I attended a lunch in London almost three years ago where most of the guests were economic experts from European and American financial companies. Our host posed a simple question: if there is another eurozone crisis, which country will be the trigger?

At the time, the fashionable answer was Greece, whose problems unfortunately have not been solved in the interim. The assembled luminaries in London were unanimous in taking a relaxed view on Greece: the big problem would be Italy and they were prescient. Events in the last few months have confirmed that the existential threat to the eurozone was never likely to be a small country on the edge of the continent.

Greece, in the limit, could have been sacrificed, as could Portugal or Ireland, currently in daily receipt of warm hugs from our European partners over the Brexit threat. It is just a few short years since the Irish Government was threatened with Greek-style treatment, closure of the Irish banking system as punishment for unwillingness to pay bank bondholders to whom the bankrupt State owed nothing. This, it should not be forgotten, was done with the knowledge and connivance of our new best friends in continental Europe, led by Jean-Claude Trichet and the European Central Bank. European solidarity with smaller members is, for France and Germany, an occasional choice from an a la carte menu.

If the fundamental flaws in the common currency project are to be revealed again, the crisis was always likely to emerge first in Italy. And Italy will be treated differently from Greece, or any other small country in trouble, because a financial collapse in Italy is unimaginable. It would threaten the survival of the common currency and could precipitate a worldwide re-run of the 2008 banking disaster.

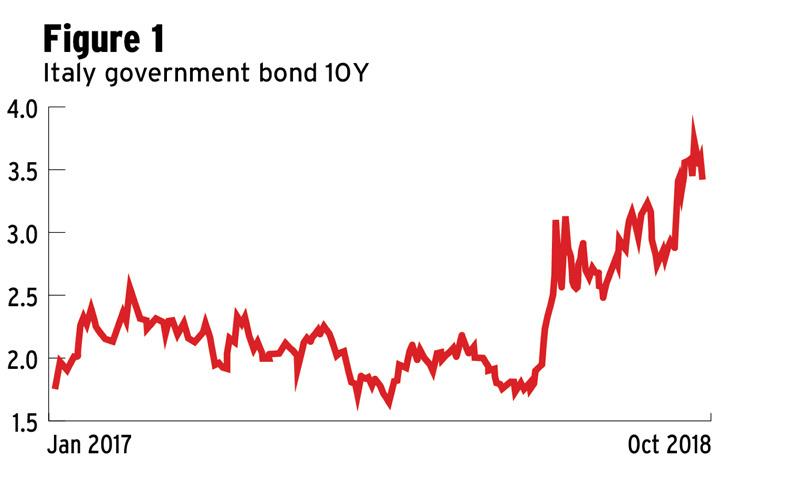

Figure 1 shows the fluctuations in the cost to the Italian government of borrowing 10-year money.

That cost has doubled over the last six months as a new and populist government has embarked on a conflict with the European Union over budget policy. The populists won the recent election with promises of a spending spree and tax cuts. The problem is that Italy is already over-borrowed and government plans to increase the deficit to 2.4% next year will make matters worse.

If Italy was enjoying strong economic growth and had a low debt level, nobody would get too excited about a deficit of the size that is planned. But in addition to a heavy historical debt level, Italy has had negligible economic growth for decades, the poorest performance of any large European country.

The result is that two almost identical bonds maturing in 2028 are priced in the market at €142 for the German version but only €110 for the Italian variant, a discount of almost a quarter. Both are denominated in euros of course and both offer the same annual coupon. The markets fear that Italy might default, or that it might leave the euro and re-denominate its debt into a new and weaker currency.

The eurozone bond market collapse in 2010 eventually forced Greece, Ireland and Portugal to cease market borrowing altogether. One of the reasons it never reached Italy, where a bond market crash would have much bigger international consequences, is because successive Italian governments acted to control borrowing, the policy now abandoned. Markets have been calmer too since the European Central Bank commenced its mammoth purchases of eurozone sovereign debt, due to end in December.

Ireland’s borrowing costs have been rising along with the general trend but there has been no tendency to group Ireland (or Portugal) in the naughty club with Italy, as happened last time round. While Ireland’s economy has been growing and the deficit is finally headed back towards zero, events in Italy should remind the Irish Government that every eurozone member with a high debt burden is vulnerable. Re-classification into the naughty club can happen very quickly – all it takes is a growth slowdown and an election win for the parties making the biggest promises. Now how could that ever happen in Ireland?

SHARING OPTIONS