The defining feature of Irish life in 2020 has been an appreciable increase in volatility.

That volatility has emerged in the form of political instability following the conclusion of the general election, economic uncertainty on account of the global health pandemic and, in the case of the agricultural community, additional meteorological volatility.

Despite record rainfall totals during the month of February and the subsequent flooding crisis, a little over two months have passed and already there is a sense of anxiety developing among many farmers in the midlands, east and northeast of the country about the spectre of an acute fodder shortage emerging through the months of June and July, on account of the current settled spell weather.

Below-average rainfall

Precipitation totals across a significant portion of the country have been well below average for the months of April and May, with accumulated rainfall totals reaching just 19% to 25% of average levels in the areas surrounding Dublin, the midlands and the northeast.

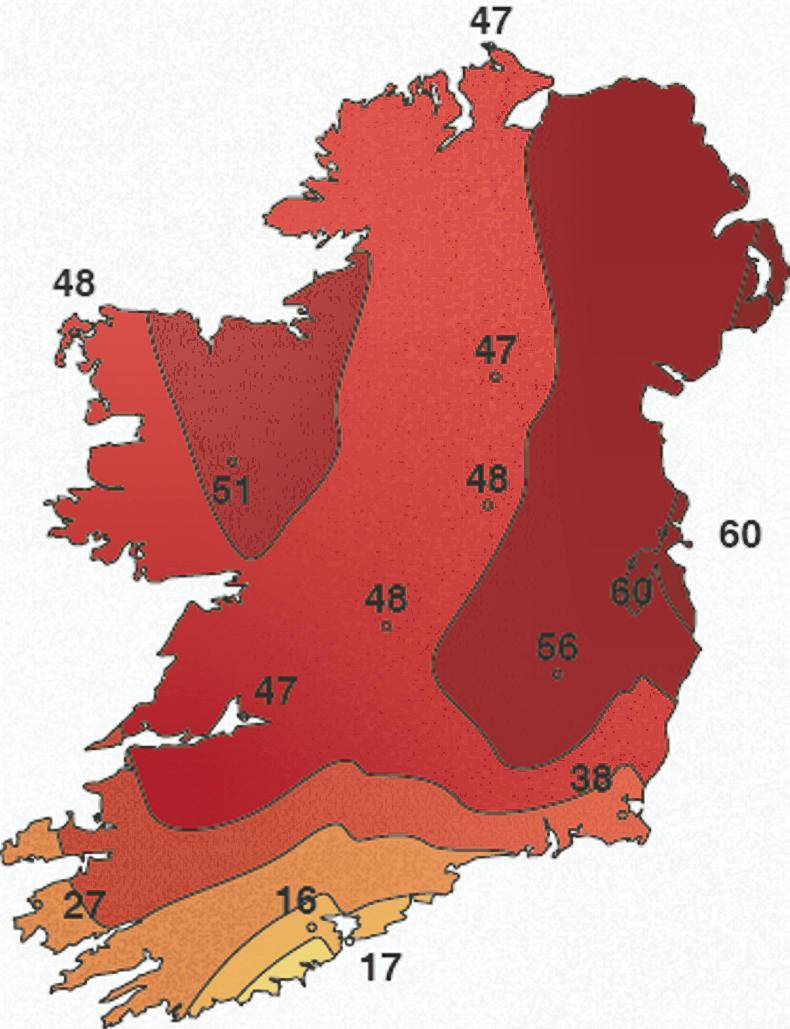

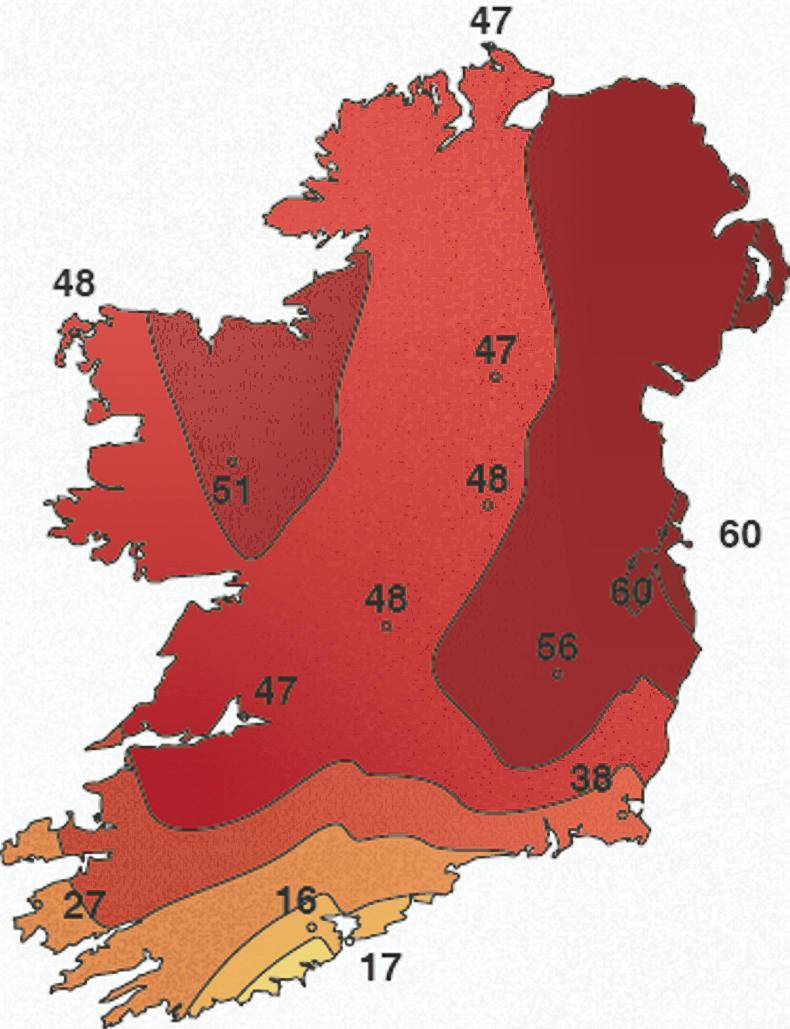

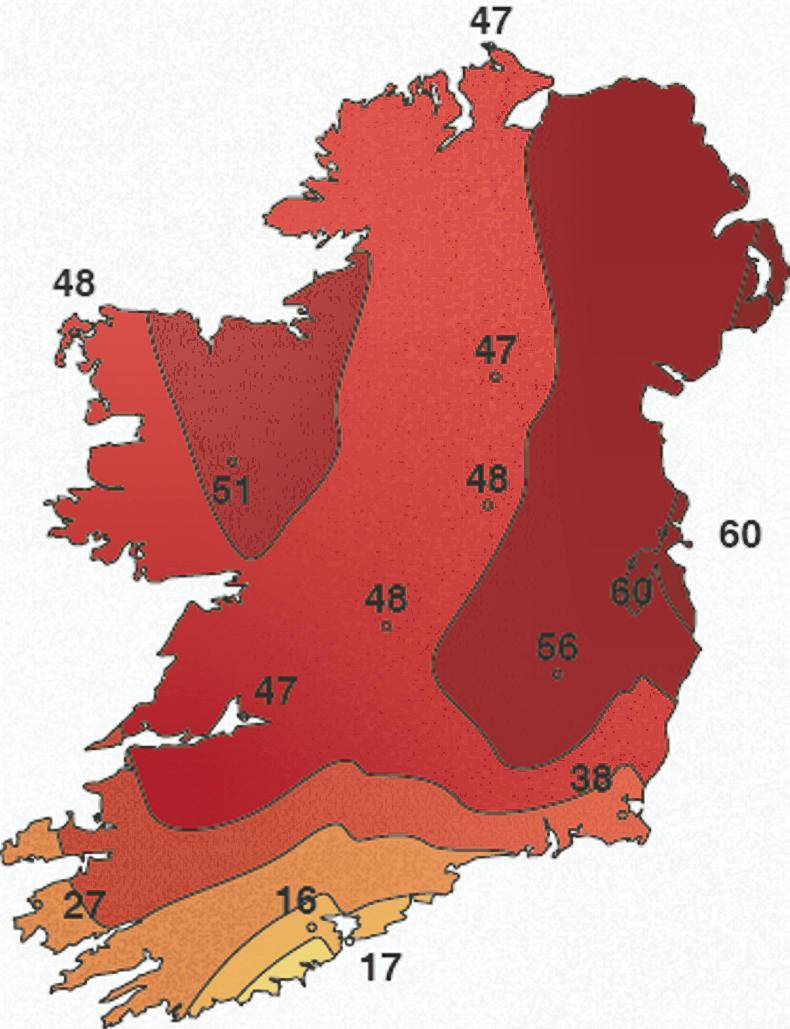

Soil moisture deficits, too, are already exceeding the crucial 30mm band in over two-thirds of the country, with the exception being in parts of south Munster.

