My sock was taken last week. I definitely had two, but after a night’s sleep only one was there. I looked high up and low down and still it could not be found. Where could it have gone? It was simply bad luck.

There was a time in Ireland when bad luck was blamed on fairies. These other-world creatures existed in parallel with the Irish peasantry for centuries. Feared and respected they lived in liosanna, raths or cairns. Indeed their homes are dotted in every corner of the Irish landscape.

From the stories of fairies, folklore grew. These grew into stories and traditions. Over the centuries the folklore of great deeds from the other world charmed and enthralled all. However, those in power saw these beliefs as backward and ignorant.

School children make history

During the great Irish literary revival of the 1890s, writers like WB Yeats, Lady Gregory and Douglas Hyde drew on these traditions. Kaithleen Ní Houlihan and The Travelling Man are two such plays that deal with folklore.

In the 1930s a drive was made to collect stories, and The Folklore Commission was set up. School children collected stories, which were then recorded, and 80 years later these stories are part of a rich legacy of our past. They are a primary source of history for schools and scholars alike.

From this folklore the tradition of pishogs grew. Certain things could be done and not done. For example during a land eviction broken egg shells were placed in the ground so that crops would not grow for the next tenant. If you lit a fire in your house and sparks came out, this was seen as a sign that money was coming your way. If a straw fell on the ground a visitor was coming.

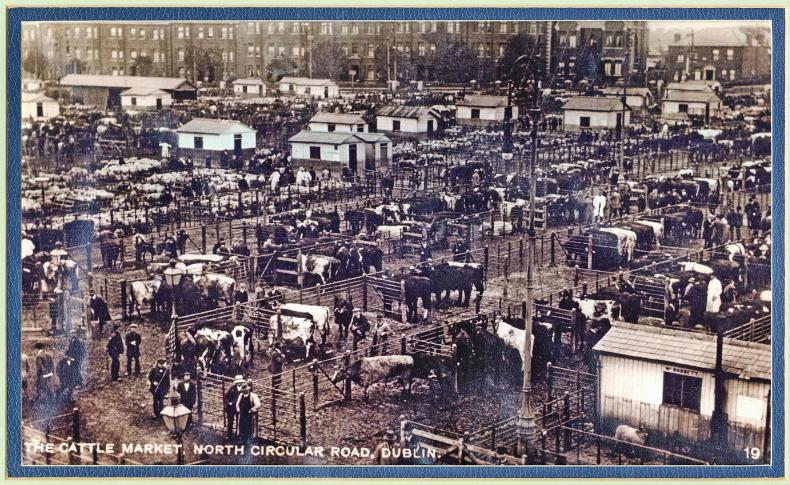

However not all pishogs were linked with the house and livestock: fairs have a rich array of pishogs too. In North Kilkenny if a farmer got beestings for a calf from another farmer, a penny was given. This was to insure that bad luck would not descend on the herd.

If you ran into a red-haired woman on the way to a fair you turned back, as the price you would get would be poor. It’s also common practice to give “luck” when selling livestock. This means returning a portion of the sale price to the seller when a deal is made.

Pishogs for all stages of life

All rites of passage – from birth to death with everything in between – were marked by ritual. Great emphasis was placed on conception and childbearing.

In some parts of Ireland, if a malicious person tied a knot in a handkerchief as the couple exchanged their vows, it was thought to prevent them from conceiving. If a pregnant woman came close to a hare, it was believed her child could have a hare lip. Indeed pregnant women were not supposed to enter a graveyard, in case they came in contact with the dead.

Child birth had its own set of customs. If a child entered the world at night they were thought to have the powers to see the other world. May day was a very important day to be born, as it insured the child would be granted luck all their lives. And to this day, many people would be familiar with the custom that the seventh son of a seventh son has the power to cure all aliments.

There are many customs associated with marriage. If a bride lived down a lane, a fire would be lit to show the other world that the girl was leaving to pastures new.

If young boys were not invited to the wedding reception they dressed as straw men and kidnapped the bride for a barrel of beer. There are slight differences in this custom in different parts of Ireland, but the tradition remains. Their presence was believed to bring luck, wealth and health to the newlyweds.

It is death that carries the most traditions. In connection with the fairies, the banshee cries and combs her hair when death is near. Tradition states that she follows families with “Mac” or “O” in their names.

During the traditional wake the clock was stopped at the time of death, and two coins were placed on the eyes of the deceased to pay the boatman as they crossed the river into the next world. Another pishog ,which is still practiced in parts today, is if a robin enters a house, death is near.

While the customs may differ from village to village, many of these traditions are still practiced. Fairy rings are still secret places on many farms; all connecting the land and the other world.

The writer John McGahern summed it up when he said: “Ireland is a peculiar society in the sense that it was a 19th century society up to about 1970, and then it almost bypassed the 20 century.”

Irish people still practice a rich array of these old pishogs, while many other societies have lost them. The land is where we come from and it’s where we all go. There’s a veil covering the unseen world and sometimes those that inhabit it come out to play. At least that’s what some of us would like to think. CL

SHARING OPTIONS