Gut worms can be an issue in grazing cattle and can negatively impact performance in grazing cattle. In cattle systems, gut worm control is largely dependent on the availability of effective wormers or anthelminthics.

Research has already been carried out in Ireland on sheep farms and widespread resistance was found to certain classes of wormers.

To date, little work has been carried out on cattle farms but some would suggest that it is only a matter of time before resistance develops on on these farms.

Grazing cattle are naturally exposed to gut worms through grazing infected pastures. A large number of different gut worm species can infect cattle but most follow a similar life cycle, with eggs laid by adult female worms in the gastrointestinal tract passed out with the dung.

The eggs hatch to L1 larvae which feed on microbes in the dung and then progress to L3 (infective stage). L3 migrate out of the dung onto the grass where they can survive for months before being ingested by grazing cattle.

Once ingested, they travel to their preferred site of infection where they further develop into mature adults which lay eggs.

The most important gut worm infecting cattle in Ireland is Ostertagia ostertagi, which is found in the abomasum, and Cooperia oncophera, which is found in the small intestine.

Gut worms can cause disease including scour and ill-thrift in calves but more commonly they are associated with reduced intakes and sub-clinical disease resulting in reduced growth rates.

In the first grazing season, gut worms are generally a bigger problem for dairy calves than for suckler beef calves as grazed grass forms a larger part of the dairy calf’s diet.

Worm larvae accumulate on pasture over the grazing season and worms are generally a greater problem in the second half of the grazing season.

After their first grazing season, cattle usually develop sufficient immunity to prevent clinical disease but heavy infections can still have an impact on performance.

Control

Control of gut worms is generally achieved by giving broad-spectrum anthelmintics (wormers).

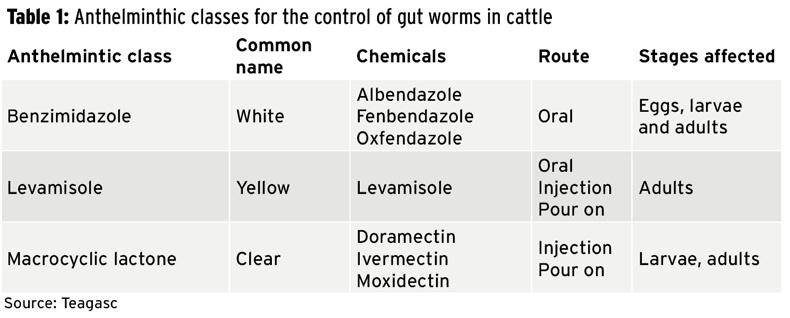

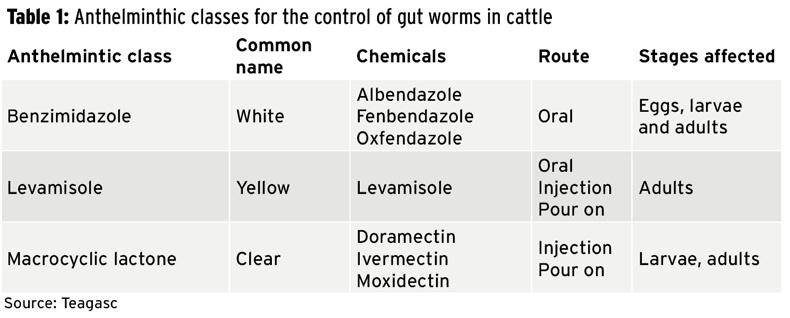

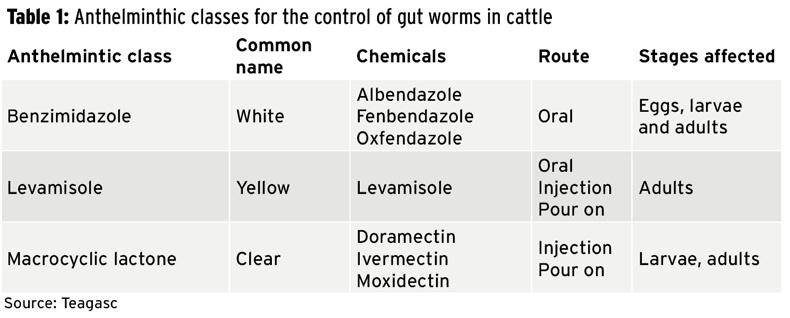

Despite the large number of anthelmintic products on the market, there are currently only three classes of wormer licenced in Ireland for the control of gut worms in cattle and all products fall into one of these classes. These classes are:

1 Benzimidazole (commonly known as white wormer).

2 Levamisole (commonly known as yellow wormer).

3 Macrocyclic lactones (commonly known as clear wormer).

Anthelmintic resistance refers to the ability of worms to survive a dose that should kill them. Table 1 outlines the different classes of drugs available in Ireland to control gutworm.