Nationwide soil moisture deficits on Wednesday 13 May 2020.

Meanwhile, with little or no rain forecast for the immediate seven- to 10-day period, it appears likely that Ireland will enter a late spring drought by the end of this week.

Indeed, projections for the week 18 to 24 May indicate that soil moisture deficits in the midlands, east and northeast may well exceed 60mm to 80mm in all soil types, though still below those observed during the 2018 drought.

Ireland’s climate is defined as being temperate oceanic, according to the Koppen climate classification, devised by German botanist Wladimir Koppen in 1918.

As such, drought is considered to be a relatively rare occurrence in a country which records between 750mm and 2,800mm of rainfall per year.

Complex picture

However, if we examine the past climate of Ireland since the 1750s, a rather different and more complex picture emerges.

A research paper by Wilby et al 2016 concluded that between 1850 and 2015, a total of 45 drought events occurred, excluding the drought of 2018.

This equates to a drought occurring on the island of Ireland once every 3.6 years, which further demonstrates that Ireland, despite its rather temperate climate, is exposed to the risks posed by the presence of drought, perhaps far more so than we typically assume it to be.

While the average of a drought every 3.6 years seems particularly short, it gives a false perception as to the actual frequency of drought on the island of Ireland.

The true frequency of drought in Ireland is far more complex

As is often the case with climate, the true frequency of drought in Ireland is far more complex, with the majority of drought events occurring during drought-rich periods.

Seven of these were identified by S Noone et al in their 2017 paper, which developed a drought catalogue for Ireland.

The seven drought rich periods identified occurred from 1854-1860, 1884-1896, 1904-1912, 1921-1924, 1932-1935, 1952-1954 and 1969-1977 and have been caused by natural variability in the Earth's climate.

Implications for farming

With the significant drought of 2018 still fresh in the minds of many, one may begin to question whether we too are entering another drought-rich period and, if so, what are the immediate implications for the farming community?

Like the frequency of drought conditions in Ireland, past fodder crises have also occurred rather more frequently than previously envisaged.

As part of my ongoing PhD thesis in association with UCC and the EPA, I have derived preliminary results using historical accounts, past meteorological data, mortality rates and fodder price records, which indicate that between 1514 and 2019, there were 91 fodder crises of varying magnitudes recorded on the island of Ireland.

Subsequent shortages of fodder have led to significant financial and livestock losses, and, in previous centuries, resulted in pestilence, disease and malnutrition of livestock and the general public.

Meanwhile, present-day anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change is already leaving its fingermarks upon the Irish agroclimatic landscape, with increased fodder crises likely on account of increasingly volatile climatic conditions over the coming century.

The next two to four weeks will be crucial in determining if Mother Nature decides to flatten the curve

This increase in the occurrence of fodder crisis is based on present agricultural practices, and is in spite of projections by Professor Paul Nolan in 2015, which indicated the number of grass growth days will increase by up to 43 days per year in a medium emission scenario by mid-century.

Instead, changes in the position of the jet stream, Atlantic storm track, increasing temperature and evapotranspiration rates and the prevalence of persistent anticyclonic blocking patterns will lead to summer droughts like 2018 becoming more frequent, and regionally acute, by mid-century, though not annual events.

In the meantime, the next two to four weeks will be crucial in determining if Mother Nature decides to flatten the curve of our increasing soil moisture deficits or whether we in the agricultural community must prepare for the new normal of winter flooding followed by summer droughts.

References: P. Nolan 2015, R. L. Wilby 2016, S. Noone 2017

Read more

Pig plant hit with virus outbreak

Beef taskforce: Grant Thornton cites 'unanticipated challenges'

Weather conditions balanced on a knife edge

The defining feature of Irish life in 2020 has been an appreciable increase in volatility.

That volatility has emerged in the form of political instability following the conclusion of the general election, economic uncertainty on account of the global health pandemic and, in the case of the agricultural community, additional meteorological volatility.

