfection and appearance always outweighed cost.

Beautiful timber beams, for example, ran the full span of the majority of sheds giving an aesthetic appeal.

On the Schlutke family farm near Handrup, one side of the shed was a clear light roof in an effort to positively affect the cow’s cycle through accessibility to natural light.

This was aided during the winter by LED lights with gradual sunrise and sunset giving 14 hours of daylight all year round.

There was so much light that Christian Schlutke had trees growing inside the shed to prove that it worked. This also gave a natural appeal to the “grand design”.

German 215-cow dairy farm with trees growing indoors.

With both German dairies running on a tight margin of 1c/l to 2c/l, it became evident that they were heavily dependent on their wind turbines, solar panels and bio-digesters to make a margin.

The farms were using slurry and fat waste from factories and restaurants to generate electricity to sell on the grid in a bid to remain financially secure and sustainable for their future generations. Ultimately, it seemed, the cows were a by-product of electricity production.

A German dairy farm producing 2.2m kilowatts of electricity per year with a biogas plant.

The UK

The cows were housed in the lap of luxury in their £7,500/cow/cubicle space, waited on hand and foot

In the UK we visited another robotic dairy, milking 320 Holstein/Norwegian Red/Fleckvieh cross cows. There were six robots milking, two scraping slats and one pushing in silage.

On the shed there was an insulated roof that cost an extra £55,000 to build.

This farm was a sales rep’s dream. The cows were housed in the lap of luxury in their £7,500/cow/cubicle space, waited on hand and foot.

However, at a cost of production of 27p/l and receiving 28p/l, not including the cost of electricity, is this sustainable?

A 320-cow Holstein/Norwegian Red/Fleckvieh cross cow herd in the UK.

California

Then we got to California where we visited two large-scale dairies milking 2,500 Jersey and 3,900 Holstein cows respectively, one more impressive than the next.

On these farms, 70% of the feed comes from corn silage and 30% from concentrate.

Yes, they are producing over 12,000 litres/cow/year with copious amounts of cheap feed, oil and labour but all of this feed is coming from irrigated crops.

With a water table that is depleting by 2.5ft/year, for the last 30 years, is this sustainable?

A pedigree Jersey 2,500 cow herd in Fresno, California.

The irony of where we began and finished our travels was that California is the main supplier of alfalfa to China’s rapidly expanding dairy herd.

That can hardly be sustainable.

So this draws me to my conclusion on sustainability. We, as farmers, need to approach our business in both an economical and most importantly, environmental form of sustainability.

We can’t have one without the other.

Read more

Almond trees taking over from cows in California

New Nuffield scholars announced

It’s a word that was thrown around a lot over the seven weeks of the Nuffield Global Focus Programme that I completed in July of this year. It made me think about it a lot, not because it was topical. I wanted to know what does it actually mean?

China

Our group was blown away when we travelled to one of China’s super dairies in the Shandong province.

This 50ha site houses 3,500 cows indoors, which are fed a total mixed ration (TMR) diet consisting of 25% alfalfa imported from California.

The herd itself was black and white, imported from New Zealand.

The cows are producing 33kg of milk at 3.7% butterfat and 3.6% protein, doing 2.4kg solids/head per day.

This was impressive to say the least especially considering this was a first calving herd.

The facilities were superb; purpose-built sheds with bio-digesters and full in-house laboratories with animal health and milk tests provided on site.

Self -sufficient

How could you not be impressed?

The nearest city, Jinan, has a population of eight million people.

With dairy consumption growing rapidly, you could see why the Chinese would want to be self-sufficient and to achieve this in a sustainable way. How could you not be impressed?

The Shandong province, China.

Germany

In Germany, we visited two dairy farms, both indoor, high input-high output, robotic milking farms.

The German work ethic and cleanliness shone through on both of these farms. Everything was done to perfection and appearance always outweighed cost.

Beautiful timber beams, for example, ran the full span of the majority of sheds giving an aesthetic appeal.

On the Schlutke family farm near Handrup, one side of the shed was a clear light roof in an effort to positively affect the cow’s cycle through accessibility to natural light.

This was aided during the winter by LED lights with gradual sunrise and sunset giving 14 hours of daylight all year round.

There was so much light that Christian Schlutke had trees growing inside the shed to prove that it worked. This also gave a natural appeal to the “grand design”.

German 215-cow dairy farm with trees growing indoors.

With both German dairies running on a tight margin of 1c/l to 2c/l, it became evident that they were heavily dependent on their wind turbines, solar panels and bio-digesters to make a margin.

The farms were using slurry and fat waste from factories and restaurants to generate electricity to sell on the grid in a bid to remain financially secure and sustainable for their future generations. Ultimately, it seemed, the cows were a by-product of electricity production.

A German dairy farm producing 2.2m kilowatts of electricity per year with a biogas plant.

The UK

The cows were housed in the lap of luxury in their £7,500/cow/cubicle space, waited on hand and foot

In the UK we visited another robotic dairy, milking 320 Holstein/Norwegian Red/Fleckvieh cross cows. There were six robots milking, two scraping slats and one pushing in silage.

On the shed there was an insulated roof that cost an extra £55,000 to build.

This farm was a sales rep’s dream. The cows were housed in the lap of luxury in their £7,500/cow/cubicle space, waited on hand and foot.

However, at a cost of production of 27p/l and receiving 28p/l, not including the cost of electricity, is this sustainable?

A 320-cow Holstein/Norwegian Red/Fleckvieh cross cow herd in the UK.

California

Then we got to California where we visited two large-scale dairies milking 2,500 Jersey and 3,900 Holstein cows respectively, one more impressive than the next.

On these farms, 70% of the feed comes from corn silage and 30% from concentrate.

Yes, they are producing over 12,000 litres/cow/year with copious amounts of cheap feed, oil and labour but all of this feed is coming from irrigated crops.

With a water table that is depleting by 2.5ft/year, for the last 30 years, is this sustainable?

A pedigree Jersey 2,500 cow herd in Fresno, California.

The irony of where we began and finished our travels was that California is the main supplier of alfalfa to China’s rapidly expanding dairy herd.

That can hardly be sustainable.

So this draws me to my conclusion on sustainability. We, as farmers, need to approach our business in both an economical and most importantly, environmental form of sustainability.

We can’t have one without the other.

Read more

Almond trees taking over from cows in California

New Nuffield scholars announced

SHARING OPTIONS