Our dairy industry has been world class in harnessing the potential of genetics. The key profit-driving traits of calving ease, fertility and milk solids were targeted with laser-like focus through the EBI – with an estimated €1.5bn in genetic gain to farmers in 15 years. The result has not only been a production model that is competitive by international standards but one that, since the abolition of quotas, has been scaled up rapidly and profitably.

In February 2010, 274,000 dairy cows calved down. In 2018, the figure stood at 538,000 and is set to increase again in 2019.

While some of this growth has been driven by new entrants, most reflects expansion of existing dairy herds.

Data from the ICBF shows that these expanding herds followed industry advice and placed an even greater focus on calving ease – the result being an increase use of sires with a calving difficulty of less than 3%.

This restless focus on the key profit-driving traits has and will continue to deliver more functional and profitable replacements into the dairy herd. However, outside of the parlour, it is creating a problem that no part of the dairy sector can afford to ignore.

Figures presented at the Teagasc beef conference by the ICBF’s Andrew Cromie identified an ongoing decline in the quality of beef-bred animals coming from the dairy herd. Since 2014, the percentage of beef-bred dairy carcase grading O- or less has doubled. In the case of Friesian- and Jersey-sired calves, 70% and 80% respectively graded O- or less in 2018, meaning the bulk of meat from these carcases was only suitable for mince.

The vast bulk of Jersey-bred calves are also failing to achieve suitable carcase weights. The trend is hardly surprising given that, as Adam Woods reported last week, seven of the top 10 sires used in the Irish dairy herd were negative for carcase weight.

As a result, the economic viability of the dairy-beef model is seriously challenged – mainly due to light carcase weights and poor carcase conformation significantly reducing output and the value of the end product.

Also this week, Adam Woods looks at how both issues challenged the profitability of the dairy-beef enterprise on Tullamore Farm. After fixed costs and labour, the loss stood at €173/head, albeit that performance was affected by weather.

Slaughtering young calves has been suggested. This would be a short-term fix with long-lasting consequences

These challenges come as the numbers of dairy-bred calves is rising. ICBF figures show that 25% of dairy farms retain calves on farm with bulls and beef-bred heifers brought to beef. Nevertheless, there will still be in the region of 600,000 beef-bred calves and dairy bull calves transferred off dairy farms next spring.

It is imperative for the dairy sector that a viable production model is developed to bring these calves to beef. Slaughtering young calves has been suggested as a solution. This would be a short-term fix with long-lasting negative consequences. Given our brand image, we cannot allow for a bobby calf industry to be developed as a byproduct of dairy.

Breeding programme

So, what do we do? First, the dairy industry has to realise that the focus of the breeding programme has to extend outside the parlour. It must take into account the quality of the calves being transferred into beef.

The dairy-beef index due to be introduced next year will be a useful tool but dairy farmers must be encouraged to use. Industry has a role in driving change. We have seen milk price bonuses introduced by other processors and retailers in the EU designed to incentivise enhanced welfare standards and other consumer-facing measures.

The Bord Bia SDAS would appear the most obvious scheme in which to incorporate calf-welfare measures for which dairy farmers could be rewarded in the milk price. Any scheme should include measures that ensure calves are being transferred off farms in a healthy condition and that the breeding programme in participating herds is focused on improving the beef value of calves.

However, the extension of the SDAS alone will not address the issue. Genetics must be identified to enhance beef traits without undermining advances in dairy breeding.

Establishing a national DNA calf registration strategy needs to be explored. It would require the genotyping of the cow herd. With setup costs in the region of €40m and annual costs of €28m, it is not cheap. The dividends to dairy and beef farmers would have to be established. There would also have to be recognition across all stakeholders that the dividends would extend beyond the farm gate and therefore so should the investment required.

To date, the investment focus associated with abolition of quota has been on increased processing capacity and the direct costs associated with herd expansion. It is time to broaden this to make sure all parts of the jigsaw are in place. The dairy sector has real skin in the game when it comes to ensuring beef-bred dairy calves do not become worthless. Those crossbreeding also need to accept that they may have to share some of the dividend from their breeding policy with the farmer that is prepared to take the bull calves through to beef.

Trade: deal on unfair trading a step in right direction

European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan.

