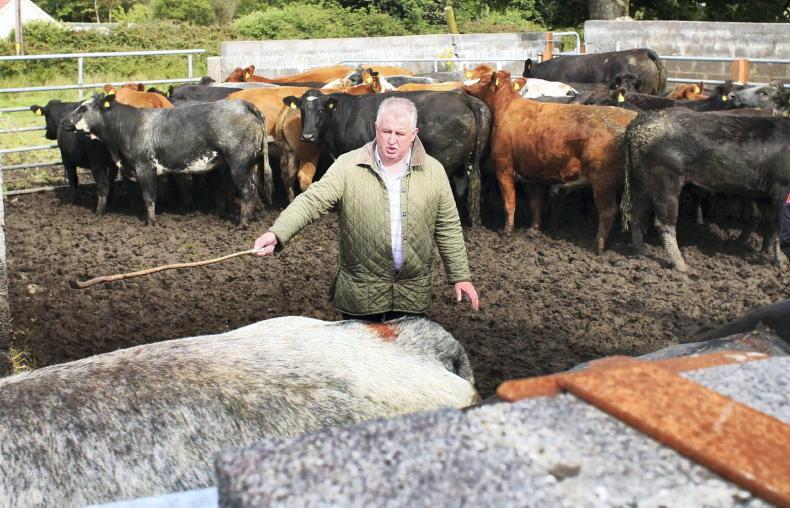

Whether we know it or not, we stand at the forefront in the cattle breeding industry. Through the work of the ICBF and the Department of Agriculture and schemes such as the BDGP, we stand years ahead of most countries.

The ICBF currently has the largest bank of beef genotypes in the world. This, along with talks regarding the role out of DNA registrations from birth, gives Ireland the best chance to utilise the many technologies coming on stream.

Genotyping animals is probably the process people are most familiar with.

A step beyond this is genotyping embryos, which has taken place in the US.

This has the ability to improve breeding programmes by choosing embryos based on sex, the presence of particular traits and the absence of particular diseases.

Genetic gain

Selecting animals with certain traits at the embryo stage can lead to a shorter generation interval, in turn leading to an increase in genetic gain.

This process uses genomic amplification, a way of multiplying DNA cellular information, to generate a genomic profile.

The process of embryo genotyping isn’t perfect, as once an embryo has been biopsied, there is about a 10% risk of pregnancy loss.

Not every embryo can be biopsied. There are different quality grades for embryos. If it’s not a Grade 1, it likely won’t accept a biopsy and freezing. Quality grades for bovine embryos range from grade one, considered excellent, to grade four, dead or degenerating. A grade is assigned based on several criteria, including variation in cell size, shape and colour, or texture of the fluid within cell walls.

In 2018, the first of this kind of technology hit the mainstream, when a recipient carrying a genotyped pedigree Angus embryo hit the American market at $11,500.

Through Ireland’s genotype database, this technology, if adapted, could lead to massive strides in the cattle breeding sector.

Gene editing

Gene editing goes one step further than genotyping or even cloning. It allows producers to select traits they like from one particular animal or breed and add it to another. This is particularly relevant for traits associated with survival or climate.

In July 2018, the first gene-edited calf was born in Brazil.

Brazilian beef generally comes from the Zebu breed, due to its ability to withstand the high summer temperatures.

However, this beef tends to be lean and tough.

The Angus breed, renowned for its meat quality, would fail to survive in Brazil’s climate.

With this in mind, scientists from the biotech company Recombinetics isolated the gene for heat tolerance in the Senepol breed and tried to incorporate it into an Angus embryo.

The Angus breed, renowned for its meat quality, would fail to survive in Brazil’s climate

The procedure took cells from a Red Angus cow and used gene-editing technology called Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALEN) to modify its DNA. This deleted a single base pair from the chromosome sequence to make the Angus replicate the Senepol breed’s heat tolerance.

Then the gene-edited embryo was inserted into a recipient cow. This resulted in the birth of Genzelle, an Angus calf genetically engineered to withstand Brazil’s harsh climate. Although Genzelle is capable of withstanding heat, she can also lay down fat and carries all the meat qualities of the Angus breed.

Scientists say this accelerated breeding programme is identical to a traditional programme, but doesn’t require lots of money and decades of work before delivering results.

The biggest issue in gene-edited animals is whether they will be considered genetically modified organisms (GMOs). If considered GMOs, then as with cloned animals, they would currently not be allowed in to the EU foodchain.

Cloning

Cloning, while not common, does take place in certain parts of the world. The technology first came to light in 1997, when Dolly the sheep was cloned.

Animal cloning is a form of reproduction that does not require the union of a sperm and an egg.

The most common animal cloning technique is somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), where the nucleus of an immature egg cell is replaced with that of a cell from a body part (somatic cell) such as an ear, leg, nose, etc.

Once nuclear replacement has been completed, the reconstructed embryo is artificially activated and then transferred to a surrogate mother, where the foetus develops.

This allows breeders to essentially recreate special individuals, whether it be top producers or animals lost too early due to injury, etc.

Identical

The resulting animals will be identical to the donor. This means a simple ear punch is all that is needed to preserve the genotype of an animal for future use.

The cost of producing a clone can vary depending on the volume of animals produced. In general, bovine cloning starts at around $20,000 per calf.

SHARING OPTIONS