The name Parkes in New South Wales (NSW) in Australia may appear vaguely familiar to some Irish Farmers Journal readers.

That is because we carry occasional contributions from a farmer there called Bruce Watson.

When the Irish Tillage and Land Use Society (ITLUS) visited Australia in January 2020, one of the farms on our itinerary was Kebby and Watson Farm, which is run by partners Bruce Watson and his brother-in-law Mark Swift.

Soil being eroded by a recent storm. The soil had been moved from the field on the left of the fence line. It piled higher by the fence as the wind speed was lowered and it was spread all across the field to the right, even where the stubble is very visible.

Bruce, whom I had met in Ireland years previously, was away when we visited, so his brother-in-law kindly showed us around the local area, as well as the farm itself.

Mark told us that Parkes itself is not regarded as an agricultural town, but rather a mining town, which also provides a range of government services.

Mark told us that the survival of the town hinged on proximity of the railroad from Melbourne to Brisbane. The town now has a freight business facility adjacent to the railroad which services both the agricultural and mining sectors in the region.

The farm history

Farms in the area are generally greater than 3,000ha in size and the Kebby and Watson farm, which has been on the go since 1902, is now 3,800ha (9,390ac).

It was initially a grazing farm, but the crop area increased over time as crop performance became more reliable.

The 2-3cm of soil on the top of this profile blew in during a storm and covered the organic residue that had been left on top in this field to help protect it.

The last of the livestock on the farm finished in 2001 and it was only after that that the owners realised how much of a help the animals had been for the crops on the farm.

“You lose less with livestock in short droughts,” Mark stated.

Initial cropping involved a cereal-to-cereal rotation, but they observed that crop performance declined after a few years.

Chaff is gathered into rows and placed in the combine wheel tracks to be burned when it is safe to do so.

Realising the need for other crops and a rotation, canola (oilseed rape) was introduced from 2006.

Pulses were added in the last decade and they quickly showed a yield advantage to the following crop.

However, pulses are very fussy and highly influenced by the weather the year brings, Mark commented.

Summer cropping and rotations

Initially all crops were sown in their autumn because they could cope better with climate. However, the farm moved to some summer cropping (spring-sown crops) in the last decade, specifically mung beans and sorghum.

Both were good in the initial years, but in 2012 there was no rain from sowing to 28 February, which resulted in poor crops and a hard landing for the concept of summer cropping.

However, Mark said that they stayed with summer crops and had some good and poor years since then.

A sample of the mung beans grown in 2019.

While yield is a real factor, so is the benefit of the reduction in general stress levels associated with the whole farming system.

As time went by, they worked more with rotations and began to use double brakes, ie two non-cereal crops in succession.

This made a big difference to yield and also to water use efficiency. Indeed, it helped to make the farm profitable again, Mark stated.

Water and yield

Mark said the typical good yields in this rain-fed region would be around 4t/ha for wheat and 2t/ha for canola.

However, yields would drop by at least 0.5t/ha when crops would be challenged by weather events such as drought.

“It's all about water use efficiency,” Mark commented.

This influences decisions that range from planting date to herbicide strategy to the input level used.

They can expect to get a few summer storms, but this rainfall is not guaranteed. And if it rains, then there is an increased need to tackle the weeds that will emerge.

