The term economic resilience crops up again and again in the context of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and Ireland Inc is very lucky to have a huge domestically-owned and operated sector like agri food that is so important to its economy.

The agri food sector accounts for almost 20% of Irish economic activity and expenditure and, as the chart below shows, provides almost five times the level of Irish economic activity as the pharma sector, the next highest spending sector (CSO/DEBE/FDII).

The Irish agri food sector has strong resilience credentials, but equally clearly needs supports and some joined-up thinking.

The huge uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is leading to a lot of re-imagining of economies and economic supply chains.

This re-imagining and resetting is appropriate in the sense that the COVID-19 pandemic in its overall economic impact is unique and, in many respects, the equivalent to an economic depression, a currency shock and a food demand shock event all at once.

The pandemic has led to a huge amount of contemplation as to what might work in very complex two- and three-speed post-lockdown economies.

Food service demand

For the broad agri food sector in Ireland, which exports 80% to 90% of production, the key factor immediately as lockdown is eased will be the pace of the pick-up in food service demand across European and international markets.

A lot will be revealed in the next four to six weeks and the pace of the re-emergence of demand will dictate the likely need for additional EU supports, including improved private storage aid and direct payment supplements, along with the institution of a national State-backed credit scheme which has now been signalled for the UK, as well as every country in the EU except Ireland.

The emergence of larger-scale home delivery options for grocery and food service could significantly change the dynamics of the sector

In the medium term, the emergence of larger-scale home delivery options for grocery and food service could significantly change the dynamics of the sector, hopefully improving cost recovery through improved price, through the creation of a significant alternative buying platform to supermarket dominance.

This is not just due to the emergence of a competing demand channel, but the fact that neither restaurants nor food service sell below cost and so the growth of this new platform might finally kill off predatory pricing of fresh food products which has beggared the production and processing of food over the last 20 years in Ireland and across the EU.

Climate change policy must be linked to food prices

In Ireland, for the moment, there remains a fixation with the wish to impose climate change constraints on our agri food production systems regardless of the real scientific or economic impact, or the huge chasm that exists between the regulatory costs associated with a new green deal or a more accelerated national emissions target and the recovery of even a small percentage of these costs in supermarket-dominated food pricing.

The total and utter separation of food production costs from food pricing economically, politically and scientifically is one of the major disconnects in Irish and EU discourse in regard to incomes in agriculture and, increasingly, climate change policies.

While Government departments talk about regulation and consumer choice being aligned, the only market signal from the supermarket-dominated grocery business is - next year cheaper again!

If we look at best practice, how climate change restructuring was managed for the energy sector or even the auto industry, the new climate change policies for agriculture should involve a balancing of new regulations and new business risks with a commitment to enabling cost recovery.

This would be a welcome contrast to what passes for debate on the evolution of agri business, our largest business sector in recent years.

Chronic impact

Instead of a recognition of the chronic impact of 20 years of below-cost selling and loss leading of fresh foods, we get pantomimed versions of debates that sets producers against processors and processors against climate activists and animal welfare gurus.

What the poor voters/consumers get is a lot of heat and no light shone.

Nowhere in the debate about sustainable food production and climate change is there yet a recognition, as with renewable energy, that specific price supports plus a ban on below-cost selling are a must if low-carbon systems are to be delivered and fostered.

Nowhere is there a supportive tax incentive scheme that favours the introduction of lower carbon options such as with electric cars.

A changing dynamic in consumer purchases post-COVID-19 may provide the only cause for hope

So in the absence of an enlightened approach to the agri food sector, a changing dynamic in consumer purchases post-COVID-19 may provide the only cause for hope.

In the analysis of post-lockdown economies, huge concerns have emerged about the future of high street retail.

This is because the broad non-food retail sector was struggling hugely with competition from online competitors and the huge cost of legacy-based high business rental.

Pre-pandemic, out-of-home purchasing of grocery food as distinct from food service (restaurants, bars, cafés) had established a small but not insignificant share of food consumption, running at about 6% of grocery shopping in the USA and around 3% to 4% in the UK and Ireland.

While still not huge, the home grocery sector was growing significantly and between 2015 and 2019 had shown an annual growth rate of 15% per year.

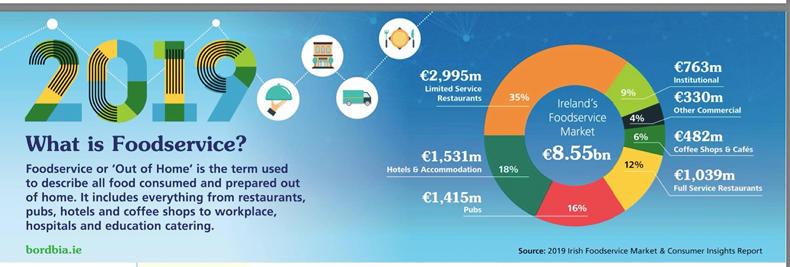

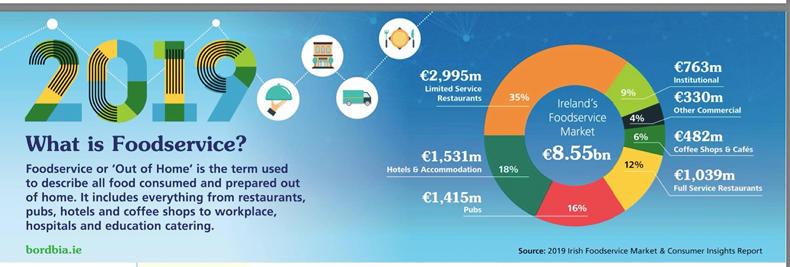

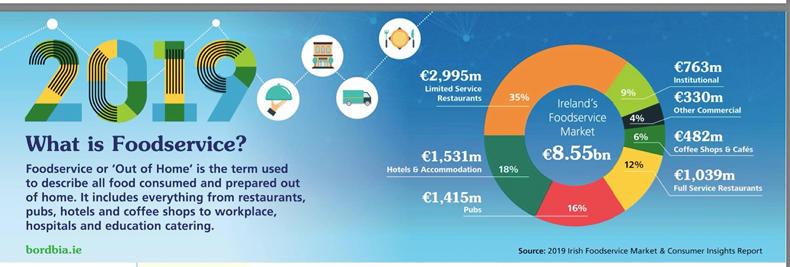

In most EU countries, food consumed in restaurants, cafés, bars and takeaways (food service) represents about 40% of food consumption versus 60% through grocery retail (Kantar, Eurostat). In Ireland, the mix is nearer to 35% food service versus 65% grocery (CSO).

Figures from Kantar and the FT show that grocery home deliveries have increased by up to 22% in the US and UK over the lockdown period.

Analyses of business risk, focused on the big four supermarkets in the UK from 2016 to 2018, showed that concern about online competitors was only second to concern about the increased market share of the discounters, with concerns about supply chain resilience post-Brexit coming in third.

Penny drops

So while waiting for the penny to drop with regulators, climate change activists and global trade promoters that increased regulation means higher cost, it will be interesting to see whether a more rational market structure that links consumer demand for sustainable production might be reflected in food pricing under a more diverse route to market outcome.

It would indeed be ironic if because neither food service outlets or restaurants nor grocery home deliveries sell below cost, a broadening of this market outlet helps to reset the proper functioning of food markets and, in particular, link sustainable food production to food prices.

Read more

New government must embrace Irish agriculture

Food-to-go sales collapse 70% for Greencore since COVID-19 lockdown

The term economic resilience crops up again and again in the context of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and Ireland Inc is very lucky to have a huge domestically-owned and operated sector like agri food that is so important to its economy.

The agri food sector accounts for almost 20% of Irish economic activity and expenditure and, as the chart below shows, provides almost five times the level of Irish economic activity as the pharma sector, the next highest spending sector (CSO/DEBE/FDII).

The Irish agri food sector has strong resilience credentials, but equally clearly needs supports and some joined-up thinking.

The huge uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is leading to a lot of re-imagining of economies and economic supply chains.

This re-imagining and resetting is appropriate in the sense that the COVID-19 pandemic in its overall economic impact is unique and, in many respects, the equivalent to an economic depression, a currency shock and a food demand shock event all at once.

The pandemic has led to a huge amount of contemplation as to what might work in very complex two- and three-speed post-lockdown economies.

Food service demand

For the broad agri food sector in Ireland, which exports 80% to 90% of production, the key factor immediately as lockdown is eased will be the pace of the pick-up in food service demand across European and international markets.