After an intense period of negotiations between the EU institutions, white smoke has emerged on a deal on Unfair Trading Practices (UTP).

This was an attempt, led by European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan, to try to rebalance the power in the food chain – where we have a scenario that sees farmers having the lowest share of the value despite having most of the work, while retail takes half the value for a cash sale business and a short time on the shelf.

Securing support across the EU was quite a challenge and critics of the deal maintain that the measures under the UTP are so diluted that they are meaningless from a farmer’s perspective. While it is true farmers would want more, the widespread opposition to the Commissioner’s initiative from supermarket representatives would indicate that the UTPs will play some role in rebalancing the supply chain.

Rather than condemn for not going far enough, this is a case of where it was better to light a candle than curse the dark. The UTP legislation may be more modest than farmers might want but it is the most that can be achieved at this point. We should welcome it as a worthy first step and seek to build on it.

Trimming: Creed agrees to publish names of factories for over-trimming

Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed.

Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed has agreed with the IFA to publish the names of meat factories fined for over-trimming carcases in 2017.

Farmer attention will focus on these plants. However, the bigger picture is that in agreeing to publish the names, the minister has taken the first step in delivering improved transparency.

The next steps involve putting a robust oversight policy in place. Recently, Commissioner Hogan told farmers that technology exists for farms to be photographed by satellite three times per week. It is not tenable to say that the necessary technology is not available to allow farmers to view their carcases prior to grading and weighing. Factories have an opportunity to demonstrate a real commitment to transparency.

This should extend beyond beef into sheep. Farmers have reacted angrily to the refusal by Irish Country Meats to provide details on clipping charges and the imposition of these clipping charges on all farmers.

Vet dispute: farmers cannot be used as pawns

As we report in our front page story this week, a dispute between the Department of Agriculture and Veterinary Ireland is starting to cause disruption to the flow of animals through abattoirs.

It appears that Veterinary Ireland, representing private vets who provide inspection services within abattoirs for the Department, has escalated a long-running dispute at a time to cause maximum disruption, at one of the busiest slaughtering periods across the various sectors.

Regardless of the issues, both parties cannot allow farmers to be caught in the crossfire and used as pawns in the negotiations.

Private vets have a huge responsibility to these farmers, depending on them for the primary source of income, while the Department has a clear responsibility to ensure the provision of adequate services to allow for proper functioning of the sector. We expect to see a speedy resolution.

