The increase in international feed prices has been primarily driven by the escalation in maize prices.

This has happened because of higher US prices and these, in turn, were driven by huge demand for US exports.

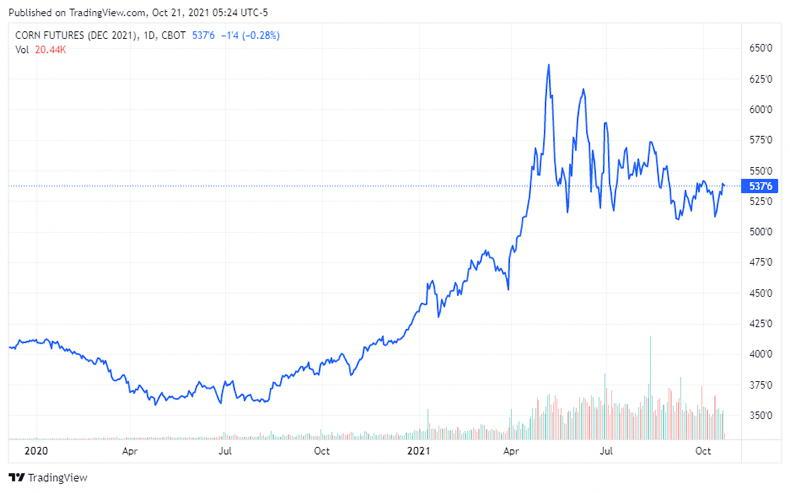

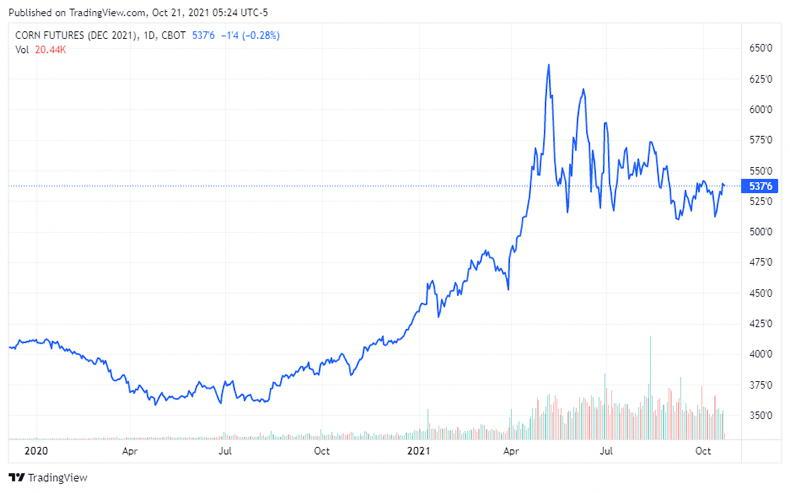

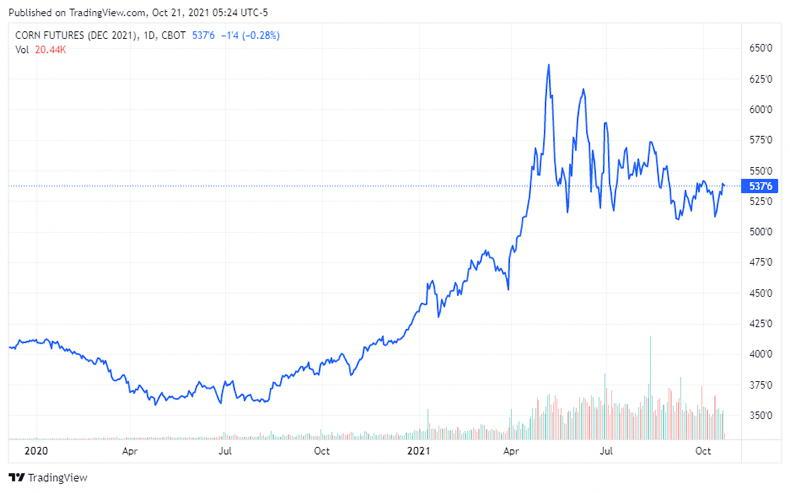

Having been trading as low as US$3.6 per bushel (bu) during much of the first half of 2020, maize prices escalated to a peak of almost $6.40/bu in May 2021, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Chicago December ’21 futures price for maize from January 2020 to mid-October 2022.