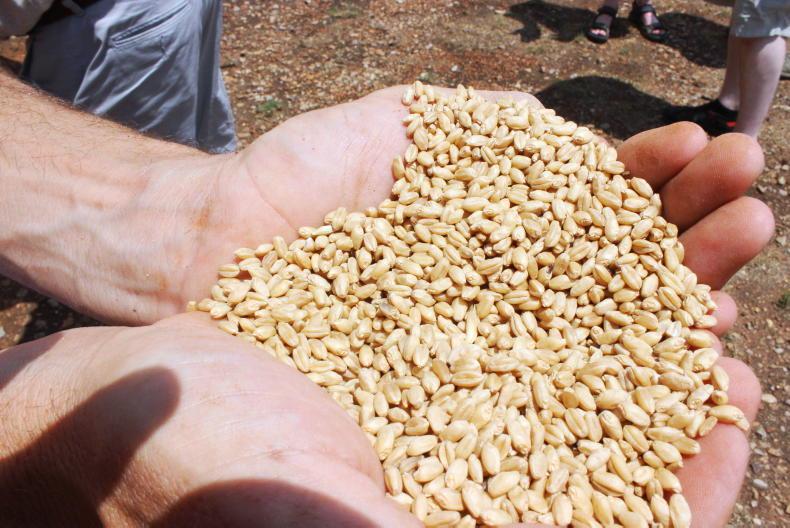

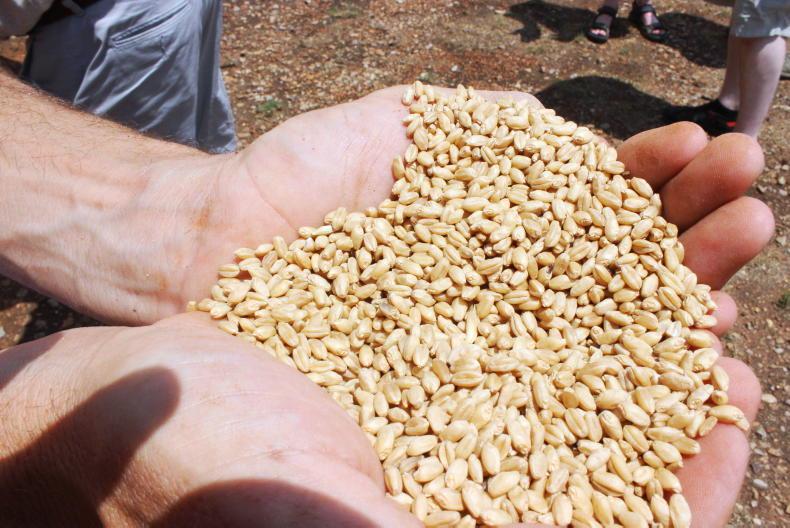

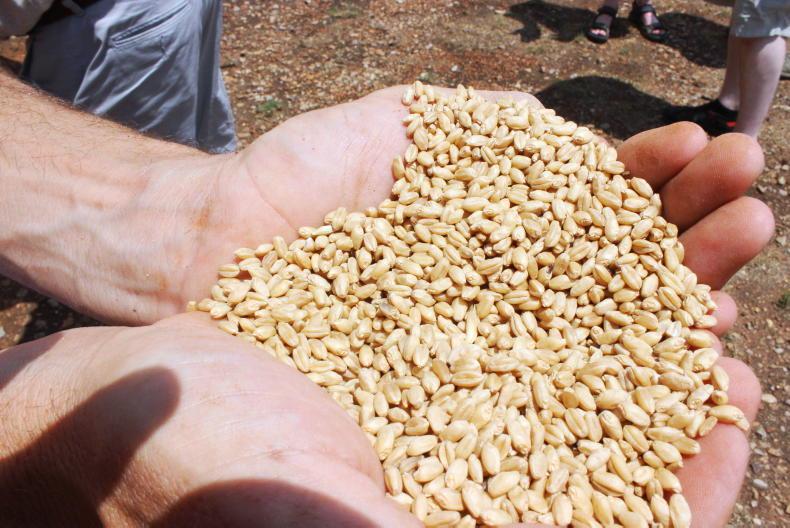

A sample of the wheat grown in 2019 which did not show the signs of the bad drought.

Rainfall in the region can range from 400mm to 800mm per year, but it is highly variable.

In 2018 and 2019 combined, the total rainfall was 500mm, leaving soil reserves very low.

In an effort to help utilise all available water, the farm is accessing a water assessment service.

This involves renting probes that assess soil moisture levels to below one metre depth and access to a professional service to interpret and advise on these results.

Knowing the water-holding capacity of all paddocks helped to better target nutrients and all other inputs efficiently.

Municipal sludge

The farm is also now using municipal sludge from one of the major cities in an effort to improve soil organic matter and to improve the moisture-holding capacity of its soils.

This is normally applied at 25t/ha ahead of a canola crop and they have the capacity to store about 50,000t on the farm ahead of the periods of peak demand.

The sludge is seen as a cheap source of nitrogen and phosphorus, but its application is seen as the biggest challenge.

Bins for storing legumes at the Kebby & Watson farm.

It would not be applied ahead of cereal crops. Mark commented that he would like to be able to inject it into the ground, but this would require additional water to make the sludge sufficiently fluid for injecting.

Sludge use is adding to farm production, while also providing good value nutrients.

While the summer cropping does not particularly like the red soils on the farm, because they get too hot, the improved structure in the soils is enabling better water percolation into the soil profile to enhance reserves for future cropping.

Climate is harsh

While water is always a concern (too little and too much), frost and excessive heat around flowering time can also seriously dent the potential of any crop.

A crop of barley that was not harvested because it was not worth wearing out a combine for.

Temperatures can fluctuate massively between day and night and frost is a real risk at times. Frost before and during flowering can cause the loss of a large number of grain sites in every head.

Air temperatures can get up into the high 40s Celsius in summer during the day and be below 5C on the following morning. That is harsh on crops.