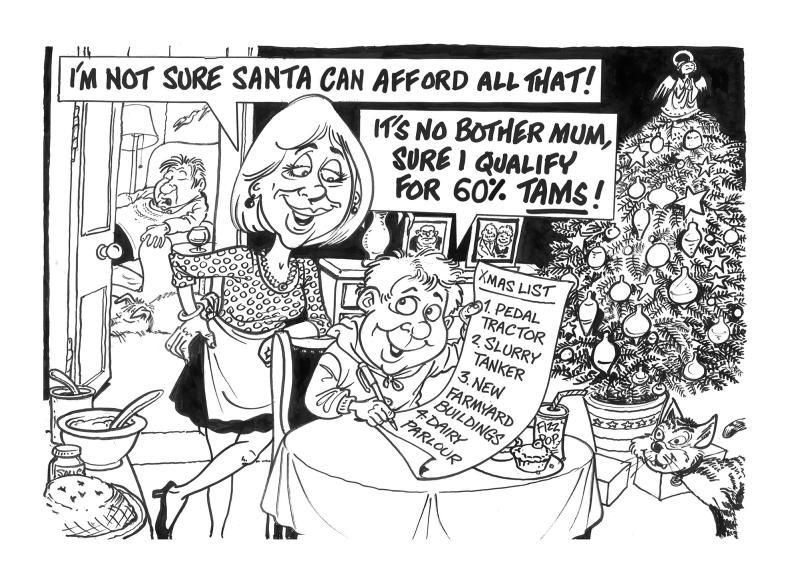

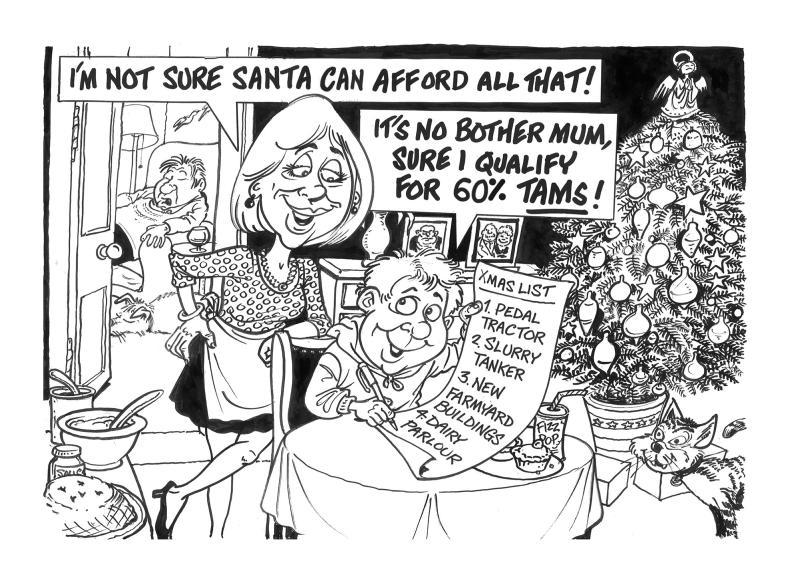

Season’s greetings: Happy Christmas

The team in the Irish Farmers Journal would like to thank you all for your support through the year and wish you and your families a safe and enjoyable Christmas. We will be out next Thursday as normal with daily updates on farmersjournal.ie.

Our dairy industry has been world class in harnessing the potential of genetics. The key profit-driving traits of calving ease, fertility and milk solids were targeted with laser-like focus through the EBI – with an estimated €1.5bn in genetic gain to farmers in 15 years. The result has not only been a production model that is competitive by international standards but one that, since the abolition of quotas, has been scaled up rapidly and profitably.

In February 2010, 274,000 dairy cows calved down. In 2018, the figure stood at 538,000 and is set to increase again in 2019.

While some of this growth has been driven by new entrants, most reflects expansion of existing dairy herds.

Data from the ICBF shows that these expanding herds followed industry advice and placed an even greater focus on calving ease – the result being an increase use of sires with a calving difficulty of less than 3%.

This restless focus on the key profit-driving traits has and will continue to deliver more functional and profitable replacements into the dairy herd. However, outside of the parlour, it is creating a problem that no part of the dairy sector can afford to ignore.

Figures presented at the Teagasc beef conference by the ICBF’s Andrew Cromie identified an ongoing decline in the quality of beef-bred animals coming from the dairy herd. Since 2014, the percentage of beef-bred dairy carcase grading O- or less has doubled. In the case of Friesian- and Jersey-sired calves, 70% and 80% respectively graded O- or less in 2018, meaning the bulk of meat from these carcases was only suitable for mince.

The vast bulk of Jersey-bred calves are also failing to achieve suitable carcase weights. The trend is hardly surprising given that, as Adam Woods reported last week, seven of the top 10 sires used in the Irish dairy herd were negative for carcase weight.

As a result, the economic viability of the dairy-beef model is seriously challenged – mainly due to light carcase weights and poor carcase conformation significantly reducing output and the value of the end product.

Also this week, Adam Woods looks at how both issues challenged the profitability of the dairy-beef enterprise on Tullamore Farm. After fixed costs and labour, the loss stood at €173/head, albeit that performance was affected by weather.

Slaughtering young calves has been suggested. This would be a short-term fix with long-lasting consequences

These challenges come as the numbers of dairy-bred calves is rising. ICBF figures show that 25% of dairy farms retain calves on farm with bulls and beef-bred heifers brought to beef. Nevertheless, there will still be in the region of 600,000 beef-bred calves and dairy bull calves transferred off dairy farms next spring.

It is imperative for the dairy sector that a viable production model is developed to bring these calves to beef. Slaughtering young calves has been suggested as a solution. This would be a short-term fix with long-lasting negative consequences. Given our brand image, we cannot allow for a bobby calf industry to be developed as a byproduct of dairy.

Breeding programme

So, what do we do? First, the dairy industry has to realise that the focus of the breeding programme has to extend outside the parlour. It must take into account the quality of the calves being transferred into beef.