While this was the peak value for December maize on the Chicago market, prices have remained significantly higher in 2021 than they had been in 2020 and before.

Demand was bigger than supply despite the big US harvest.

Drought-driven problems in South America impacted on supply and demand was growing.

For Irish importers, this has taken maize price from sub €180/t out of Irish ports to in excess of €280/t currently. And increasing freight costs may add to this.

Freight

Bulk freight cost has become a serious issue in recent weeks, which may add further to the cost of imported feeds. Nearby freight costs have about doubled but the bigger problem may be accessing ships to begin with. This could apply to every feed that is still to come into the country and it points to the folly of relying so heavily on imported products.

The story on maize

For many years, imported maize has had a significant impact on the price of all other grains here because it was in an oversupply situation globally and it was sold at whatever price to move it away from the place of production.

However, in about August 2020, it became apparent that the demand for maize in different parts of the world had increased substantially and unexpectedly. At that point, we were in the global pandemic and there had been fears that the overall demand for maize would fall because of:

The expected reduction in global economic activity. Uncertainly over logistical capability. The reduced demand for bioethanol in the US.However, this changed in August 2020. Export demand from the US, from China in particular, exceeded what had been expected and concerns arose for the overall supply and availability of global maize.

Global prices began to rise and they continued to do so until that peak in May 2021.

While Chicago maize prices have been up and down considerably since then, they are floating between $5.30/bu and $5.40/bu in US terms, which is significantly higher than the $3.60 that had existed in previous years. This is likely to have been the price level against which much of our Irish maize imports had been based for the 2020/21 winter feeding season, even though much of out imports come from elsewhere.

Cereals are interchangeable

While individual cereals normally occupy specific market niches, they are in many respects interchangeable, especially in the feed grains market.

Maize can and has displaced barley here in the past and the opposite would appear to be the case this year, again based on price. Those Chicago maize prices stated previously represent a 47% price increase in US maize futures but the prices ex port in Ireland have increased even more (roughly 55%) due to the many challenges of logistics and shipping costs.

Imported maize here will have risen from under €180/t for forward purchases during the early part of 2020 to around €280/t currently.

The interchangeable nature of cereals in the feed market means that a surplus on one can pull down the others while a considerable deficit can pull all prices up. The net availability of all cereals is what really matters because a scarcity in one can be filled by another but if the total supply is not sufficient then prices will rise to help ration supply.

For much of the past 12 months, maize has been the market driver but wheat took over in the driver’s seat since harvest, as many global harvests disappointed. This may continue to be the case as a result of considerable winter crop failure across central Europe where drought conditions have badly hit crop germination.

It seem inevitable that feed costs will be substantially higher over the coming months.

Other feeds

Many other feeds are byproducts of cereals, so higher cereal prices will frequently mean higher prices for these feeds – maize gluten, maize distillers, brewers’ grains and distillers, etc. All of these increases combined have led to the significant price increases seen in feed prices here over the past 12 months.

Many other feeds arise from oilseeds and that whole complex has increased considerably in price also.

In May 2020, soya beans (not meal) traded at $8.40/bu for Chicago November 2021 contracts. This is now $12.40/bu, having been as high as £14.80/bu last June.

Oilseed rape for November started this year at around €400/t on the MATIF November market. Last week, the same contract almost broke €700/t. The story on palm kernel is broadly similar.

While many farmers will be aware of the increased feed prices, few will be aware of the almost continuous record global grain production levels that have occurred since the late 2000s and the phenomenal increases in global production.

In 2002, the global grain production (excluding rice) was 1,447m tonnes. This year that production number is forecast to be 2,289m tonnes. That is an additional 842mt.

That level of increased production amounts to over 44.315m tonnes extra every year for the past 19 years. That is equivalent to the current German grain harvest.

The impact of these global price changes is also reflected in native cereal prices, as shown in Figure 2.

This shows the dramatic change in the maize price and the relative value of the crop over the period. Maize has moved from being a little cheaper than wheat to a more expensive feed option than both wheat and barley.

