After Scotland being free of BSE for almost a decade, the finding of a case last week on the farm of Thomas Jackson at Boghead Farm in Lumsden, meant the issue returned to headlines of the mainstream news again. If farming makes mainstream media, it is usually because it is bad news.

What will it mean for Scottish farmers?

For farmers selling cattle in the marts and to the factories, nothing will change on a day-to-day basis. What the finding of an isolated case of BSE means is that the international categorisation of Scotland’s BSE status is revised downwards from “negligible risk” to “controlled risk”. The BSE status of a country is determined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), and is based on a series of risk assessments. The OIE is the inter-governmental organisation responsible for improving animal health worldwide across all animal diseases, not just BSE. It is recognised as a reference organisation by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and currently has a total of 180 member countries.

For BSE, there are three levels of risk:

Negligible risk – which is the best category to be in, and where Scotland along with Northern Ireland had been since May 2017. Controlled risk – the next best level and where Scotland and Northern Ireland had been up until May last year. Undetermined risk – where a country cannot demonstrate it qualifies for one of the other categories. This is rare as most countries where the disease has occurred have procedures and controls in place.Losing negligible risk status because of an isolated BSE discovery isn’t unique to Scotland. In June 2015, the Republic of Ireland, who had just achieved negligible risk classification at the annual meeting of OIE in May of that year, also lost its status because a case of classical BSE was found in a cow in Co Louth.

France had a similar experience prior to that when a single case meant downgrading from negligible to controlled risk. Both countries have remained in this category since while England and Wales at no point achieved negligible risk status and have continued to trade internationally as a controlled risk region.

Northern Ireland who achieved negligible risk at the same time as Scotland in May last year, is now the only region of the British Isles that retains it.

Different types of BSE

Just as there is a distinction by OIE in different risk categories of countries, so too there is different types of BSE. This case in Scotland is determined as Classic BSE which is associated with meat and bone meal feeding in the 1990s though this practice was banned when BSE was at its peak.

The alternative type is a typical BSE which is a random finding which can occur in older cattle. Brazil had a couple examples of this in 2013 but because it was atypical, their negligible risk status was not impacted.

Impact on markets

One of the risks considered by both Scotland and Northern Ireland at the time of their negligible risk status in 2016 was: what if a case of BSE was found and negligible risk status was lost? Bear in mind when Scotland became eligible to apply for negligible risk, the Republic of Ireland experience of having the negligible risk and losing it within a matter of a few weeks was still very fresh in the mind.

The decision to proceed was taken on the basis that the export market impact between negligible and controlled risk was minimal. Of course as negligible risk is the best classification that is possible to achieve, it is more desirable and creates a marketing or brand advantage. However, both the UK and Ireland were able to open international markets and retain these while operating under controlled risk BSE status.

Two of the best examples are Ireland getting access to the USA and China while classified as controlled risk.

Downside to losing negligible risk status

There are however downsides of not having negligible BSE risk, one that is related to the production process, the other being an age limit for the meat, particularly in Asian markets. In these, beef or offal will only be accepted from cattle under 30 months.

Similarly in the production process, offal or by-products that are in anyway connected with the animal’s nervous system have to go for more costly disposal when a country or region is operating under controlled risk status. If it is a negligible risk status, many of these can be harvested and a value realised as opposed to paying a cost of disposal.

After Scotland being free of BSE for almost a decade, the finding of a case last week on the farm of Thomas Jackson at Boghead Farm in Lumsden, meant the issue returned to headlines of the mainstream news again. If farming makes mainstream media, it is usually because it is bad news.

What will it mean for Scottish farmers?

For farmers selling cattle in the marts and to the factories, nothing will change on a day-to-day basis. What the finding of an isolated case of BSE means is that the international categorisation of Scotland’s BSE status is revised downwards from “negligible risk” to “controlled risk”. The BSE status of a country is determined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), and is based on a series of risk assessments. The OIE is the inter-governmental organisation responsible for improving animal health worldwide across all animal diseases, not just BSE. It is recognised as a reference organisation by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and currently has a total of 180 member countries.