Cropping calendar

Winter wheat is generally sown in the second and third week of April and harvested in the last week of November to the first week of December.

Early season decisions are the main ones which influence yield potential. “Wheat is a great compensater,” Mark stated, and so he reduced seeding rate to 100 seeds per square metre in the dry year in an effort to decrease cost in the face of limited yield potential.

At harvest, the bulk of the grain is delivered to the local bulk handling system operated by Landmark. Delivery costs $17 to $18/t, plus $1/t per month for storage. There is an additional cost of €6/t to €7/t for loading out.

Delivery from Parkes to the port is by train. Mark commented that the region needs a dedicated grain train system to help the efficiency of transport and delivery.

He noted that the system used for coal is only about one-fifth of the cost associated with the handling, transport and delivery of wheat. “It's all about organisation,” he stated.

Mechanisation

Equipment on the farm is well-considered and there did not appear to be surplus machine capacity. That said, there is some scope to do contracting work, specifically spraying and harvesting.

The wide wheel track on the Claas Xerion for the controlled traffic operation.

The farm operates a controlled traffic system, which minimises the tracks on the land. This is seen to be quite advantageous and will be continued into the future.

The planting system on the farm uses a very flexible Excel precision drill, which can very simply alter row widths when planting different crops.

This technology has also enabled the planting of crops between the stubble rows of the previous crop with the help of RTK autosteer technology.

Following crops are sown between the stubble rows of the previous crop with the help of controlled traffic and precision autosteer.

This means that new roots can follow in the channels of old roots and empty root channels can help with water percolation into the soil for future use.

Machines always follow in the same tracks and this is helping to minimise compaction on soil types that might be described as quite weak, due to their lack of organic matter and the basic loss of soil structure.

Kangaroos were easier to find when we got into the quieter countryside.

The 3,800ha are sown with a single drill, sprayed with a single self-propelled RoGator fitted with a Croplands sprayer and harvested with a single Case combine.

The spread of crops and planting and harvest dates helps to make this possible and the low level of machinery investment helps overall profitability.

The name Parkes in New South Wales (NSW) in Australia may appear vaguely familiar to some Irish Farmers Journal readers.

That is because we carry occasional contributions from a farmer there called Bruce Watson.

When the Irish Tillage and Land Use Society (ITLUS) visited Australia in January 2020, one of the farms on our itinerary was Kebby and Watson Farm, which is run by partners Bruce Watson and his brother-in-law Mark Swift.

Soil being eroded by a recent storm. The soil had been moved from the field on the left of the fence line. It piled higher by the fence as the wind speed was lowered and it was spread all across the field to the right, even where the stubble is very visible.

Bruce, whom I had met in Ireland years previously, was away when we visited, so his brother-in-law kindly showed us around the local area, as well as the farm itself.

Mark told us that Parkes itself is not regarded as an agricultural town, but rather a mining town, which also provides a range of government services.

Mark told us that the survival of the town hinged on proximity of the railroad from Melbourne to Brisbane. The town now has a freight business facility adjacent to the railroad which services both the agricultural and mining sectors in the region.

The farm history

Farms in the area are generally greater than 3,000ha in size and the Kebby and Watson farm, which has been on the go since 1902, is now 3,800ha (9,390ac).

It was initially a grazing farm, but the crop area increased over time as crop performance became more reliable.

The 2-3cm of soil on the top of this profile blew in during a storm and covered the organic residue that had been left on top in this field to help protect it.

The last of the livestock on the farm finished in 2001 and it was only after that that the owners realised how much of a help the animals had been for the crops on the farm.

“You lose less with livestock in short droughts,” Mark stated.

Initial cropping involved a cereal-to-cereal rotation, but they observed that crop performance declined after a few years.

Chaff is gathered into rows and placed in the combine wheel tracks to be burned when it is safe to do so.

Realising the need for other crops and a rotation, canola (oilseed rape) was introduced from 2006.

Pulses were added in the last decade and they quickly showed a yield advantage to the following crop.

However, pulses are very fussy and highly influenced by the weather the year brings, Mark commented.

Summer cropping and rotations

Initially all crops were sown in their autumn because they could cope better with climate. However, the farm moved to some summer cropping (spring-sown crops) in the last decade, specifically mung beans and sorghum.

Both were good in the initial years, but in 2012 there was no rain from sowing to 28 February, which resulted in poor crops and a hard landing for the concept of summer cropping.

However, Mark said that they stayed with summer crops and had some good and poor years since then.

A sample of the mung beans grown in 2019.

While yield is a real factor, so is the benefit of the reduction in general stress levels associated with the whole farming system.

As time went by, they worked more with rotations and began to use double brakes, ie two non-cereal crops in succession.

This made a big difference to yield and also to water use efficiency. Indeed, it helped to make the farm profitable again, Mark stated.

Water and yield

Mark said the typical good yields in this rain-fed region would be around 4t/ha for wheat and 2t/ha for canola.

However, yields would drop by at least 0.5t/ha when crops would be challenged by weather events such as drought.

“It's all about water use efficiency,” Mark commented.

This influences decisions that range from planting date to herbicide strategy to the input level used.

They can expect to get a few summer storms, but this rainfall is not guaranteed. And if it rains, then there is an increased need to tackle the weeds that will emerge.

A sample of the wheat grown in 2019 which did not show the signs of the bad drought.

Rainfall in the region can range from 400mm to 800mm per year, but it is highly variable.

In 2018 and 2019 combined, the total rainfall was 500mm, leaving soil reserves very low.

In an effort to help utilise all available water, the farm is accessing a water assessment service.

This involves renting probes that assess soil moisture levels to below one metre depth and access to a professional service to interpret and advise on these results.

Knowing the water-holding capacity of all paddocks helped to better target nutrients and all other inputs efficiently.

Municipal sludge

The farm is also now using municipal sludge from one of the major cities in an effort to improve soil organic matter and to improve the moisture-holding capacity of its soils.

This is normally applied at 25t/ha ahead of a canola crop and they have the capacity to store about 50,000t on the farm ahead of the periods of peak demand.

The sludge is seen as a cheap source of nitrogen and phosphorus, but its application is seen as the biggest challenge.

Bins for storing legumes at the Kebby & Watson farm.

It would not be applied ahead of cereal crops. Mark commented that he would like to be able to inject it into the ground, but this would require additional water to make the sludge sufficiently fluid for injecting.

Sludge use is adding to farm production, while also providing good value nutrients.

While the summer cropping does not particularly like the red soils on the farm, because they get too hot, the improved structure in the soils is enabling better water percolation into the soil profile to enhance reserves for future cropping.

Climate is harsh

While water is always a concern (too little and too much), frost and excessive heat around flowering time can also seriously dent the potential of any crop.

A crop of barley that was not harvested because it was not worth wearing out a combine for.

Temperatures can fluctuate massively between day and night and frost is a real risk at times. Frost before and during flowering can cause the loss of a large number of grain sites in every head.

Air temperatures can get up into the high 40s Celsius in summer during the day and be below 5C on the following morning. That is harsh on crops.

Cropping calendar

Winter wheat is generally sown in the second and third week of April and harvested in the last week of November to the first week of December.

Early season decisions are the main ones which influence yield potential. “Wheat is a great compensater,” Mark stated, and so he reduced seeding rate to 100 seeds per square metre in the dry year in an effort to decrease cost in the face of limited yield potential.

At harvest, the bulk of the grain is delivered to the local bulk handling system operated by Landmark. Delivery costs $17 to $18/t, plus $1/t per month for storage. There is an additional cost of €6/t to €7/t for loading out.

Delivery from Parkes to the port is by train. Mark commented that the region needs a dedicated grain train system to help the efficiency of transport and delivery.

He noted that the system used for coal is only about one-fifth of the cost associated with the handling, transport and delivery of wheat. “It's all about organisation,” he stated.

Mechanisation

Equipment on the farm is well-considered and there did not appear to be surplus machine capacity. That said, there is some scope to do contracting work, specifically spraying and harvesting.

The wide wheel track on the Claas Xerion for the controlled traffic operation.

The farm operates a controlled traffic system, which minimises the tracks on the land. This is seen to be quite advantageous and will be continued into the future.

The planting system on the farm uses a very flexible Excel precision drill, which can very simply alter row widths when planting different crops.

This technology has also enabled the planting of crops between the stubble rows of the previous crop with the help of RTK autosteer technology.

Following crops are sown between the stubble rows of the previous crop with the help of controlled traffic and precision autosteer.

This means that new roots can follow in the channels of old roots and empty root channels can help with water percolation into the soil for future use.

Machines always follow in the same tracks and this is helping to minimise compaction on soil types that might be described as quite weak, due to their lack of organic matter and the basic loss of soil structure.

Kangaroos were easier to find when we got into the quieter countryside.

The 3,800ha are sown with a single drill, sprayed with a single self-propelled RoGator fitted with a Croplands sprayer and harvested with a single Case combine.

The spread of crops and planting and harvest dates helps to make this possible and the low level of machinery investment helps overall profitability.

SHARING OPTIONS