Resistance

Anthelmintic resistance has only recently been detected on cattle farms in Ireland. Anthelmintic resistance is a heritable trait which resistant worms pass on to their offspring. When animals are treated with an anthelmintic, all susceptible worms are killed, allowing only resistant worms to survive which results in resistant worms making up a greater proportion of the worm population in subsequent generations.

Therefore, the continuous use of anthelmintics can lead to the development of anthelmintic resistance. It is important that anthelmintics are used appropriately to help slow the development of anthelmintic resistance.

Anthelmintic resistance can be diagnosed on-farm by a faecal egg count reduction test. This involves collecting dung samples from 10 to 20 randomly selected calves and determining the faecal egg count for each calf. Calves are then treated with the product to be tested.

Dung samples are collected from the same calves after treatment (seven days post-treatment for levamisole; 14 days post-treatment for benzimidazole and macrocyclic lactone) and the egg count carried out.

The reduction in egg count after treatment is a measure of the effectiveness of the anthelmintic treatment.

A fully effective anthelmintic dose reduces egg count to zero after administration. If the egg count reduction is less than 95%, then anthelmintic resistance is considered to be present.

Teagasc Study

The Teagasc study was carried out on 24 dairy calf-to-beef farms in Ireland in 2017 and 2018. The worm burden of the herd was monitored every two weeks by taking a pooled dung sample and determining the faecal egg count.

Calves were weighed and a dung sample collected from each calf.

For each anthelmintic to be tested (benzimidazole, levamisole, ivermectin or moxidectin), 20 calves were treated at the appropriate dose rate. Seven days (levamisole) or 14 days (benzimidazole, ivermectin and moxidectin) after treatment dung samples were again collected from each calf.

Faecal egg count was determined for all samples and the reduction in egg count post-treatment calculated.

On all 17 trial farms where ivermectin was tested, resistance was present as treatment failed to reduce the egg count by more than 95%.

On 12 of 17 farms tested (71%) benzimidazole resistance was identified; while 3 of 12 (25%) were found to have levamisole resistance and 9 of 12 (75%) farms with moxidectin resistance. Resistant Cooperia and Ostertagia could be identified.

Dosing advice

Following on from the results of this trial, how should worm control change on Irish beef farms?

Keep the cleanest grazing paddocks (reseeded paddocks or silage aftergrass for young calves.Graze young calves ahead of older stock in a leader/follower system.Mixed grazing with sheep can help to reduce worm burdens.Ensure calves are well fed and not nutritionally challenged as this can increase worm problems.Only dose when necessary and use weight gain or faecal egg counts as a tool to decide.If the faecal egg counts goes above 200 eggs per gram a dose is needed.Check dosing equipment to make sure it is delivering the correct dose.Avoid using the same class of wormer on a continuous basis.Only use combination products where treatment for fluke and worms is needed.

Gut worms can be an issue in grazing cattle and can negatively impact performance in grazing cattle. In cattle systems, gut worm control is largely dependent on the availability of effective wormers or anthelminthics.

Research has already been carried out in Ireland on sheep farms and widespread resistance was found to certain classes of wormers.

To date, little work has been carried out on cattle farms but some would suggest that it is only a matter of time before resistance develops on on these farms.

Grazing cattle are naturally exposed to gut worms through grazing infected pastures. A large number of different gut worm species can infect cattle but most follow a similar life cycle, with eggs laid by adult female worms in the gastrointestinal tract passed out with the dung.

The eggs hatch to L1 larvae which feed on microbes in the dung and then progress to L3 (infective stage). L3 migrate out of the dung onto the grass where they can survive for months before being ingested by grazing cattle.