For BSE, there are three levels of risk:

Negligible risk – which is the best category to be in, and where Scotland along with Northern Ireland had been since May 2017. Controlled risk – the next best level and where Scotland and Northern Ireland had been up until May last year. Undetermined risk – where a country cannot demonstrate it qualifies for one of the other categories. This is rare as most countries where the disease has occurred have procedures and controls in place.Losing negligible risk status because of an isolated BSE discovery isn’t unique to Scotland. In June 2015, the Republic of Ireland, who had just achieved negligible risk classification at the annual meeting of OIE in May of that year, also lost its status because a case of classical BSE was found in a cow in Co Louth.

France had a similar experience prior to that when a single case meant downgrading from negligible to controlled risk. Both countries have remained in this category since while England and Wales at no point achieved negligible risk status and have continued to trade internationally as a controlled risk region.

Northern Ireland who achieved negligible risk at the same time as Scotland in May last year, is now the only region of the British Isles that retains it.

Different types of BSE

Just as there is a distinction by OIE in different risk categories of countries, so too there is different types of BSE. This case in Scotland is determined as Classic BSE which is associated with meat and bone meal feeding in the 1990s though this practice was banned when BSE was at its peak.

The alternative type is a typical BSE which is a random finding which can occur in older cattle. Brazil had a couple examples of this in 2013 but because it was atypical, their negligible risk status was not impacted.

Impact on markets

One of the risks considered by both Scotland and Northern Ireland at the time of their negligible risk status in 2016 was: what if a case of BSE was found and negligible risk status was lost? Bear in mind when Scotland became eligible to apply for negligible risk, the Republic of Ireland experience of having the negligible risk and losing it within a matter of a few weeks was still very fresh in the mind.

The decision to proceed was taken on the basis that the export market impact between negligible and controlled risk was minimal. Of course as negligible risk is the best classification that is possible to achieve, it is more desirable and creates a marketing or brand advantage. However, both the UK and Ireland were able to open international markets and retain these while operating under controlled risk BSE status.

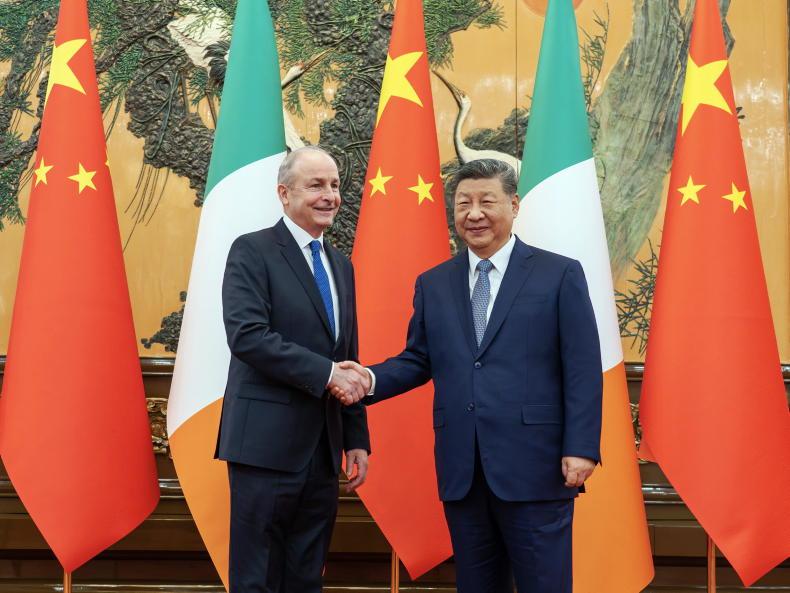

Two of the best examples are Ireland getting access to the USA and China while classified as controlled risk.

Downside to losing negligible risk status

There are however downsides of not having negligible BSE risk, one that is related to the production process, the other being an age limit for the meat, particularly in Asian markets. In these, beef or offal will only be accepted from cattle under 30 months.

Similarly in the production process, offal or by-products that are in anyway connected with the animal’s nervous system have to go for more costly disposal when a country or region is operating under controlled risk status. If it is a negligible risk status, many of these can be harvested and a value realised as opposed to paying a cost of disposal.

SHARING OPTIONS