Bad autumn weather across much of Europe in autumn 2019 saw a significant reduction in winter crop planting and much of that area subsequently found its way into spring barley. This left a lot more barley in the harvest of 2020 and barley price was forced to carry a significant discount below wheat in order to get it into rations to compete with maize.

High demand

This can be seen in Figure 2 which also shows that this discount has now dropped back under €10/t on wheat as native grains are in high demand.

The other big element of feed cost increase has been protein. While many of the mid proteins are byproducts of the cereals industry, soya bean meal has also seen significant price escalation (Figure 3).

This figure shows two exceptional peaks over the past two years – the first one in April 2020 related to the overall delay in getting crops planted in the US due to bad weather and fears that total production would be reduced.

The second and even higher spike in the early months of 2021 related to logistical issues arising from a strike in the crushing plants in Argentinian ports, followed by a fire causing the loss of product and storage capacity in a major unloading facility in Cork.

While prices eased back from those temporary spikes, they have remained considerably higher than previously.

The average ex port soya bean meal price for June to September 2020 (the flat part at the bottom of the curve) was €343/t while the average for June to mid-October 2021 was €416/t (again, the flat part of the end of the line). This is an average difference of €73/t between these two periods in time.

One of the other protein crops we import would be rapeseed cake. Oilseed rape prices have also seen very significant increase from 2020 until now, with futures prices having moved from an average of €377/t in 2020 to just under €700/t last week.

There has been considerable escalation in all cereal and feed prices over the past six months, in particular. This was primarily driven by tightness in supply relative to demand but now freight and logistical issues are compounding the situation.

As of now, it seems next year’s South American harvest will be a critical factor as to whether this situation will change next year but we could also see demand for feeds decrease in response to the high prices.

Tightness in supply has been a major factor in recent grain price increases.Global grain production has been increasing at the rate of an additional 44mt per annum for nearly two decades.2021 produced yet another record global production, estimated at 2,289mt.Logistics are likely to add to the problems in the coming months.

The increase in international feed prices has been primarily driven by the escalation in maize prices.

This has happened because of higher US prices and these, in turn, were driven by huge demand for US exports.

Having been trading as low as US$3.6 per bushel (bu) during much of the first half of 2020, maize prices escalated to a peak of almost $6.40/bu in May 2021, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Chicago December ’21 futures price for maize from January 2020 to mid-October 2022.

While this was the peak value for December maize on the Chicago market, prices have remained significantly higher in 2021 than they had been in 2020 and before.

Demand was bigger than supply despite the big US harvest.

Drought-driven problems in South America impacted on supply and demand was growing.

For Irish importers, this has taken maize price from sub €180/t out of Irish ports to in excess of €280/t currently. And increasing freight costs may add to this.

Freight

Bulk freight cost has become a serious issue in recent weeks, which may add further to the cost of imported feeds. Nearby freight costs have about doubled but the bigger problem may be accessing ships to begin with. This could apply to every feed that is still to come into the country and it points to the folly of relying so heavily on imported products.

The story on maize

For many years, imported maize has had a significant impact on the price of all other grains here because it was in an oversupply situation globally and it was sold at whatever price to move it away from the place of production.

However, in about August 2020, it became apparent that the demand for maize in different parts of the world had increased substantially and unexpectedly. At that point, we were in the global pandemic and there had been fears that the overall demand for maize would fall because of:

The expected reduction in global economic activity. Uncertainly over logistical capability. The reduced demand for bioethanol in the US.However, this changed in August 2020. Export demand from the US, from China in particular, exceeded what had been expected and concerns arose for the overall supply and availability of global maize.

Global prices began to rise and they continued to do so until that peak in May 2021.

While Chicago maize prices have been up and down considerably since then, they are floating between $5.30/bu and $5.40/bu in US terms, which is significantly higher than the $3.60 that had existed in previous years. This is likely to have been the price level against which much of our Irish maize imports had been based for the 2020/21 winter feeding season, even though much of out imports come from elsewhere.

Cereals are interchangeable

While individual cereals normally occupy specific market niches, they are in many respects interchangeable, especially in the feed grains market.

