The Dutch have built a transparent milk pricing policy of which the core (or guaranteed) price is a European average price with a top-up or bonus that co-op management must justify.

In 2012, the bonus above the European average was worth 2.37c/litre and Frans suggests that 3c/litre is the target bonus. The co-op now has the size and capability to invest in new markets and is partnering up and buying companies in the high growth regions.

At the conference, Friesland Campina board member Frans Keurentjes briefly set out his co-op’s policy on: (1) milk pricing, and (2) co-op development and growth. Let me take each individually.

Milk pricing

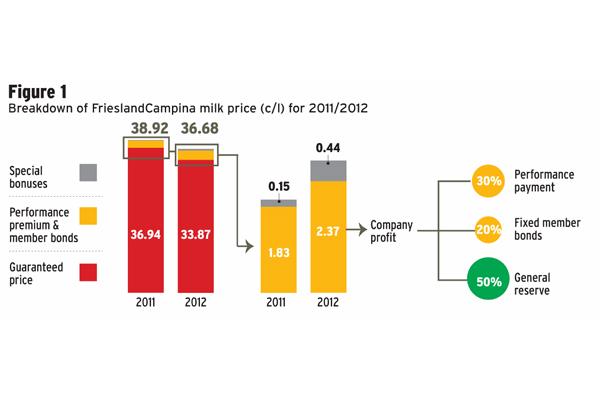

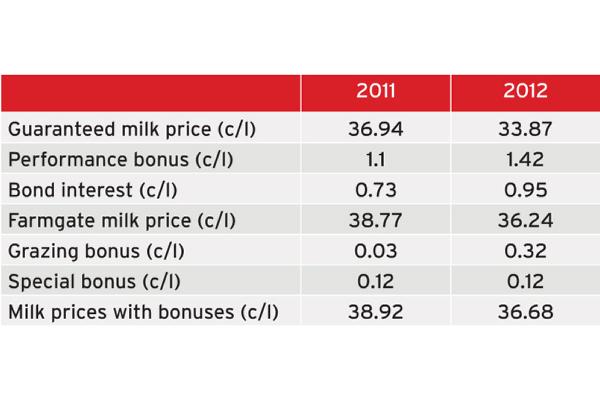

The price a Friesland Campina supplier obtains is made up of three distinct parts – (a) the core or guaranteed price, (b) the co-op performance bonus and (c) the conditional bonus which a supplier gets depending on if he is grazing.

The core or guaranteed milk price Dutch farmers get is based on the average milk price obtained in the countries surrounding Holland – namely Germany, Belgium, and Denmark. It reflects the price paid for approx 46 billion kg of milk (nine times the volume of milk produced in Ireland).

This European dipstick is used to reflect the market value for raw milk and is completely independent of whether Friesland Campina make money from selling the 10 billion kilos of milk they collect from Dutch farms. For the co-op, this is the minimum they need to pay to suppliers and this core price will decide whether the co-op makes a profit or not.

As you can see from Figure 1, this core or guaranteed milk price (red part of bar) makes up the majority of the milk price received by Dutch dairy farmers.

||PIC2||

On top of that, suppliers get bonuses that come from the profits of the business (see Figure 1 and Table 1). The profits of processing and selling milk are divided 50:50 – the first 50% is paid out to farmers in a milk price top-up and an interest rate return on fixed member bonds.

The second 50% is held for the general reserve. At the moment, there is a discussion among suppliers that instead of 50%, should this be 45% – slightly less for the general reserve.

So what does the breakdown mean for Dutch farmers? Essentially, it allows farmers to see what value creation or premiums co-op management are delivering.

It becomes clear to suppliers what premium they are getting on milk because they are part of Friesland Co-op giving them a sense of ownership.

At the conference, Frans said: “Like all co-ops, discussions on milk price are still not easy among suppliers but the fact that the core milk price and bonuses are split out definitely brings more transparency to the system of milk pricing for farmers.”

||PIC3||

Frans also explained at the conference that Friesland Campina had looked at fixing milk price for a portion of supply (similar to Glanbia and Connacht Gold) but had decided any of these types of schemes cost money with little or no advantage for the farmer. He said some farmers can hedge business with other organisations but Friesland Campina were not going to get involved in that space. Milk supplied to Friesland Campina from cows that are grazing for six hours for 120 days gets a premium which is costing the co-op €45m per year.

