Liver fluke is a common parasite in Ireland and the mild, wet conditions are an ideal environment for it to thrive. Cattle infected with liver fluke are usually chronically affected, with negative outcomes in terms of growth rates, achievement of growth targets, fertility and milk yield.

A study in Irish steers showed that animals with evidence of liver fluke in the factory were lighter by an average of 36kg liveweight at a standardised slaughter age.

In sheep, migration of immature flukes to the liver can cause severe damage, resulting in sudden death. Liver fluke is also associated with Black disease, a clostridial infection, preventable through vaccination.

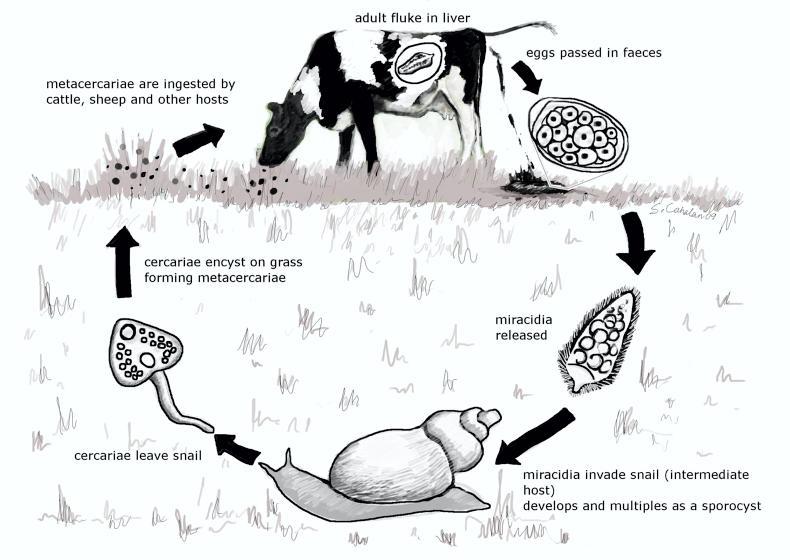

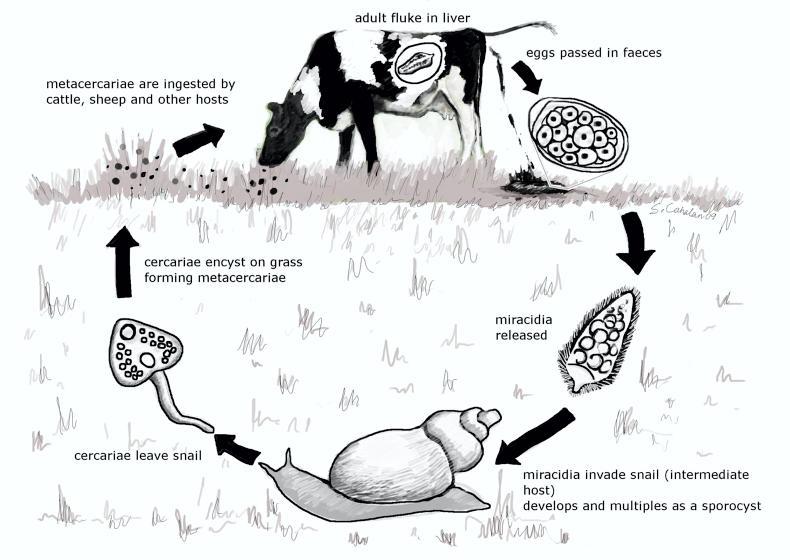

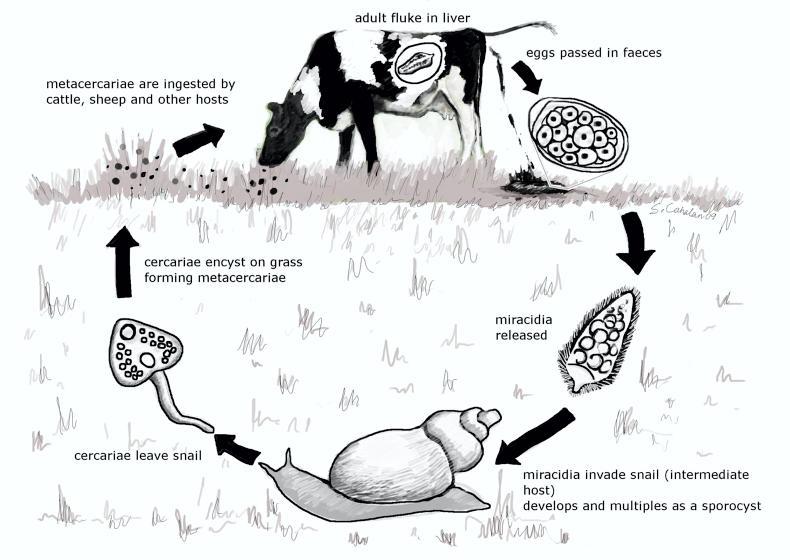

Liver fluke needs an intermediate host – the mud snail – to complete its life cycle. These snails live in poorly-drained, water-logged areas on the farm. If animals are infected with adult liver fluke while on pasture, the fluke eggs are released, hatch and enter the snails, where they undergo further development.

The fluke parasites leave the snails and return to the pasture, usually from late summer to autumn, as an infective stage that can then be eaten by grazing animals (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Life cycle of liver fluke.

Control of liver fluke usually involves treating effectively at housing to prevent production losses in cattle. Killing the parasites over the housing period will also reduce pasture contamination in the following spring. Prevent animals from grazing near the waterlogged areas during the high-risk period from late summer onwards. Or drain the land, if possible. If a farm is free of liver fluke, prevent the parasites from spreading to the farm with a quarantine period and treating all animals brought in before placing them on pasture. A long-term strategy is breeding cattle that are less likely to become infected with liver fluke. Sire breeding values for genetic resistance to liver fluke are now available from the ICBF. How to know if there is liver fluke on-farm

Understanding the situation on your farm can help decide if animals need treatment. There is significant regional variation in the occurrence of infection. A large percentage of farms in the northwest are affected, while, at the same time, roughly 10% of farms in Ireland have not had any sign of liver fluke in animals presented for slaughter in the last five years.