The dairy-beef index due to be introduced next year will be a useful tool but dairy farmers must be encouraged to use. Industry has a role in driving change. We have seen milk price bonuses introduced by other processors and retailers in the EU designed to incentivise enhanced welfare standards and other consumer-facing measures.

The Bord Bia SDAS would appear the most obvious scheme in which to incorporate calf-welfare measures for which dairy farmers could be rewarded in the milk price. Any scheme should include measures that ensure calves are being transferred off farms in a healthy condition and that the breeding programme in participating herds is focused on improving the beef value of calves.

However, the extension of the SDAS alone will not address the issue. Genetics must be identified to enhance beef traits without undermining advances in dairy breeding.

Establishing a national DNA calf registration strategy needs to be explored. It would require the genotyping of the cow herd. With setup costs in the region of €40m and annual costs of €28m, it is not cheap. The dividends to dairy and beef farmers would have to be established. There would also have to be recognition across all stakeholders that the dividends would extend beyond the farm gate and therefore so should the investment required.

To date, the investment focus associated with abolition of quota has been on increased processing capacity and the direct costs associated with herd expansion. It is time to broaden this to make sure all parts of the jigsaw are in place. The dairy sector has real skin in the game when it comes to ensuring beef-bred dairy calves do not become worthless. Those crossbreeding also need to accept that they may have to share some of the dividend from their breeding policy with the farmer that is prepared to take the bull calves through to beef.

Trade: deal on unfair trading a step in right direction

European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan.

After an intense period of negotiations between the EU institutions, white smoke has emerged on a deal on Unfair Trading Practices (UTP).

This was an attempt, led by European Commissioner for Agriculture Phil Hogan, to try to rebalance the power in the food chain – where we have a scenario that sees farmers having the lowest share of the value despite having most of the work, while retail takes half the value for a cash sale business and a short time on the shelf.

Securing support across the EU was quite a challenge and critics of the deal maintain that the measures under the UTP are so diluted that they are meaningless from a farmer’s perspective. While it is true farmers would want more, the widespread opposition to the Commissioner’s initiative from supermarket representatives would indicate that the UTPs will play some role in rebalancing the supply chain.

Rather than condemn for not going far enough, this is a case of where it was better to light a candle than curse the dark. The UTP legislation may be more modest than farmers might want but it is the most that can be achieved at this point. We should welcome it as a worthy first step and seek to build on it.

Trimming: Creed agrees to publish names of factories for over-trimming

Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed.

Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed has agreed with the IFA to publish the names of meat factories fined for over-trimming carcases in 2017.

Farmer attention will focus on these plants. However, the bigger picture is that in agreeing to publish the names, the minister has taken the first step in delivering improved transparency.

The next steps involve putting a robust oversight policy in place. Recently, Commissioner Hogan told farmers that technology exists for farms to be photographed by satellite three times per week. It is not tenable to say that the necessary technology is not available to allow farmers to view their carcases prior to grading and weighing. Factories have an opportunity to demonstrate a real commitment to transparency.

This should extend beyond beef into sheep. Farmers have reacted angrily to the refusal by Irish Country Meats to provide details on clipping charges and the imposition of these clipping charges on all farmers.

Vet dispute: farmers cannot be used as pawns

As we report in our front page story this week, a dispute between the Department of Agriculture and Veterinary Ireland is starting to cause disruption to the flow of animals through abattoirs.

It appears that Veterinary Ireland, representing private vets who provide inspection services within abattoirs for the Department, has escalated a long-running dispute at a time to cause maximum disruption, at one of the busiest slaughtering periods across the various sectors.

Regardless of the issues, both parties cannot allow farmers to be caught in the crossfire and used as pawns in the negotiations.

Private vets have a huge responsibility to these farmers, depending on them for the primary source of income, while the Department has a clear responsibility to ensure the provision of adequate services to allow for proper functioning of the sector. We expect to see a speedy resolution.

Season’s greetings: Happy Christmas

The team in the Irish Farmers Journal would like to thank you all for your support through the year and wish you and your families a safe and enjoyable Christmas. We will be out next Thursday as normal with daily updates on farmersjournal.ie.

SHARING OPTIONS