With the UK Prime Minister putting a vote on the EU withdrawal agreement back until the middle of January, just 10 weeks form Brexit day on 29 March, the risk of a no-deal Brexit increases all the time. As Parliament went into its Christmas break and due to resume the withdrawal debate on 7 January, there is little indication of it being accepted by Parliament. The closer we get to departure, the less likely there is to be another option, so even though Parliament isn’t supportive of a no-deal scenario, it may very well happen.

Development of reduced tariff trade

Virtually all studies suggest a severe economic impact, up to 8% of GDP on the Irish and UK economies if there is a no-deal Brexit and a much worse situation for agriculture. This is because in the global trade liberalisation process that began with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) after World War II, agriculture was the one sector that didn’t take to trade liberalisation the way other industries did. While countries were prepared to be adventurous in general trade, there was a much more protective approach towards domestic agriculture. This was partially driven by the dependence on homegrown food during the two major wars in the first half of the 20th century and consequential food rationing. This was also the driver for establishing the Common Agricultural Policy in 1962 in the fledgling EEC, when food scarcity was still real.

As global trade liberalised in the latter part of the last century and the beginning of this one, tariffs were reduced or eliminated at a global level for many products and, within trade blocks like the EU, abandoned altogether. However, the World Trade Organisation, the successor to GATT which has most countries of the world as members, has an agreed tariff schedule for members and within this, agricultural produce is the category that carries the highest tariffs, up to 100% in the case of some beef products.

Disproportionate impact

When the UK leaves the EU on 29 March, trade between the UK and the rest of the world will be conducted under WTO rules. That means agricultural produce will carry tariffs that are hugely disproportionate to the value of the trade. Ireland’s trade with the UK best illustrates the point. Ireland is a relatively small trading partner with the UK and has just 5% of the EU27’s total trade with the UK. However. such is the high level of tariffs on agricultural products, which make up a large part of Ireland’s trade with the UK, this 5% of trade would account for 19% of all tariffs that would be paid by the EU27.

At the other extreme is Germany, which is the largest exporter to the UK of the EU27 and has 28% of the entire EU27 trade with the UK. However, despite having more than five times Ireland’s trade with the UK, Germany would actually be liable for less tariffs on this under WTO than Ireland at just under 18% compared with Ireland’s 19%.

This is because agriculture is such a huge part of Irish exports to the UK with a huge tariff, up to 100% in the case of some cuts of beef. On the other hand, cars and car parts are the backbone of German trade with the UK, and cars carry a WTO tariff of just 7.9%. This is an extra cost but not a deal breaker – it would mean a €50,000 BMW would cost €54,000 with a WTO tariff. However, if we look at Irish manufacturing beef used in mince and currently selling wholesale in the UK at €3.50/kg, with a 100% tariff this would cost €7.00/kg and that would be a deal breaker.

Brexit won’t impact 20 countries

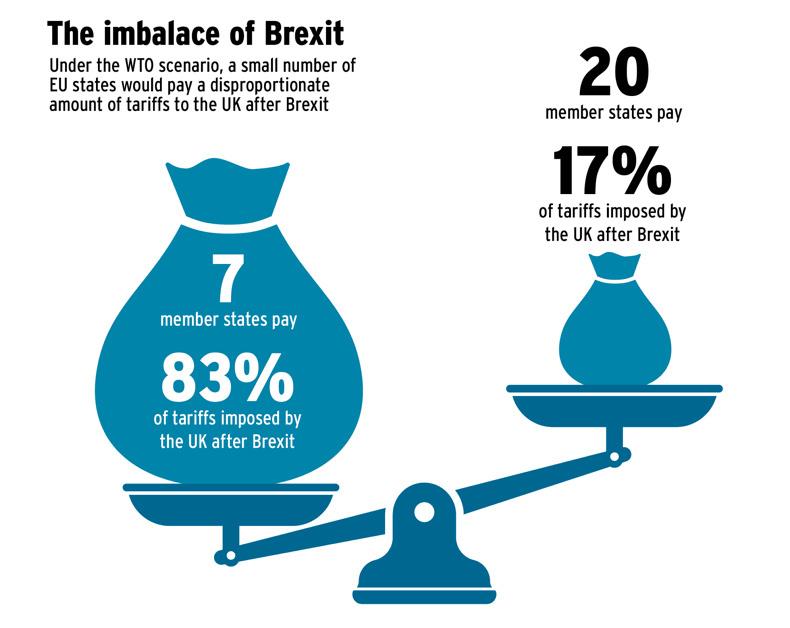

Looking at the EU countries with the majority of EU27 exports to the UK, we can see that seven countries would pay 83% of all EU tariffs if it was a no-deal outcome and trade was to take place under WTO rules. All of these do much more business with the UK than Ireland does but wouldn’t pay anywhere near as much tariff as Ireland under WTO rules.

NI and Scotland

While farmers in Northern Ireland and Scotland would be in a strong position for internal UK sales, they too would be hit hard by WTO tariffs on their exports. In NI, milk sales to processors south of the border would be wiped out with tariffs, as would lamb sales to southern processors who buy almost half of NI’s lamb production. Scotland is less exposed on beef exports to the EU27, with just 10 – 15% of sales outside the UK but up to one-third of lamb sales currently to mainland Europe would be effectively wiped out with WTO tariffs.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: