With the harvest almost upon us, many growers are finding strange grass weeds emerging from their previously clean crops.

It is very important that these (1) be identified prior to harvest and (2) be classified as to their state of resistance for future control.

Most serious tillage farmers will be acutely aware of the growing problem of grass weeds and their implication and cost for crop production.

Fewer will be aware of the consequences of even lower numbers for producers of certified seed.

The Irish seed industry has set itself higher standards for grass weed seed contamination and this is effectively zero-tolerance for the crop in the field and the seed in the bag.

Zero-tolerance

The seed trade (ISTA) has opted for zero-tolerance for a number of grass weeds such as wild oats, sterile brome and black grass and commercial growers have also become acutely aware of the importance of this.

Imported seed, especially from Britain, always poses a risk of contamination but imported grain to be planted as seed will represent an even higher risk.

Irish growers are now realising this fact, but it seems to be a bit too late in some instances as infestation is already present.

When any of these grasses get into fields destined for seed production, the consequences can be complete loss of the crop for certification.

This has implication for the seed producer but also for the seed customer as this seed will not be available.

So it is hardly surprising that the seed trade (ISTA) has been actively involved in part-funding a Teagasc research project to assess the current state of resistance or susceptibility to different herbicide families in a range of serious grass weeds.

Findings

Early findings from this work was presented at the Teagasc Tillage Conference last spring. An interim report was published in Teagasc’s recent T-Research magazine (Volume 12: Number 2).

The presence of resistance to herbicides will either alter the control strategy that must be used while increasing its cost or it could make control either difficult or impossible using herbicides. This could be critical for certified seed production.

The main face of the project is PhD student Ronan Byrne.

However, other Teagasc people are also involved including John Spink, Susanne Barth and Tim O’Donovan, now with Seedtech. The report authors define herbicide resistance as “the evolved ability of a plant to survive a dose of herbicide that would normally be lethal to it”.

Given the increasing reports of the presence of resistance in our grass weeds, it is hardly surprising that there is research to help understanding the nature of this resistance.

Sample collection

Grass weed samples were taken initially from fields where weed control proved difficult in 2016.

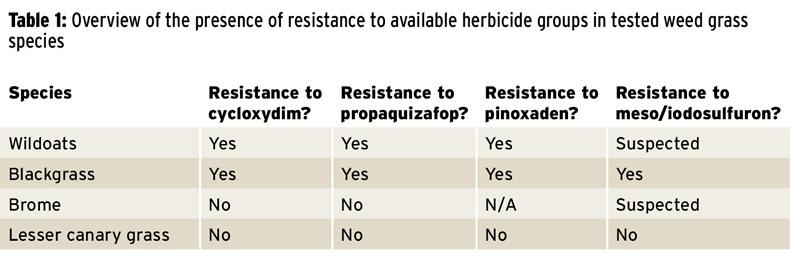

The specific grass weeds being examined were wild oats, blackgrass, lesser canary grass and various species of brome.

In that year, 77 different populations of grass weeds were tested for their susceptibility to four different commonly used herbicide actives.

The total population was made up of wild oats (31), brome (22), blackgrass (16) and lesser canary grass (8).

The different weed populations were then tested for their susceptibility, or otherwise, to pinoxaden (Axial), cycloxydim (Stratos Ultra), propaquizafop (Falcon) and meso/iodosulfuron (Pacifica), representing the ACCase- and ALS-inhibiting herbicides.

The active efficacy or level of resistance was measured as the difference between the biomass of plants sprayed with the various herbicides and that of unsprayed controls.

A resistance score was calculated by dividing the weight of the biomass of the sprayed plant by that of the unsprayed control.

This provided a resistance score for each population to each active ingredient tested. This survey is being continued in 2017 and 2018.

Resistance found

While it is too early to make absolute statements about the level or incidence of resistance, the findings of this research to date indicate that ‘dim’, ‘den’, ‘fop’ and sulfonylurea resistance seem to be present in wild oats.

Similar findings were achieved for blackgrass.

Tests on the populations of brome grasses indicated no signs of resistance to ACCase inhibitors, but resistance is suspected to ALS inhibitors (sulfonylureas).

Results

Implications

While not all samples showed resistance, the results add complexity for the tillage sector.

The authors indicate that, while resistance occured initially as a mutation, its spread is most likely through the spread of resistant seeds.

This means that the potential for the spread of resistance is significant.

It also points to the need for much greater biosecurity between fields and farms to help prevent this spread and it may cause input costs to rise and result in reduced profit margins for growers.

The next steps

While resistance is present, the researchers now aim to test the rate responsiveness of the different actives on the different populations.

There are also plans to attempt to check the origin of recent blackgrass outbreaks in this country but it may be much more difficult to confirm the exact source of infestation.

However, it may be possible to age the mutation levels in resistant Irish populations and thus indicate the possible period of introduction.

It would also be good to know if fields with blackgrass present are entirely made up of resistant types or if populations contain a mixture of susceptible types and types with resistance to different active families.

However, even if there were susceptible types present, resistant types would quickly predominate.

Farm level response to infestation with any of these grasses must be definite and instant.

These weeds must not be tolerated in our fields because control cost is only eating into margins and we know that many of these grasses will overcome the efficacy of herbicides over time to leave us with an even bigger problem if we allow them to proliferate in the meantime.

So zero-tolerance is the only sustainable option.

SHARING OPTIONS