Maize can and has displaced barley here in the past and the opposite would appear to be the case this year, again based on price. Those Chicago maize prices stated previously represent a 47% price increase in US maize futures but the prices ex port in Ireland have increased even more (roughly 55%) due to the many challenges of logistics and shipping costs.

Imported maize here will have risen from under €180/t for forward purchases during the early part of 2020 to around €280/t currently.

The interchangeable nature of cereals in the feed market means that a surplus on one can pull down the others while a considerable deficit can pull all prices up. The net availability of all cereals is what really matters because a scarcity in one can be filled by another but if the total supply is not sufficient then prices will rise to help ration supply.

For much of the past 12 months, maize has been the market driver but wheat took over in the driver’s seat since harvest, as many global harvests disappointed. This may continue to be the case as a result of considerable winter crop failure across central Europe where drought conditions have badly hit crop germination.

It seem inevitable that feed costs will be substantially higher over the coming months.

Other feeds

Many other feeds are byproducts of cereals, so higher cereal prices will frequently mean higher prices for these feeds – maize gluten, maize distillers, brewers’ grains and distillers, etc. All of these increases combined have led to the significant price increases seen in feed prices here over the past 12 months.

Many other feeds arise from oilseeds and that whole complex has increased considerably in price also.

In May 2020, soya beans (not meal) traded at $8.40/bu for Chicago November 2021 contracts. This is now $12.40/bu, having been as high as £14.80/bu last June.

Oilseed rape for November started this year at around €400/t on the MATIF November market. Last week, the same contract almost broke €700/t. The story on palm kernel is broadly similar.

While many farmers will be aware of the increased feed prices, few will be aware of the almost continuous record global grain production levels that have occurred since the late 2000s and the phenomenal increases in global production.

In 2002, the global grain production (excluding rice) was 1,447m tonnes. This year that production number is forecast to be 2,289m tonnes. That is an additional 842mt.

That level of increased production amounts to over 44.315m tonnes extra every year for the past 19 years. That is equivalent to the current German grain harvest.

The impact of these global price changes is also reflected in native cereal prices, as shown in Figure 2.

This shows the dramatic change in the maize price and the relative value of the crop over the period. Maize has moved from being a little cheaper than wheat to a more expensive feed option than both wheat and barley.

Bad autumn weather across much of Europe in autumn 2019 saw a significant reduction in winter crop planting and much of that area subsequently found its way into spring barley. This left a lot more barley in the harvest of 2020 and barley price was forced to carry a significant discount below wheat in order to get it into rations to compete with maize.

High demand

This can be seen in Figure 2 which also shows that this discount has now dropped back under €10/t on wheat as native grains are in high demand.

The other big element of feed cost increase has been protein. While many of the mid proteins are byproducts of the cereals industry, soya bean meal has also seen significant price escalation (Figure 3).

This figure shows two exceptional peaks over the past two years – the first one in April 2020 related to the overall delay in getting crops planted in the US due to bad weather and fears that total production would be reduced.

The second and even higher spike in the early months of 2021 related to logistical issues arising from a strike in the crushing plants in Argentinian ports, followed by a fire causing the loss of product and storage capacity in a major unloading facility in Cork.

While prices eased back from those temporary spikes, they have remained considerably higher than previously.

The average ex port soya bean meal price for June to September 2020 (the flat part at the bottom of the curve) was €343/t while the average for June to mid-October 2021 was €416/t (again, the flat part of the end of the line). This is an average difference of €73/t between these two periods in time.

One of the other protein crops we import would be rapeseed cake. Oilseed rape prices have also seen very significant increase from 2020 until now, with futures prices having moved from an average of €377/t in 2020 to just under €700/t last week.

There has been considerable escalation in all cereal and feed prices over the past six months, in particular. This was primarily driven by tightness in supply relative to demand but now freight and logistical issues are compounding the situation.

As of now, it seems next year’s South American harvest will be a critical factor as to whether this situation will change next year but we could also see demand for feeds decrease in response to the high prices.

Tightness in supply has been a major factor in recent grain price increases.Global grain production has been increasing at the rate of an additional 44mt per annum for nearly two decades.2021 produced yet another record global production, estimated at 2,289mt.Logistics are likely to add to the problems in the coming months.

SHARING OPTIONS