The risk for each farm should be evaluated individually, although farms in some regions are clearly more at risk than others, and the history of fluke on the farm should be considered. The burden of liver fluke can be tested with faecal testing, the liver findings reported at slaughter and bulk milk tank testing. Discuss the available tests and results with your vet.

Faecal egg counts are easy to perform, but only detect eggs from adult parasites, so a negative result can’t rule out liver fluke if an animal is infected with immature flukes.

Rumen fluke are a different type of fluke parasite that rarely cause a problem in herds, unlike liver fluke, so rumen fluke eggs seen on a routine faecal test don’t usually require treatment.

Farmers whose animals have been slaughtered at a factory participating in the Beef HealthCheck programme, delivered with Meat Industry Ireland, receive reports on liver results as part of the liver and lung monitoring programme.

These reports are also available to farmers online through www.icbf.com. More information on the programme can be found on the AHI website at www.animalhealthireland.ie.

Why is the timing and product choice for fluke treatment important?

Animals in late autumn or early winter are usually infected with immature liver fluke and these can take eight to 12 weeks to develop into adults. While housed cattle can’t be reinfected with liver fluke, any parasites picked up on pastures will develop further if not treated.

Many flukicides are only effective against adult fluke parasites and therefore two treatments are often needed over the housing period, especially if the first treatment is given while the animals are still at grass or early at housing. A once-off treatment can be sufficient if:

Using a product containing triclabendazole two weeks after housing (the only active ingredient effective against early immature liver fluke). If using a product effective against late-stage immature worms after five to eight weeks in housing.If using a product only effective for mature fluke after 10 weeks in housing. Always check the product label for the targeted fluke stage. Earlier treatments may prevent production losses if the fluke burdens are high, so discuss your treatment plan with your vet.

A product targeted at immature liver fluke should be used for sheep in the autumn to early winter, as these fluke life stages can cause severe disease. There are reports of resistance to triclabendazole by liver fluke in sheep.