At the conference, Frans was asked if this was making money for the co-op. He answered: “The premium is costing the co-op about €45m per year, so that is what our management need to get back from the marketplace to make it break even.

||PIC4||

“At the moment, we get back about €15m to €17m each year, so, yes, it has been successful, but there is a money gap challenge for our co-op management to deal with.”

Co-op growth and development

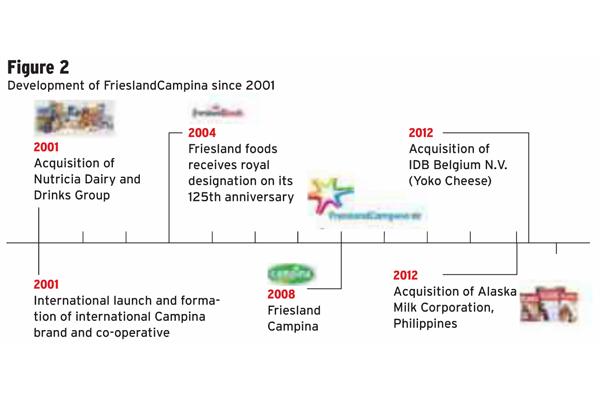

Friesland Campina has grown by a series of mergers and acquisitions to become a large-scale milk processor sitting in the top 10 of dairy companies worldwide, processing over 10 billion kilos of milk (twice Ireland’s production). The last 10 years has seen a number of key acquisitions, the most recent of which is Alaska Milk Corporation in the Philippines which gives them a foothold in a market of 100m consumers.

Frans explained: “When I’m explaining to Dutch farmers about where our milk goes, I say to them for every three cows you milk, one is used to supply milk for Holland, one for export to other parts of Europe and the third for exporting out of Holland.

“Exporting is, and will increasingly become, more important when quotas go and more milk is produced in Holland as forecasted.”

In more recent weeks, Friesland Campina bought a 7.5% stake in a New Zealand milk processor called Synlait which is owned by Chinese investors. Frans was asked why did that happen?

He replied: “We want positions globally because our co-op wants to process more milk. We want to be in markets where business is booming. We are also working with the major player in New Zealand, Fonterra, in Germany and Australia.

“We want to provide what consumers want and a position in Synlait is good for us and gets us a foothold indirectly in the Chinese market.

“We find we always struggle if we don’t strengthen our local position. The Chinese government don’t accept just doing business in the region, they want us to be committed. Over 6,000 of our 19,000 employees are working in China now.”

KENNEDY COMMENT

Light years ahead of where we are

The clarity of thinking and the transparency on returns to the Dutch farmer that Frans described makes most Irish co-ops and our marketing arm look like they are operating back in the 1970s.

This statement is not at all supposed to be disrespectful to the Irish co-ops or Irish Dairy Board as they box well above their weight division in many markets. However, the Dutch firm’s positioning for the future and their investment in building bridges into the high dairy growth regions on the face of it seems to be light years ahead of where we are.

The most basic example is our efforts at setting milk price. Think about how milk price is set in Ireland. If global markets are good, dairy farmers push their farmer representatives at individual co-op board level to argue with co-op management that the milk price needs to be improved to reflect what the market is returning that month.

Due to the lack of transparency and confusion about returns from other parts of the business, management are often forced to argue the price down. Product may have been sold in advance, tied into a contract or the co-op may be processing a product that is not returning such a high price.

For the majority of co-ops, an argument or debate on milk price will take up a large part of the monthly board meeting.

As Dairy Ireland suggest, what about the possibility of management guaranteeing a certain milk price and a year-end bonus system that would give some certainty to dairy farmers – similar to Friesland Campina?

It could be altered as the year progressed, depending on profits and returns, with a bonus payment paid at year-end reflecting trading surpluses.

In the same way, the Dutch co-op have the scale and capacity to invest long term in high growth rate markets. Almost one third of the Dutch co-op’s employees are working in China. Not even our largest player Glanbia has such resources in Asia. All the experts say that you need to invest in China if you want future success. Friesland are doing just that.

In the same way, while extolling the virtues of the Dutch set-up, I have to express the opinion that on-farm profitability for intensive dairy farming in Holland may be very small. Even at today’s high milk prices, Dutch farmers need every bonus that is possible to make a viable business.

SHARING OPTIONS