Despite record rainfall totals during the month of February and the subsequent flooding crisis, a little over two months have passed and already there is a sense of anxiety developing among many farmers in the midlands, east and northeast of the country about the spectre of an acute fodder shortage emerging through the months of June and July, on account of the current settled spell weather.

Below-average rainfall

Precipitation totals across a significant portion of the country have been well below average for the months of April and May, with accumulated rainfall totals reaching just 19% to 25% of average levels in the areas surrounding Dublin, the midlands and the northeast.

Soil moisture deficits, too, are already exceeding the crucial 30mm band in over two-thirds of the country, with the exception being in parts of south Munster.

Nationwide soil moisture deficits on Wednesday 13 May 2020.

Meanwhile, with little or no rain forecast for the immediate seven- to 10-day period, it appears likely that Ireland will enter a late spring drought by the end of this week.

Indeed, projections for the week 18 to 24 May indicate that soil moisture deficits in the midlands, east and northeast may well exceed 60mm to 80mm in all soil types, though still below those observed during the 2018 drought.

Ireland’s climate is defined as being temperate oceanic, according to the Koppen climate classification, devised by German botanist Wladimir Koppen in 1918.

As such, drought is considered to be a relatively rare occurrence in a country which records between 750mm and 2,800mm of rainfall per year.

Complex picture

However, if we examine the past climate of Ireland since the 1750s, a rather different and more complex picture emerges.

A research paper by Wilby et al 2016 concluded that between 1850 and 2015, a total of 45 drought events occurred, excluding the drought of 2018.

This equates to a drought occurring on the island of Ireland once every 3.6 years, which further demonstrates that Ireland, despite its rather temperate climate, is exposed to the risks posed by the presence of drought, perhaps far more so than we typically assume it to be.

While the average of a drought every 3.6 years seems particularly short, it gives a false perception as to the actual frequency of drought on the island of Ireland.

The true frequency of drought in Ireland is far more complex

As is often the case with climate, the true frequency of drought in Ireland is far more complex, with the majority of drought events occurring during drought-rich periods.

Seven of these were identified by S Noone et al in their 2017 paper, which developed a drought catalogue for Ireland.

The seven drought rich periods identified occurred from 1854-1860, 1884-1896, 1904-1912, 1921-1924, 1932-1935, 1952-1954 and 1969-1977 and have been caused by natural variability in the Earth's climate.

Implications for farming

With the significant drought of 2018 still fresh in the minds of many, one may begin to question whether we too are entering another drought-rich period and, if so, what are the immediate implications for the farming community?

Like the frequency of drought conditions in Ireland, past fodder crises have also occurred rather more frequently than previously envisaged.

As part of my ongoing PhD thesis in association with UCC and the EPA, I have derived preliminary results using historical accounts, past meteorological data, mortality rates and fodder price records, which indicate that between 1514 and 2019, there were 91 fodder crises of varying magnitudes recorded on the island of Ireland.

Subsequent shortages of fodder have led to significant financial and livestock losses, and, in previous centuries, resulted in pestilence, disease and malnutrition of livestock and the general public.

Meanwhile, present-day anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change is already leaving its fingermarks upon the Irish agroclimatic landscape, with increased fodder crises likely on account of increasingly volatile climatic conditions over the coming century.

The next two to four weeks will be crucial in determining if Mother Nature decides to flatten the curve

This increase in the occurrence of fodder crisis is based on present agricultural practices, and is in spite of projections by Professor Paul Nolan in 2015, which indicated the number of grass growth days will increase by up to 43 days per year in a medium emission scenario by mid-century.

Instead, changes in the position of the jet stream, Atlantic storm track, increasing temperature and evapotranspiration rates and the prevalence of persistent anticyclonic blocking patterns will lead to summer droughts like 2018 becoming more frequent, and regionally acute, by mid-century, though not annual events.

In the meantime, the next two to four weeks will be crucial in determining if Mother Nature decides to flatten the curve of our increasing soil moisture deficits or whether we in the agricultural community must prepare for the new normal of winter flooding followed by summer droughts.

References: P. Nolan 2015, R. L. Wilby 2016, S. Noone 2017

Read more

Pig plant hit with virus outbreak

Beef taskforce: Grant Thornton cites 'unanticipated challenges'

Weather conditions balanced on a knife edge

SHARING OPTIONS