In the month of June, following my first year of secondary school, I was sent off to the Muskerry Gaeltacht of Cúil Aodha, hidden away in the Derrynasaggart Mountains, to learn my Irish. In addition to learning how to play ping-pong, dance The Siege of Ennis and sing the O’Riada mass, I also experienced my first crush on a beautiful young girl named Pádraigín.

She was a real beauty with jet black hair, perfect skin, and red-rosy cheeks and she had come to work for the summer to help the bean-an-tí. She was a shy girl with a bright beaming smile and sky-blue eyes.

At the end of the summer, having danced every dance with her at the céilí, I managed to pluck up the courage to give her a kiss and, in that moment, everything changed. It was as if, like in the great mythological tales, I had met the goddess and that embrace marked my initiation into a different world.

On Sundays, following mass, to relieve us of our taspy (slang for hyperness), all the boys were put on a forced march up Mullaghanish. On the way back, I would steal off across the Sullane to the little clearing in the woods dedicated to another goddess, Gobnait.

According to the legend, Gobnait originally hailed from Inis Oírr, the most easterly of the Aran Islands and settled in Baile Bhúirne when she came upon the auspicious sign of a herd of nine white deer grazing.

Local legends

There are many variations of local legends and accounts that retell how Gobnait, as a beekeeper, magically transformed her bees and bee skeps to miraculously help the local O’Herlihy chieftains.

The rival O’Donoghue family had come cattle-raiding while the O’Herlihys were away on a hunting foray in Kerry, and now devoid of their cattle the O’Herlihys were without subsistence or status. Their chieftain went to Gobnait for help.

At the promise of conversion, Gobnait went to one of her hives, said a little prayer and her straw bee skep magically turned into a brass war-faring helmet and all the winged bees disappeared.

When the chieftain looked up, he saw a huge ‘swarm’ of well-armed soldiers, neatly organised who would now do battle on his behalf. In no time at all, he re-secured his cattle, and the miraculous brass helmet was kept by the O’Herlihy family.

Thomas Crofton Corker, writing in 1825, tells us: “This relic is held by the Irish peasantry in such veneration that they will travel several miles to procure a drop of water from it, which, they imagine, if given to a dying relative or friend, will secure their ready admission into heaven.”

Other versions of the legend tell how Gobnait flung one of her bee skeps after the intruders and the stinging bees quickly brought the offenders to rule.

It was in 1951 that Seamus Murphy’s effigy of Gobnait was to be erected beside the remains of an ancient circular ruin, long regarded as Gobnait’s ‘kitchen’. While digging the foundation for the statue, a few stray finds prompted a full archaeological excavation that was undertaken by Professor Michael J O’Kelly of UCC.

O’Kelly dated the site generally to the early medieval period (5-12th century) and he uncovered significant evidence of crucibles, slag and items associated with metalwork and smithing.

In Irish mythological tradition, the great god of smith-working was Goibhniu. He is the mythical smith of the Tuatha De Dannan and, according to legend, made his compatriots magical spears that never missed their target. It is likely that the smith god, Goibhniu, was venerated in Báile Bhuirne and the much-revered female figure of Gobnait grew out of this earlier tradition.

This might go some way to explain her association with metal objects: the brass helmet or bell and various bowls or crucibles that feature large in the local folk memory connected with her.

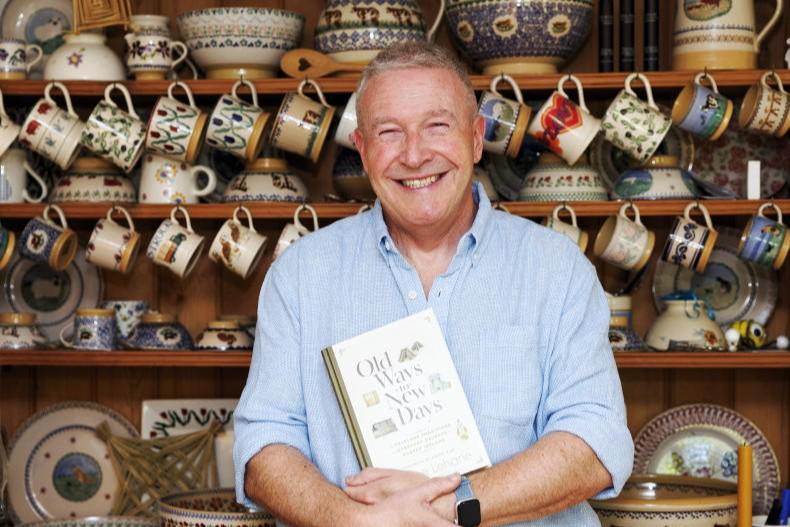

Shane Lehane is an academic folklorist who teaches at CSN College of Further Education and University College Cork.

Celebrating Gobnait

Gobnait’s feast day was earlier this week on 11 February and this date may offer an important clue to understanding her strong connection with bees. In 1752, the changeover from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar caused the removal of 11 days from the calendar. Very often, two different calendars were in use and people celebrated old and new versions of festivals with a difference of 11 days in between.

Gobnait’s feast day makes her a cognate of the most significant female deity,

The feast of St Brigid is 1 February. The ancient name for Brigid’s festival is Imbolc or Oimelc: the festival of birth, milk and new life. From this point in the calendar onwards, with the slow increase in daylight, the buds swell, the sap rises, the birds begin to build their nests and new beginnings emerge from the slumber and stasis of the dormant, cold, winter months.

At this juncture of the year, in and around Brigid’s and Gobnait’s feast days, the first crocuses, snowdrops and buttercups break the grass cover and announce the new cycle of fertility. If all is well, to the delight of the beekeeper, the first bees will emerge from the hives on short cleansing flights.

The new cycle of the New Year has begun. The beehive, with its queen at its centre and the swarms of workers who pollinate the natural world, represent the quintessential symbol and mechanism for rebirth, regeneration, and fertility. Gobnait of Baile Bhúirne is now revered as a much-loved local female saint and her connection with bees and her feast day establishes her as a fundamental symbol of female fecundity.

Moreover, she embodies a figure who informs us about the continual cycle of birth, growth, fruition, and death that shapes how we live and learn, each and every year.

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: shane.lehane@csn.ie

Read more

Folklore: by the light of the silvery moon

Folklore: Biddy Boys and Brídeogs

In the month of June, following my first year of secondary school, I was sent off to the Muskerry Gaeltacht of Cúil Aodha, hidden away in the Derrynasaggart Mountains, to learn my Irish. In addition to learning how to play ping-pong, dance The Siege of Ennis and sing the O’Riada mass, I also experienced my first crush on a beautiful young girl named Pádraigín.

She was a real beauty with jet black hair, perfect skin, and red-rosy cheeks and she had come to work for the summer to help the bean-an-tí. She was a shy girl with a bright beaming smile and sky-blue eyes.

At the end of the summer, having danced every dance with her at the céilí, I managed to pluck up the courage to give her a kiss and, in that moment, everything changed. It was as if, like in the great mythological tales, I had met the goddess and that embrace marked my initiation into a different world.

On Sundays, following mass, to relieve us of our taspy (slang for hyperness), all the boys were put on a forced march up Mullaghanish. On the way back, I would steal off across the Sullane to the little clearing in the woods dedicated to another goddess, Gobnait.

According to the legend, Gobnait originally hailed from Inis Oírr, the most easterly of the Aran Islands and settled in Baile Bhúirne when she came upon the auspicious sign of a herd of nine white deer grazing.

Local legends

There are many variations of local legends and accounts that retell how Gobnait, as a beekeeper, magically transformed her bees and bee skeps to miraculously help the local O’Herlihy chieftains.

The rival O’Donoghue family had come cattle-raiding while the O’Herlihys were away on a hunting foray in Kerry, and now devoid of their cattle the O’Herlihys were without subsistence or status. Their chieftain went to Gobnait for help.

At the promise of conversion, Gobnait went to one of her hives, said a little prayer and her straw bee skep magically turned into a brass war-faring helmet and all the winged bees disappeared.

When the chieftain looked up, he saw a huge ‘swarm’ of well-armed soldiers, neatly organised who would now do battle on his behalf. In no time at all, he re-secured his cattle, and the miraculous brass helmet was kept by the O’Herlihy family.

Thomas Crofton Corker, writing in 1825, tells us: “This relic is held by the Irish peasantry in such veneration that they will travel several miles to procure a drop of water from it, which, they imagine, if given to a dying relative or friend, will secure their ready admission into heaven.”

Other versions of the legend tell how Gobnait flung one of her bee skeps after the intruders and the stinging bees quickly brought the offenders to rule.

It was in 1951 that Seamus Murphy’s effigy of Gobnait was to be erected beside the remains of an ancient circular ruin, long regarded as Gobnait’s ‘kitchen’. While digging the foundation for the statue, a few stray finds prompted a full archaeological excavation that was undertaken by Professor Michael J O’Kelly of UCC.

O’Kelly dated the site generally to the early medieval period (5-12th century) and he uncovered significant evidence of crucibles, slag and items associated with metalwork and smithing.

In Irish mythological tradition, the great god of smith-working was Goibhniu. He is the mythical smith of the Tuatha De Dannan and, according to legend, made his compatriots magical spears that never missed their target. It is likely that the smith god, Goibhniu, was venerated in Báile Bhuirne and the much-revered female figure of Gobnait grew out of this earlier tradition.

This might go some way to explain her association with metal objects: the brass helmet or bell and various bowls or crucibles that feature large in the local folk memory connected with her.

Shane Lehane is an academic folklorist who teaches at CSN College of Further Education and University College Cork.

Celebrating Gobnait

Gobnait’s feast day was earlier this week on 11 February and this date may offer an important clue to understanding her strong connection with bees. In 1752, the changeover from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar caused the removal of 11 days from the calendar. Very often, two different calendars were in use and people celebrated old and new versions of festivals with a difference of 11 days in between.

Gobnait’s feast day makes her a cognate of the most significant female deity,

The feast of St Brigid is 1 February. The ancient name for Brigid’s festival is Imbolc or Oimelc: the festival of birth, milk and new life. From this point in the calendar onwards, with the slow increase in daylight, the buds swell, the sap rises, the birds begin to build their nests and new beginnings emerge from the slumber and stasis of the dormant, cold, winter months.

At this juncture of the year, in and around Brigid’s and Gobnait’s feast days, the first crocuses, snowdrops and buttercups break the grass cover and announce the new cycle of fertility. If all is well, to the delight of the beekeeper, the first bees will emerge from the hives on short cleansing flights.

The new cycle of the New Year has begun. The beehive, with its queen at its centre and the swarms of workers who pollinate the natural world, represent the quintessential symbol and mechanism for rebirth, regeneration, and fertility. Gobnait of Baile Bhúirne is now revered as a much-loved local female saint and her connection with bees and her feast day establishes her as a fundamental symbol of female fecundity.

Moreover, she embodies a figure who informs us about the continual cycle of birth, growth, fruition, and death that shapes how we live and learn, each and every year.

Shane Lehane is a folklorist who works in UCC and Cork College of FET, Tramore Road Campus. Contact: shane.lehane@csn.ie

Read more

Folklore: by the light of the silvery moon

Folklore: Biddy Boys and Brídeogs

SHARING OPTIONS