Therefore, these products should always be used responsibly, at the right dose and at the right time, to keep them working for as long as possible.

Liver fluke is a common parasite in Ireland and the mild, wet conditions are an ideal environment for it to thrive. Cattle infected with liver fluke are usually chronically affected, with negative outcomes in terms of growth rates, achievement of growth targets, fertility and milk yield.

A study in Irish steers showed that animals with evidence of liver fluke in the factory were lighter by an average of 36kg liveweight at a standardised slaughter age.

In sheep, migration of immature flukes to the liver can cause severe damage, resulting in sudden death. Liver fluke is also associated with Black disease, a clostridial infection, preventable through vaccination.

Liver fluke needs an intermediate host – the mud snail – to complete its life cycle. These snails live in poorly-drained, water-logged areas on the farm. If animals are infected with adult liver fluke while on pasture, the fluke eggs are released, hatch and enter the snails, where they undergo further development.

The fluke parasites leave the snails and return to the pasture, usually from late summer to autumn, as an infective stage that can then be eaten by grazing animals (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Life cycle of liver fluke.

Control of liver fluke usually involves treating effectively at housing to prevent production losses in cattle. Killing the parasites over the housing period will also reduce pasture contamination in the following spring. Prevent animals from grazing near the waterlogged areas during the high-risk period from late summer onwards. Or drain the land, if possible. If a farm is free of liver fluke, prevent the parasites from spreading to the farm with a quarantine period and treating all animals brought in before placing them on pasture. A long-term strategy is breeding cattle that are less likely to become infected with liver fluke. Sire breeding values for genetic resistance to liver fluke are now available from the ICBF. How to know if there is liver fluke on-farm

Understanding the situation on your farm can help decide if animals need treatment. There is significant regional variation in the occurrence of infection. A large percentage of farms in the northwest are affected, while, at the same time, roughly 10% of farms in Ireland have not had any sign of liver fluke in animals presented for slaughter in the last five years.

The risk for each farm should be evaluated individually, although farms in some regions are clearly more at risk than others, and the history of fluke on the farm should be considered. The burden of liver fluke can be tested with faecal testing, the liver findings reported at slaughter and bulk milk tank testing. Discuss the available tests and results with your vet.

Faecal egg counts are easy to perform, but only detect eggs from adult parasites, so a negative result can’t rule out liver fluke if an animal is infected with immature flukes.

Rumen fluke are a different type of fluke parasite that rarely cause a problem in herds, unlike liver fluke, so rumen fluke eggs seen on a routine faecal test don’t usually require treatment.

Farmers whose animals have been slaughtered at a factory participating in the Beef HealthCheck programme, delivered with Meat Industry Ireland, receive reports on liver results as part of the liver and lung monitoring programme.

These reports are also available to farmers online through www.icbf.com. More information on the programme can be found on the AHI website at www.animalhealthireland.ie.

Why is the timing and product choice for fluke treatment important?

Animals in late autumn or early winter are usually infected with immature liver fluke and these can take eight to 12 weeks to develop into adults. While housed cattle can’t be reinfected with liver fluke, any parasites picked up on pastures will develop further if not treated.

Many flukicides are only effective against adult fluke parasites and therefore two treatments are often needed over the housing period, especially if the first treatment is given while the animals are still at grass or early at housing. A once-off treatment can be sufficient if:

Using a product containing triclabendazole two weeks after housing (the only active ingredient effective against early immature liver fluke). If using a product effective against late-stage immature worms after five to eight weeks in housing.If using a product only effective for mature fluke after 10 weeks in housing. Always check the product label for the targeted fluke stage. Earlier treatments may prevent production losses if the fluke burdens are high, so discuss your treatment plan with your vet.

A product targeted at immature liver fluke should be used for sheep in the autumn to early winter, as these fluke life stages can cause severe disease. There are reports of resistance to triclabendazole by liver fluke in sheep.

Therefore, these products should always be used responsibly, at the right dose and at the right time, to keep them working for as long as possible.

SHARING OPTIONS