A lot will be revealed in the next four to six weeks and the pace of the re-emergence of demand will dictate the likely need for additional EU supports, including improved private storage aid and direct payment supplements, along with the institution of a national State-backed credit scheme which has now been signalled for the UK, as well as every country in the EU except Ireland.

The emergence of larger-scale home delivery options for grocery and food service could significantly change the dynamics of the sector

In the medium term, the emergence of larger-scale home delivery options for grocery and food service could significantly change the dynamics of the sector, hopefully improving cost recovery through improved price, through the creation of a significant alternative buying platform to supermarket dominance.

This is not just due to the emergence of a competing demand channel, but the fact that neither restaurants nor food service sell below cost and so the growth of this new platform might finally kill off predatory pricing of fresh food products which has beggared the production and processing of food over the last 20 years in Ireland and across the EU.

Climate change policy must be linked to food prices

In Ireland, for the moment, there remains a fixation with the wish to impose climate change constraints on our agri food production systems regardless of the real scientific or economic impact, or the huge chasm that exists between the regulatory costs associated with a new green deal or a more accelerated national emissions target and the recovery of even a small percentage of these costs in supermarket-dominated food pricing.

The total and utter separation of food production costs from food pricing economically, politically and scientifically is one of the major disconnects in Irish and EU discourse in regard to incomes in agriculture and, increasingly, climate change policies.

While Government departments talk about regulation and consumer choice being aligned, the only market signal from the supermarket-dominated grocery business is - next year cheaper again!

If we look at best practice, how climate change restructuring was managed for the energy sector or even the auto industry, the new climate change policies for agriculture should involve a balancing of new regulations and new business risks with a commitment to enabling cost recovery.

This would be a welcome contrast to what passes for debate on the evolution of agri business, our largest business sector in recent years.

Chronic impact

Instead of a recognition of the chronic impact of 20 years of below-cost selling and loss leading of fresh foods, we get pantomimed versions of debates that sets producers against processors and processors against climate activists and animal welfare gurus.

What the poor voters/consumers get is a lot of heat and no light shone.

Nowhere in the debate about sustainable food production and climate change is there yet a recognition, as with renewable energy, that specific price supports plus a ban on below-cost selling are a must if low-carbon systems are to be delivered and fostered.

Nowhere is there a supportive tax incentive scheme that favours the introduction of lower carbon options such as with electric cars.

A changing dynamic in consumer purchases post-COVID-19 may provide the only cause for hope

So in the absence of an enlightened approach to the agri food sector, a changing dynamic in consumer purchases post-COVID-19 may provide the only cause for hope.

In the analysis of post-lockdown economies, huge concerns have emerged about the future of high street retail.

This is because the broad non-food retail sector was struggling hugely with competition from online competitors and the huge cost of legacy-based high business rental.

Pre-pandemic, out-of-home purchasing of grocery food as distinct from food service (restaurants, bars, cafés) had established a small but not insignificant share of food consumption, running at about 6% of grocery shopping in the USA and around 3% to 4% in the UK and Ireland.

While still not huge, the home grocery sector was growing significantly and between 2015 and 2019 had shown an annual growth rate of 15% per year.

In most EU countries, food consumed in restaurants, cafés, bars and takeaways (food service) represents about 40% of food consumption versus 60% through grocery retail (Kantar, Eurostat). In Ireland, the mix is nearer to 35% food service versus 65% grocery (CSO).

Figures from Kantar and the FT show that grocery home deliveries have increased by up to 22% in the US and UK over the lockdown period.

Analyses of business risk, focused on the big four supermarkets in the UK from 2016 to 2018, showed that concern about online competitors was only second to concern about the increased market share of the discounters, with concerns about supply chain resilience post-Brexit coming in third.

Penny drops

So while waiting for the penny to drop with regulators, climate change activists and global trade promoters that increased regulation means higher cost, it will be interesting to see whether a more rational market structure that links consumer demand for sustainable production might be reflected in food pricing under a more diverse route to market outcome.

It would indeed be ironic if because neither food service outlets or restaurants nor grocery home deliveries sell below cost, a broadening of this market outlet helps to reset the proper functioning of food markets and, in particular, link sustainable food production to food prices.

Read more

New government must embrace Irish agriculture

Food-to-go sales collapse 70% for Greencore since COVID-19 lockdown

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: