Last week’s article from the Teagasc Hill Sheep Conference detailed strategies for improving the productivity of Scottish Blackface flocks. A similar theme of improving the productivity of hill flocks was explored at the recent AgriSearch farm walk on the farm of Joe and Seamus Maginn, Ballagh Road, Newcastle, Co Down.

The farm is part of a network of flocks in Northern Ireland that are adopting and trialling new research principles at farm level under the AgriSearch programme (production orientated, farmer-funded research).

Joe’s farm is located on the foothills of the Mourne Mountains with land type varying from good quality lowland to land designated as less favoured area (LFA) to common hill grazing extending from 1,000ft 3,000ft above sea level. The common grazing environment can be described as ‘harder hills’ where the vegetation is natural grazing of heather, wild grasses.

Breeding strategy

The ewe flock comprises 1,000 Blackface ewes, 200 crossbred ewes and 200 Blackface hoggets. The breed make-up is mainly Scottish Blackface but Texel rams are also used to improve growth rates and Swaledale for hardiness. The more difficult nature of the hill grazing areas provide the ideal setting to test the AFBI, Hillsborough, trial of breeding more efficient hill ewes.

The trial investigates the potential of crossbreeding in increasing ewe fertility and lamb growth performance – two vital factors influencing potential farm profitability.

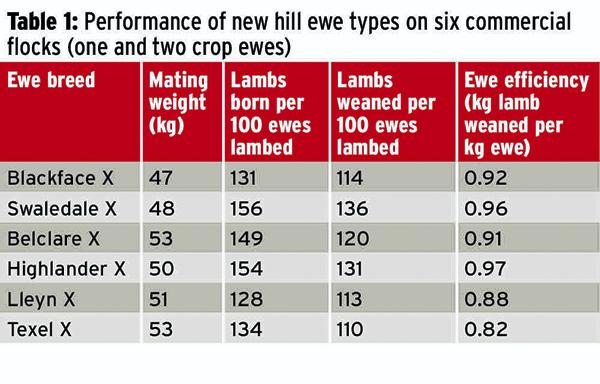

There are six breed crosses being trialled on six commercial flocks. The crosses and average performance across the six farms are listed in Table 1. According to Aurelie Aubry, AFBI, the ‘white faced’ crosses of Belclare and Highlander rams and Scottish Blackface ewes have the potential to increase breeding efficiency by 15% to 20% compared with Scottish Blackface ewes bred pure. The Texel and Lleyn crosses performed below this level and failed to achieve comparable performance to the Scottish Blackface cross.

Tough environment

Explaining his experience of the crosses, Seamus Maginn said that while the ‘white faced’ crosses had the potential to deliver more lambs than the pure Blackface ewes, they were not suited to the harder hills.

He said that the higher mature weight meant ewes had a higher intake requirement and lost condition much quicker than the Blackface or Swaledale sheep.

“The ewes need feeding and won’t look for feed in the same way as the Blackface or Swaledale sheep. The condition falls off them much quicker and they need to be taken off the hills earlier or they won’t survive,’’ he said.

The Swaledale cross Blackface ewe performed particularly well, achieving the highest number of lambs born and weaned.

However, Aurelie pointed out that as the animals are still young, the litter size of the ‘white-faced’ crosses should increase as the ewes get older.

The progeny of these animals may also be more saleable in a store situation or reach French carcase weights easier.

However, the fact remains that these crosses are not suited to the ‘hard’ hills. CAFRE sheep adviser Eileen McCloskey specialises in hill sheep grazing.

She said that the ‘white faced’ crosses performed relatively well during the summer, or where grazing the greener hills.

However, she said that the mileage in the breed’s productivity on harder hills was during the summer only and when it came to overwintering in more difficult conditions, there was not as much value in these crosses.

Eileen added that the Blackface and Swaledale ewes also grazed a much wider area and grazed a higher proportion of heather, a feature that is important in maintaining the area in a productive manner.

Taking these facts into account, the recommended breeding strategies for the harder type hills is a criss-cross breeding pattern between the Scottish Blackface and Swaledale, as shown in Figure 1. For the more favourable hills or green upland areas, a three-breed rotation is being investigated. The aim is to select replacements that combine prolificacy, easy-care traits and carcase traits. This breed cross is also seen as suitable for breeding more efficient lowland ewes with improved maternal traits.

Maternal replacements

Putting in place a recording and identification protocol is key to identifying replacements in a commercial setting that possess the required maternal characteristics. Researchers at Hillsborough have released a lambing booklet and a lamb liveweight book that facilitates easier recording of key traits for easier care management and important production data.

Traits recorded in the booklet include lambing ease, mothering ability and lamb viability characteristics as well as any general problems the ewe experiences such as udder problems or insufficient colostrum.

Recording the data requires lambs to receive a permanent identification.

The recommended method is to tag lambs but where farmers do not want to tag lambs at birth, numbers can be sprayed on the lambs with lambs tagged at a later stage.

Ear notching can also be used to permanently identify suitable replacements.

The lambing book is returned to AFBI Hillsborough who will then produce a free summary report for the flock and send a second book to record lamb performance. The records are combined to produce a final report ranking ewes on their breeding suitability.

Feeding ewes

On the Maginn farm, all ewes are grazed on the mountain in mid-pregnancy. Ewes are scanned at the end of February with lambing starting in mid-April. Single-bearing ewes are returned to the mountain and offered feed blocks until lambing starts. Twin-bearing ewes, or those in poor condition at scanning,are moved to upland grazing and have access to silage and feed blocks. Seamus says that the majority of white-faced crossbreed ewes are in this category.

The quality of silage saved in 2013 analysed 66D-value or DMD, 10.6 ME MJ/kg DM, 22% dry matter and 13.1% crude protein. Feed blocks offered are high in energy and protein which increases the overall energy content of the diet and promotes adequate colostrum production. Ewes are grouped in flocks of about 50 and are supplemented in small land parcels. Remaining ground is given a rest period to allow grass to accumulate for grazing ewes lambing outdoors.

Seamus says that feeding ewes adequately in the run-up to lambing and having grass available is central to reducing workload and minimising mortality. “We generally have enough grass in spring which is critical for us in reducing lambing issues, cases of mismothering and mortality at birth and in early lactation. Our target is to monitor ewes lambing by just taking a quick drive around sheep and letting them work away themselves. The Blakface and Swaledale crosses are excellent for this and, in many cases, the hardest job is to catch the lambs if you need to permanently identify and record data.

‘‘If you neglect ewes and don’t feed them, all you will end up with is having to handle far more ewes, hungry lambs (insufficient colostrum/milk) and mounting mortality,” says Seamus.

Discussing the option of outdoor lambing, Eileen McCloskey (pictured) said trials undertaken in Hillsborough over the last four to five years had returned numerous tips.

In the trials, ewes were housed over the main winter feeding period (December to February) and released outdoors to paddocks with a good cover or fresh grass measuring 5cm to 6cm.

Eileen said fresh spring grass of this type, with good utilisation levels, has a good energy value of approximately 12ME MJ/kg DM and is ideally suited to meeting the energy and protein demand of twin bearing ewes in late pregnancy.

She added that the best scenario is where ewes are released outdoors approximately two weeks pre-lambing to get accustomed to the change in diet and satisfy the higher nutritional demands of ewes in late pregnancy at a reduced cost.

She added that it was not recommended to let single bearing ewes out to comparable quality grass as this would only result in lambs becoming too big, leading to significant lambing difficulties. In Hillsborough, the single-bearing ewes are retained indoors with triplet-bearing ewes to improve the opportunities for cross fostering. The recommended stocking rate at a grass height of 5cm to 6cm and good grazing conditions is five ewes per acre.

SHARING OPTIONS