Once ingested, they travel to their preferred site of infection where they further develop into mature adults which lay eggs.

The most important gut worm infecting cattle in Ireland is Ostertagia ostertagi, which is found in the abomasum, and Cooperia oncophera, which is found in the small intestine.

Gut worms can cause disease including scour and ill-thrift in calves but more commonly they are associated with reduced intakes and sub-clinical disease resulting in reduced growth rates.

In the first grazing season, gut worms are generally a bigger problem for dairy calves than for suckler beef calves as grazed grass forms a larger part of the dairy calf’s diet.

Worm larvae accumulate on pasture over the grazing season and worms are generally a greater problem in the second half of the grazing season.

After their first grazing season, cattle usually develop sufficient immunity to prevent clinical disease but heavy infections can still have an impact on performance.

Control

Control of gut worms is generally achieved by giving broad-spectrum anthelmintics (wormers).

Despite the large number of anthelmintic products on the market, there are currently only three classes of wormer licenced in Ireland for the control of gut worms in cattle and all products fall into one of these classes. These classes are:

1 Benzimidazole (commonly known as white wormer).

2 Levamisole (commonly known as yellow wormer).

3 Macrocyclic lactones (commonly known as clear wormer).

Anthelmintic resistance refers to the ability of worms to survive a dose that should kill them. Table 1 outlines the different classes of drugs available in Ireland to control gutworm.

Resistance

Anthelmintic resistance has only recently been detected on cattle farms in Ireland. Anthelmintic resistance is a heritable trait which resistant worms pass on to their offspring. When animals are treated with an anthelmintic, all susceptible worms are killed, allowing only resistant worms to survive which results in resistant worms making up a greater proportion of the worm population in subsequent generations.

Therefore, the continuous use of anthelmintics can lead to the development of anthelmintic resistance. It is important that anthelmintics are used appropriately to help slow the development of anthelmintic resistance.

Anthelmintic resistance can be diagnosed on-farm by a faecal egg count reduction test. This involves collecting dung samples from 10 to 20 randomly selected calves and determining the faecal egg count for each calf. Calves are then treated with the product to be tested.

Dung samples are collected from the same calves after treatment (seven days post-treatment for levamisole; 14 days post-treatment for benzimidazole and macrocyclic lactone) and the egg count carried out.

The reduction in egg count after treatment is a measure of the effectiveness of the anthelmintic treatment.

A fully effective anthelmintic dose reduces egg count to zero after administration. If the egg count reduction is less than 95%, then anthelmintic resistance is considered to be present.

Teagasc Study

The Teagasc study was carried out on 24 dairy calf-to-beef farms in Ireland in 2017 and 2018. The worm burden of the herd was monitored every two weeks by taking a pooled dung sample and determining the faecal egg count.

Calves were weighed and a dung sample collected from each calf.

For each anthelmintic to be tested (benzimidazole, levamisole, ivermectin or moxidectin), 20 calves were treated at the appropriate dose rate. Seven days (levamisole) or 14 days (benzimidazole, ivermectin and moxidectin) after treatment dung samples were again collected from each calf.

Faecal egg count was determined for all samples and the reduction in egg count post-treatment calculated.

On all 17 trial farms where ivermectin was tested, resistance was present as treatment failed to reduce the egg count by more than 95%.

On 12 of 17 farms tested (71%) benzimidazole resistance was identified; while 3 of 12 (25%) were found to have levamisole resistance and 9 of 12 (75%) farms with moxidectin resistance. Resistant Cooperia and Ostertagia could be identified.

Dosing advice

Following on from the results of this trial, how should worm control change on Irish beef farms?

Keep the cleanest grazing paddocks (reseeded paddocks or silage aftergrass for young calves.Graze young calves ahead of older stock in a leader/follower system.Mixed grazing with sheep can help to reduce worm burdens.Ensure calves are well fed and not nutritionally challenged as this can increase worm problems.Only dose when necessary and use weight gain or faecal egg counts as a tool to decide.If the faecal egg counts goes above 200 eggs per gram a dose is needed.Check dosing equipment to make sure it is delivering the correct dose.Avoid using the same class of wormer on a continuous basis.Only use combination products where treatment for fluke and worms is needed.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: